It was Hungary’s agricultural successes, built on the backs of laborers, like my Hungarian family members, that turned the country into an economic and cultural power.

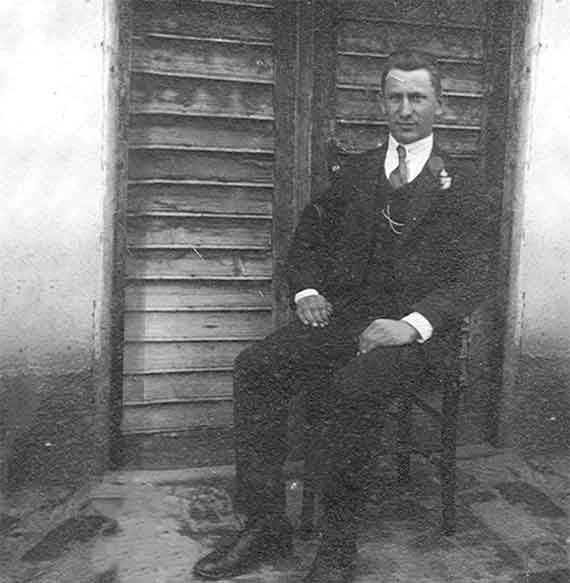

IN1902, István (25) married my great-grandmother Regina Börczi (17, from the neighboring town of Horvátkút) in this church. And soon they had a son, Pista, my grandfather, born in 1904. (Pista is short for “István,” and he is the first family member in this story that I actually knew.)

"TO THE GLORY OF GOD!"

"ERECTED BY THE WIDOW

MRS. JÓZSEF FÁBOS

AND HER CHILDREN

IN 1908"

Then József Sr. died four years later at age 62. Upon his death, his wife (my great-great-grandmother) Julianna Csizmadia (age 58) ordered an elaborate statue made from expensive stone from the north shore of Lake Balaton.

Julianna was as commanding as this statue (she ordered her young daughter-in-law, Regina, around as if she were a servant). Through the statue, Julianna let others know that the Fábos family was important.

The statue is still standing

in Marcali today, on the

main road entering town.

During this time, a new work ethic was emerging all across Europe — a new kind of thinking. Farmers across agricultural Hungary began to recognize that hard work, education, and risk-taking could bring advantages.

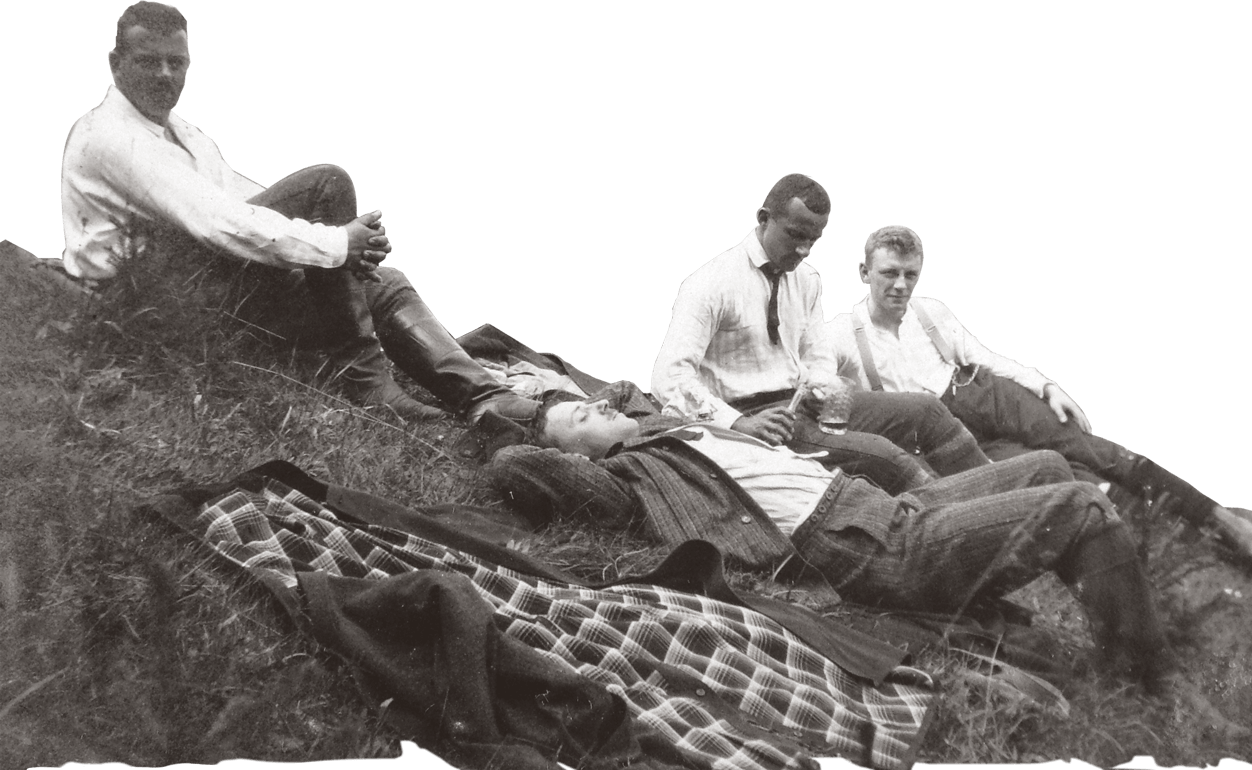

My family members were performing intense labor from dawn ‘til dusk. Young István and Regina labored in the field alongside István's parents, József and Julianna, and their other family members. Everyone evaluated one another in terms of how hard and how long they worked.

The Fábos family’s pumpkin seed oil business had somehow become successful; they were able to leave Boronka, selling their swampy land in favor of higher pastures on the outskirts of Marcali. What a move! What a step up! My father would always remember his remaining Boronka relatives as poor, with “dirty necks.”

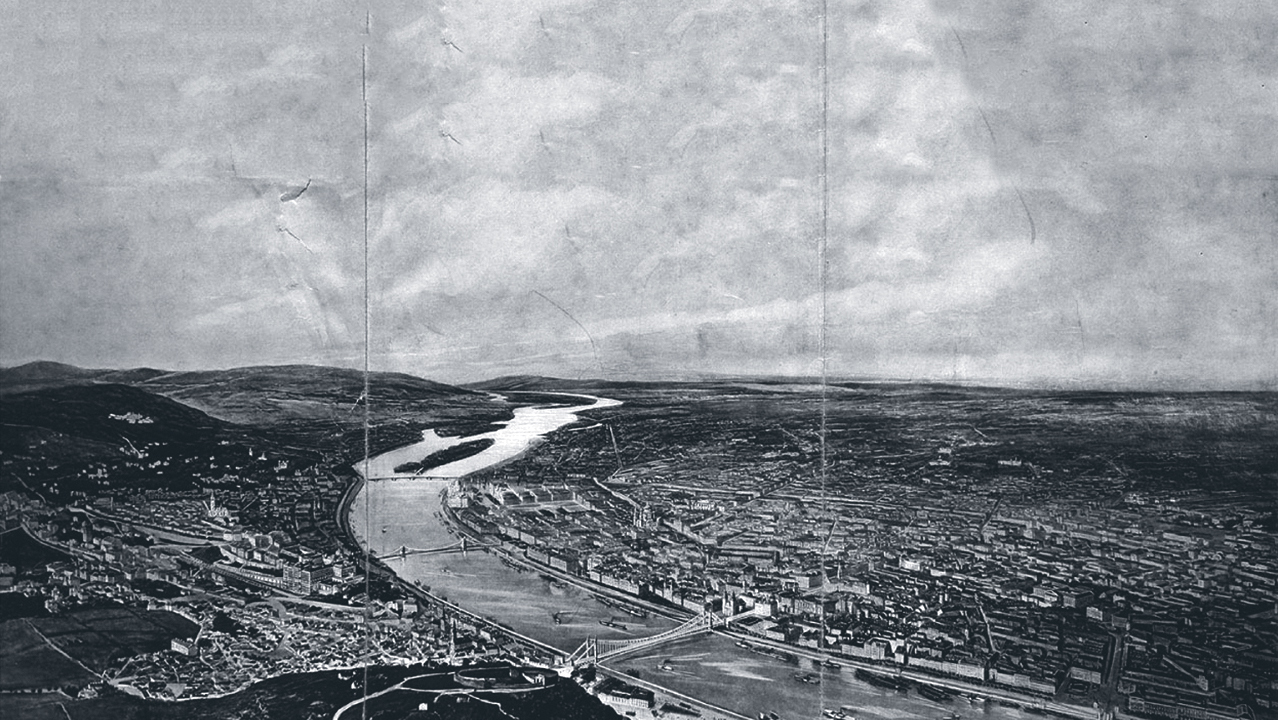

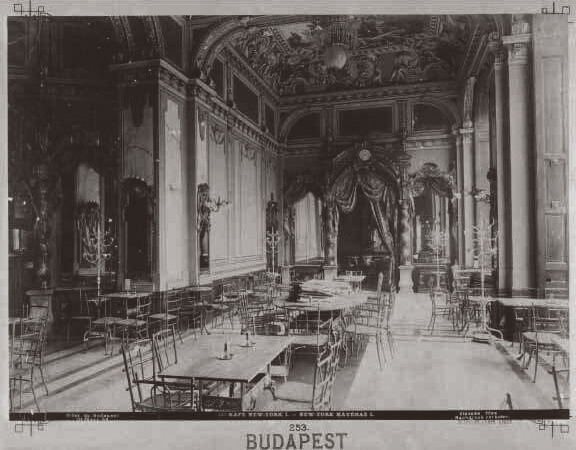

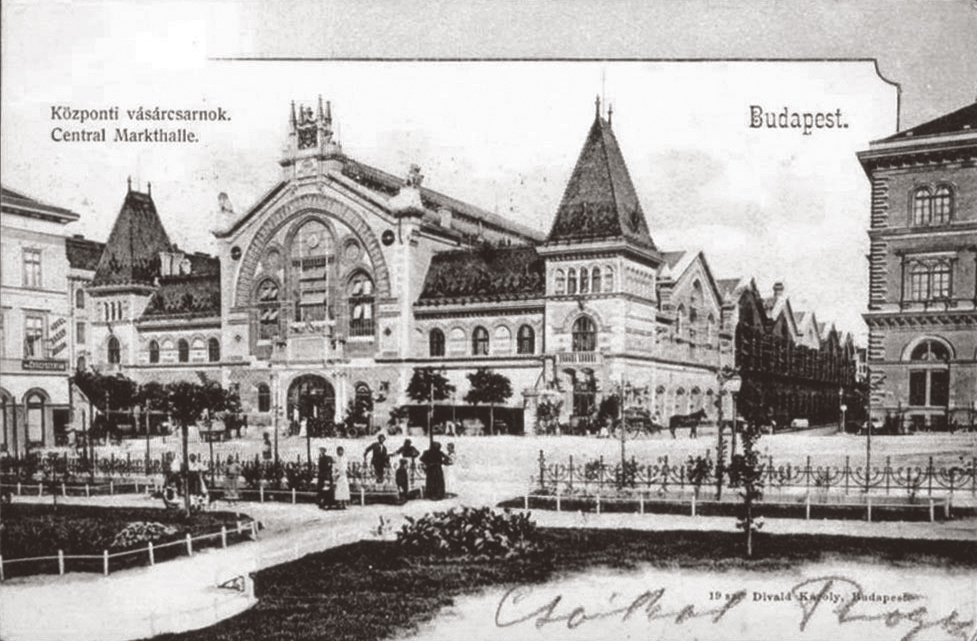

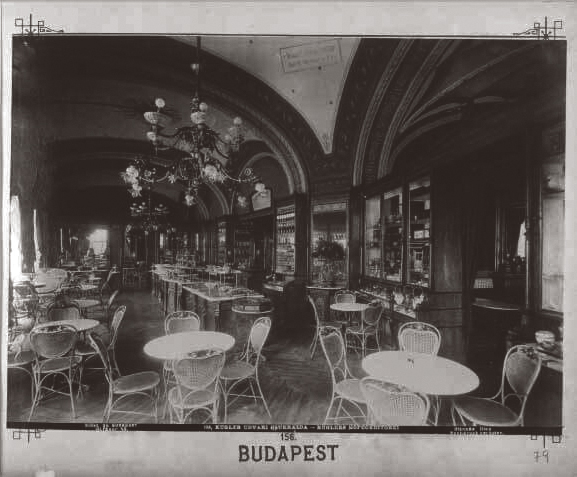

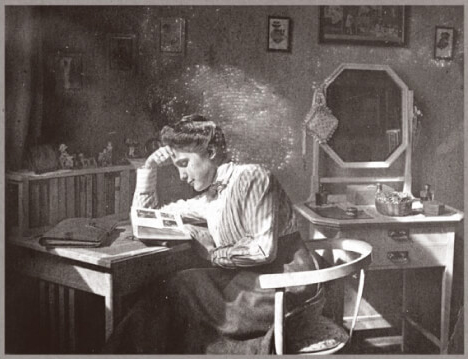

LITERACYexploded too. Thousands of periodicals and newspapers emanated from Budapest and other town centers, feeding into a robust literary and artistic scene, not to mention a vibrant café culture!

Before long, Budapest had 600 cafés, patronized by countless journalists, poets, playwrights, actors, scholars, and musicians.

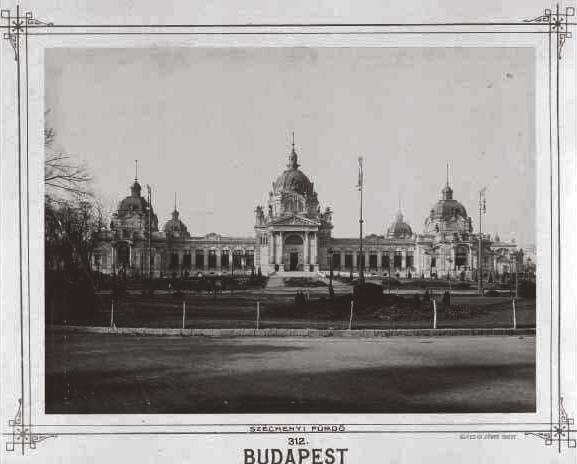

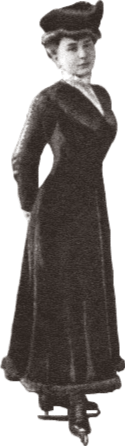

Public skating also became a favorite pastime. Budapest held the World Figure Skating Championships in 1909 — Hungary’s first world event!

What innovation!

"LONG LIVE KOSSUTH!"

"LONG LIVE OUR

NATIONAL HERO!"

A similar outpouring occurred five years earlier at the funeral of Empress Elisabeth (Sisi), a Habsburg, but also a beloved proponent of Magyar independence. She was stabbed to death by an Italian anti-Habsburg anarchist in 1889.

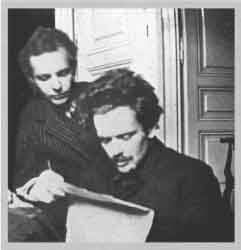

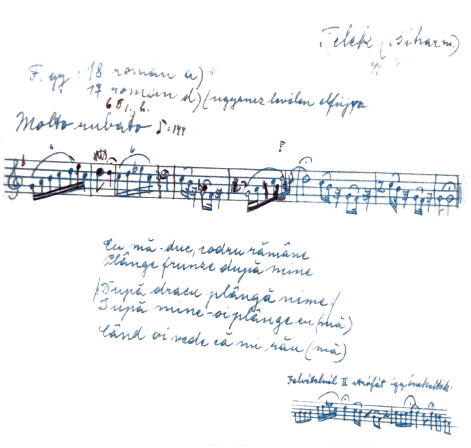

Matters of ancestry and Magyar identity had preoccupied Hungary’s aristocracy for centuries, but now a general interest in Hungarian ethnicity was flourishing. Witness composers Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály discovering “true” Hungarian folk music — which included Slavic songs, Romanian dances, and Bulgarian melodies...

Meanwhile, ethnographer/photographer István Györffy (master of the earliest color photography process, autochrome) documented the “authentic” culture of Transylvania...

... and architect Ödön Lechner developed a new “Hungarian style” that integrated folk art (and special Zsolnay ceramics) into the decorative elements of his buildings.

Only the nobility could own guns and shoot game. Only the nobility could vote or hold public positions.

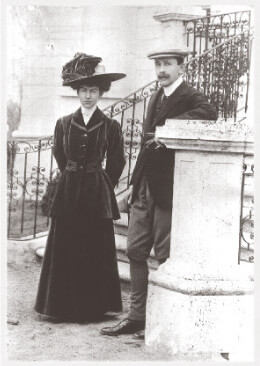

For example, László Széchényi (great-grandson to the great national hero, Ferenc), famously married the glamorous American heiress Gladys Vanderbilt in 1908. Described as having an “air of aristocratic ennui,” he proceeded to squander half his wife’s $25 million fortune.

Some Magyar nobles sold their property to afford expensive hobbies. For example, András Széchenyi, another great-grandson to Ferenc and grandson to István, was quite preoccupied with traveling to Paris on his personal dirigible airship!

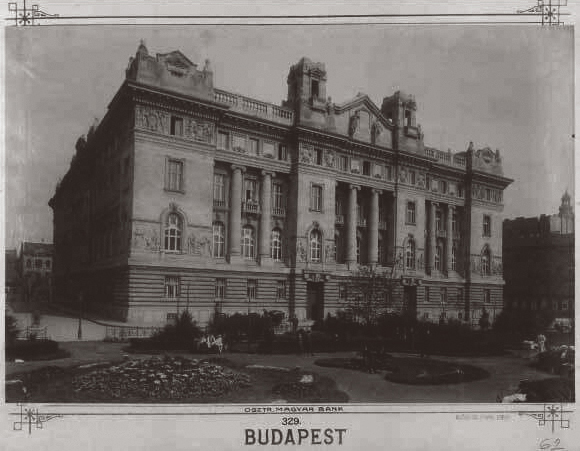

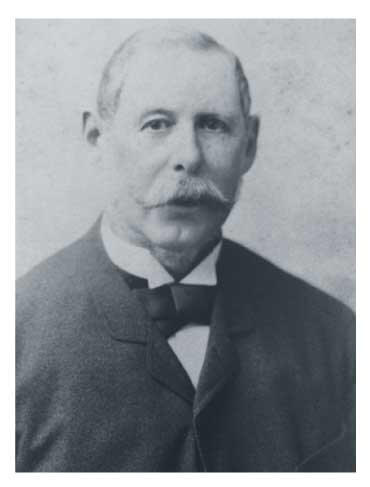

For example, Alajos Strasser, who was Jewish, was founder and president of the Hungarian Stock Exchange.

This innkeeper’s son from northern Hungary had moved to Budapest, married his niece, Fanny, formed the Strasser & König Corn Trading firm with his brother-in-law, Lévi König, and made his fortune in banking and trade. Three of his brothers (Sándor, Rudolf, and Béla) noble-ized their names to “von Strasser.” Another sister, Charlotte, married a noble-ized Jew with the fancy title of “Edmund Ödön von Goldberger de Buda.” By the 1900s, the Strasser/von Strasser family knew only fabulous wealth and extreme privilege as businessmen, doctors, and lawyers.

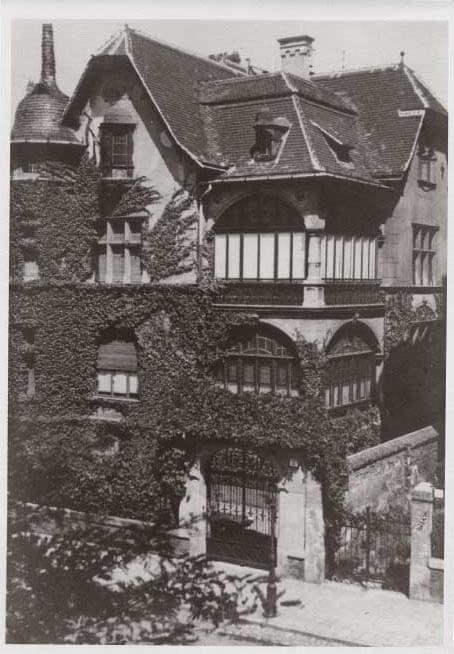

This pattern of Jewish financial and intellectual success was repeated, more or less, in smaller towns like Marcali, which had an increasingly prominent Jewish community of 374 by 1910 (about 8.3 percent of the town’s population). Ignác Mayer, a distinguished Jewish lawyer and banker in town, built the first two-story townhouse on main street, with a lavish baroque balcony.

Marcali's Henrik Marczali (born Morgenstern) was also making a name for himself as one of Hungary’s most eminent historians. The son of the town’s rabbi, Marczali had moved at age 14 to study in Budapest, then in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, London, and Oxford before returning to Budapest. Marczali would publish three volumes of the groundbreaking and monumental Magyarország Története (History of Hungary) between 1881 and 1888.

Volumes I, II, and VIII were written by Marcali’s Henrik Marczali.

Magyar-izing his name — common for Hungarian Jews — and moving in elite circles were symptomatic of this historian’s desire to assimilate and rise in social status. Marczali identified as Hungarian ethnically and Jewish only religiously, and was greatly supportive of the Dual Monarchy (having a special fondness for Habsburg Emperor Joseph II). He taught at the prestigious Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, and perhaps rode on the new electronic trolleys, which by 1900 were everywhere.

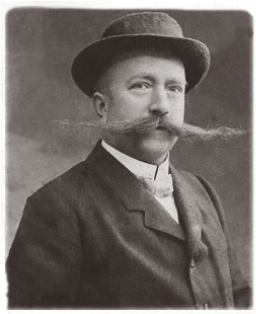

This happened in Marcali in 1901. One of the town’s most colorful figures at that time was Béla Bernáth. He was a lawyer with an enormous fondness for his pet goat. He took it everywhere, got it a special identity card, and successfully defended it in court after the goat attacked some local townswomen. Bernáth was also the first editor of the town’s new newspaper, MARCZALI, and used the newspaper to voice his anti-Semitic discomfort with the rising status of Marcali's Jews.

The first issue of MARCZALI was published in 1900 (the town’s name would formally drop the “z” in 1945). The paper came out every Sunday.

“HOW INSULTING!

I CHALLENGE YOU

TO A DUEL!”

In a scathing 1901 newspaper editorial, Bernáth wrote that Marcali’s pharmacist, Attila Rekvényi (who was Jewish), came from a “crooked country” (meaning he was foreign, and Jewish, with a crooked nose) and that “here in Marcali we need ‘straight sentences’” (meaning that Marcali’s non-Jewish “straight-nosed” intelligentsia should have more public influence).

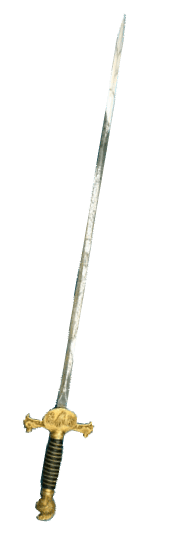

The Jewish pharmacist, Rekvényi, was on the committee to hire Marcali's new town doctor. Bernáth was firmly against hiring another Jewish doctor, and argued that Rekvényi would surely push for the Jewish guy. Rekvényi declared his public humiliation to the demeaning editorial and challenged Bernáth to a duel.

"WHERE!"

"WHEN?"

"WITH WHOM?"

Because of the many duels they were in (or could expect to be in), a large number of Hungarian Jews developed extraordinary fencing skills to protect themselves.

The duel between Rekvényi and Bernáth never happened (a bit anticlimactic), but pointed to the growing friction between successful Jewish townspeople and the Christian Magyar elite.

And as the Magyars pushed for even more Magyar power (they already controlled half the Empire) and complete Magyar autonomy, they fanned Slavic nationalism and thus made it harder for the Habsburgs to hold the Empire together.

On one hand, the Magyar nobility was pulling the country together with their intense nationalism, and on the other hand they were ripping Hungary apart with their increasing inability to accept an ethnically diverse state.

Countess Júlia “Szikra” Teleki and actresses Mari Jászai and Erzsi Paulay all addressed the crowd, including 240 delegates from 22 countries. The Congress brought attention to women’s rights, especially lobbying for suffrage. Hosting the IWC convention confirmed Budapest’s status as a cosmopolitan, modern metropolis.

The new century was thus a fabulous yet perilous time for Hungary. It was a period of social mobility for many people, including the Fábos family. But the period’s nationalism and anti-Semitism foreshadowed dark times ahead. The exuberant hopes for social progress of the early 1900s would soon be dashed by the outbreak of World War I.