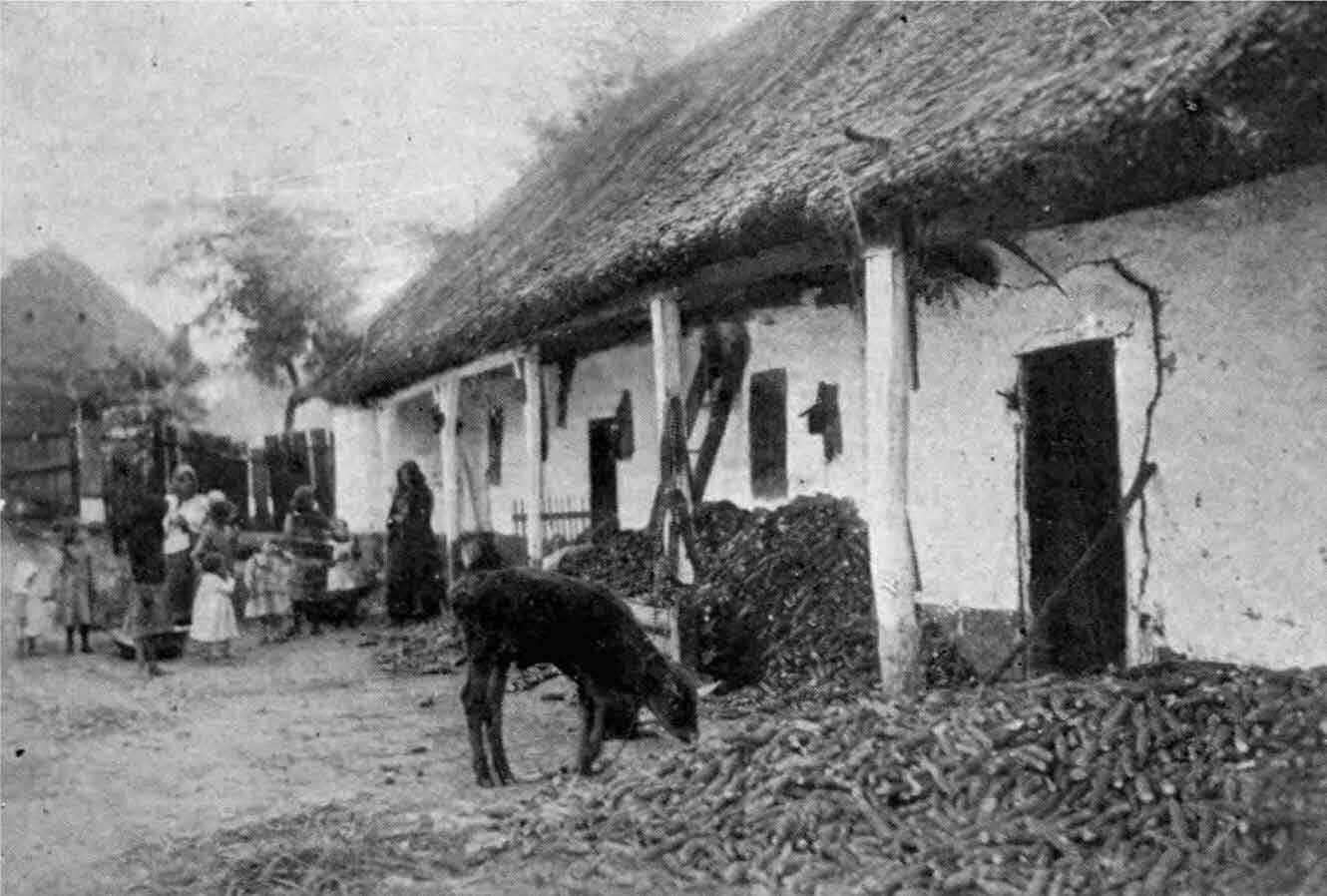

Tuberculosis was so prevalent in Hungary it was dubbed “the Hungarian Disease.”

WHENshe was three, Gizi lost her father to a brandy distilling accident. So at age nine, my grandmother was an orphan living with her aunt Mariska and her alcoholic uncle in a tiny house with dirt floors and small windows. In a short while she would be matched with my grandfather, Pista (now 14), and move to Marcali.

VILMA

dead at 29

VILMA

dead at 29

The next two years were complicated. Europe was falling apart after the war; Russia experienced the most upheaval, where the Bolsheviks overthrew Tsar Nicholas II. In Hungary, socialists, and then the more radical communists, overthrew Hungary’s nobility. But unlike Russia, Hungary’s right-wing nobility was able to regain control, literally riding in on a white horse.

First, though, Hungary had to survive the flu. As if the shell-shocked, traumatized, starving, TB-ridden post-WWI world couldn't take any more grief, the Spanish Flu raged from one country to the next, killing far more people than the Great War...

The flu's second wave, which came in October and November 1918, was so contagious and deadly that a person could come down with symptoms and die within hours.

A children's rhyme from this period went:

At the end of the First World War in July 1918, exhausted men and women could only look at their lives as if through broken mirrors. Marcali lost 246 men. Those who survived—like my forever shell-shocked great-grandfather István—came home to starving families and woebegone farms. István did not recover, and his younger teenage son, Pista (my grandfather), gradually took over the farm.

And the problems didn’t end: food shortages, labor shortages, inflation. An impulse for radical change bubbled up among vast segments of the population.

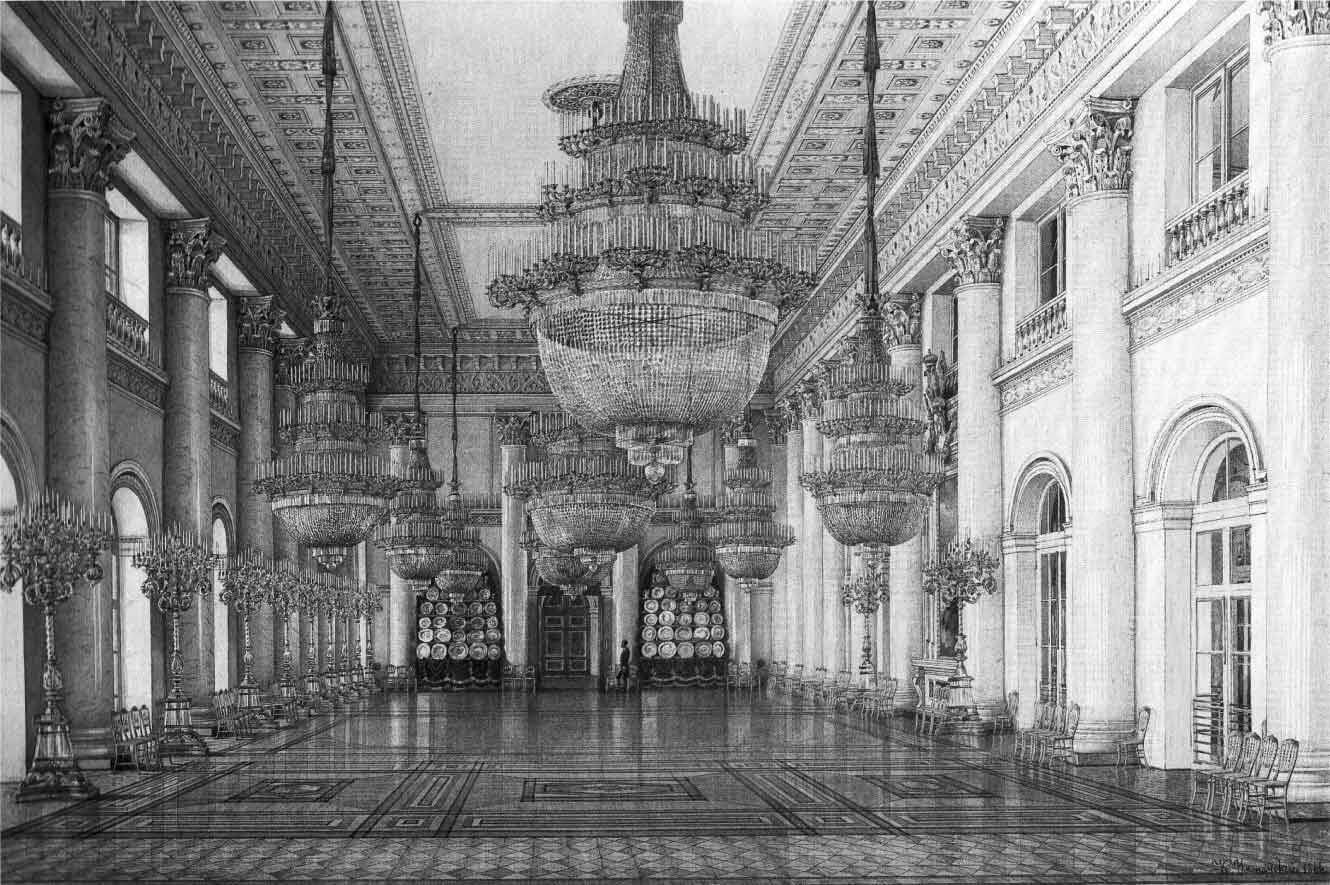

Somebody had to pay for the millions of lives lost. In central and eastern Europe, it was the great empires. The German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian Empires did not survive the end of the war. Neither did the careers (and decadent lifestyles) of their four rulers:

Tsar Nicholas II was the cousin of Germany’s emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm.

THEmost radical social changes to come out of World War I took place in Russia, where revolution broke out on International Women’s Day in March 1917. Around 90,000 women workers went on strike demanding “peace and bread,” which led to a wave of further protests and riots. Four days later, the tsar was forced to abdicate and women were granted the right to vote!

But the revolution, which started out democratic, took an extreme turn a few months later. Vladimir Lenin and other radical Marxists argued that Russia needed to go further—they needed a Proletarian Revolution.

"WE SHALL NOW

PROCEED TO CONSTRUCT

THE SOCIALIST ORDER!"

- VLADIMIR LENIN

Lenin and his followers, called Bolsheviks, quickly set about implementing their social revolution. They confiscated large landholdings and redistributed them to peasants; they let workers take control of factories; they declared equal rights for women and religious minorities.

The Bolsheviks also ruthlessly targeted their class enemies, which led to a brutal civil war in Russia that went on for several years and caused most of the Russian aristocracy to flee (some finding their way to Hollywood).

"THE TOWNS MUST BE

CLEANSED OF THIS BOURGEOIS

PUTREFACTION...

ALL WHO ARE DANGEROUS

TO THE CAUSE OF THE

REVOLUTION MUST BE

EXTERMINATED!"

- PRAVDA

(Communist Party

Newspaper)

During the civil war, the Bolsheviks realized they needed grain to feed their army and the people living in the cities. They tried to forcibly take grain away from the peasants, but the peasants cried foul, and so the Bolsheviks used propaganda to smear the moderately wealthy peasants (people they called kulaks) as “tight fisted” for not wanting to hand over their grain.

KULAK: an independent wealthy farmer emerging from the peasantry who employed labor. Direct (derogatory) translation: "tight-fisted."

"Tight-Fisted!"

"KULAK!"

"KULAK!"

"KULAK!"

"TIGHT-FISTED!"

LENINdevised a plan to get the kulaks to fall into line, the famous “Hanging Order” that he sent out to officials all over the countryside via telegram:

HANG

(AND MAKE SURE THAT

THE HANGING TAKES PLACE

IN FULL VIEW OF THE PEOPLE.)

STOP.

DO IT IN SUCH A FASHION

THAT FOR HUNDREDS

OF KILOMETERS AROUND

PEOPLE MIGHT SEE,

TREMBLE,

KNOW,

SHOUT:

NO FEWER THAN

ONE HUNDRED KNOWN

LANDLORDS, RICH MEN,

BLOODSUCKERS.

STOP.

'THEY ARE STRANGLING,

AND WILL STRANGLE TO DEATH

THE BLOODSUCKING

KULAKS!

STOP.

If you were a “kulak” farmer, you lived in terror. If you were Lenin, you lived in increasing paranoia as more and more people became disillusioned by the new social order.

Fanni Kaplan, a political revolutionary since the age of 16, was disillusioned! Two weeks after the Hanging Order, 28-year-old Kaplan reportedly shot Lenin three times with a Browning pistol after he exited a factory building where he was giving a speech. He would survive, incredibly....

"MY NAME IS FANYA KAPLAN.

TODAY I SHOT LENIN.

I DID IT ON MY OWN.

I WILL NOT SAY FROM WHOM

I OBTAINED MY REVOLVER.

I WILL GIVE NO DETAILS.

I HAD RESOLVED TO KILL

LENIN LONG AGO.

I CONSIDER HIM A TRAITOR

TO THE REVOLUTION."

- FANNI KAPLAN

Kaplan was captured, interrogated, and killed a few days later; we will never know if she was the actual shooter.

Lenin’s paranoia got even worse after the assassination attempt, and the civil war turned even more brutal. Millions of Russians died during this period from combat, political terror, and famine.

THROUGHOUTEurope and Hungary, the level of beleaguered discontent and complete social collapse was so high that emerging ideologues—promising to fix things and make life better—found welcome ears.

Obviously, the “great powers” that brought on the mass destruction of World War I had lost legitimacy in Hungary too. Over the next year, Hungary's political pendulum swung wildly, first to the left, then to the far left, then to the far right.

THEleft-wing Aster Revolution broke out in Hungary in October 1918, calling for land reform, civil liberties, and universal suffrage, which would give religious minorities the vote. The revolutionaries wore aster flowers on their lapels (these flowers bloom in October). The passionate young politician, Mihály Károlyi, was the appointed figurehead.

Károlyi came from an extremely wealthy noble family, but, like Lajos Kossuth from 1848, he favored a more democratic redistribution of land and power. He also supported women’s rights, and had a rare equal relationship (and incredible bond) with his wife, Katinka.

Katinka Andrássy was the granddaughter of the famous nobleman Gyula Andrássy (remember him from 1867? He negotiated the 1867 Compromise and wore a corset). Despite her family legacy of wealth and power, Katinka Andrássy rejected the idle lifestyles of the ruling class and, with her husband, committed herself to social welfare, political activism, and pacifism. She was president of the Hungarian Red Cross during the war. She publicly challenged the practice of recruiting village girls to army brothels. She championed a government that served all people, not just the nobility.

“THE ROLE OF

GOVERNMENT IS TO

MAKE PEOPLE HAPPIER

AND LIFE MORE

WORTH LIVING.”

-KATINKA ANDRÁSSY

Practicing the social democratic principles that he and Katinka preached, Károlyi redistributed the land of one of his estates:

"LET US REDISTRIBUTE

ALL LARGE ESTATES

(700 ACRES OR MORE)

TO LANDLESS PEASANTRY!

LET US GIVE ALL MEN

AND WOMEN

THE RIGHT TO VOTE!"

- MIHÁLY KÁROLYI

But despite Károlyi’s and Andrássy’s hopeful pacifism, their efforts provoked unrest throughout the Hungarian countryside. Impatient, disgruntled peasants burned down mansions, looted stores and granaries, and attacked land-owning priests.

KÁROLYIhad an even bigger problem on his hands, though. Although it was widely assumed that he had many friends in western Europe that would ensure a just peace for Hungary, along came the news that the Allies sought to drastically shrink Hungary’s borders. The old multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire was being replaced by nation states. This meant that the territories of Hungary where non-Hungarian speakers lived would be left outside the new borders. But even more disturbingly, so would about three million Magyars!

Hungarian anger was valid. Yes, they had fought in the war, but they certainly weren’t the main aggressors. So why were they being treated so harshly? Did Hungary’s state-building legacy in Central Europe count for nothing? How could they be a nation-state if three million Hungarians were cut off from their fatherland? How could the country support itself economically if it lost practically all of its natural resources?

Károlyi knew he could not survive such a devastating turn of events. He resigned and turned the government over to the radical left-wing political parties who resolved not to accept the new borders.

"LET THERE BE A

LENIN-LIKE

SOCIALIST ORDER!"

- BÉLA KUN

Béla Kun had been a muckraking journalist before the War. As a soldier in World War I, he was captured by the Russians on the Eastern front, learned Russian fluently as a POW, and embraced communist ideology. Then he became a “Friend of Lenin,” fought for the Bolsheviks in Russia’s Civil War, and came back to Hungary in November 1918, flush with Soviet financing, to form a Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Béla Kun (an atheist) was of Jewish ancestry, as were other prominent members of the regime. Anti-Semites used this fact to link all Jews to the idea of a Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy. This linkage would have terrible consequences, eventually, for Hungarian Jews.

ASRomania prepared to take over their share of Hungary (Hungary’s beloved eastern region called Transylvania, a mixed territory with ethnic Romanians and Hungarians), Kun promised that his Soviet Bolshevik financiers would help Hungary protect its ancient borders. Needing cash, the coalition government let Kun gain control.

Later, the Hungarian government regretted their hasty embrace of Kun. Swinging Hungary to the far left, Kun’s fledgling communist regime accomplished quite a lot in the next 133 days .... They:

COMMITTEDHungary to war against Romania and Czechoslovakia to protect Greater Hungary’s borders, now in jeopardy of being lost.

NATIONALIZEDbanks, factories, and apartment blocks.

CONVERTEDlarge and medium-sized estates into state ownership without compensation, collectivizing land instead of redistributing it to peasants.

PUTall trading, educational, and cultural institutions under state control.

REPLACEDthe police with “Red Guards.”

REPLACEDthe judicial system with “revolutionary” courts manned by laymen.

PASSEDsocial decrees in favor of women and children, giving hope, perhaps, to many of Hungary's unnamed women.

CONFISCATEDbank accounts and expensive jewelry.

CREATEDHungary’s own version of Lenin’s Red Terror, led by a gang of scary, leather-clad men who called themselves “Lenin Boys.”

For factory workers, disillusioned soldiers, and the poorest peasants, Béla Kun's radical socialist rhetoric may have made some sense. For the wealthy elite who were attacked and killed by the "Lenin Boys" and forced to nationalize their businesses, they were justifiably scared. For sure, the aspiring, land-owning Fábos family were no fans of Béla Kun’s schemes for Soviet-style collective farming!

The Kun government invaded Czechoslovakia to inspire a Bolshevik revolution there as well. Meanwhile, the Romanian army, with the blessing of the western allies, invaded Hungary and advanced as far as Budapest, pillaging, requisitioning, and dismantling factories to the last screw along the way. The Soviet Union, preoccupied with their own civil war, never did lend a hand to Hungary.

ANDsoon Hungary’s political pendulum swung wildly again! In southern Hungary, a far-right, counterrevolutionary militia had organized to take down Béla Kun and his "Lenin Boys.” After Romania’s invasion, they worked with the Allied powers to negotiate a Romanian retreat in mid-November 1919 and simultaneously take control of Hungary (Kun, in the meantime, had fled to Vienna). At the helm of this far-right militia was Admiral Miklós Horthy.

Horthy had been an assistant to Emperor Franz Joseph, so he was an “old school” conservative allied with the aristocracy and the now-dissolved Habsburg Empire. He had been a naval officer. He was a nationalist. He opposed women’s rights. He was anti-communist and anti-Semitic (these two were now fused).

He stood for everything the short-lived Károlyi and Kun governments did not.

Horthy's group now attached themselves to the myth of heroic Magyar warriors and Hungary's claim to the entire Carpathian Basin. Many Hungarians remember Horthy today as “honorably withstanding the Romanians” near Lake Balaton (not far from my family’s farm) to claim the mantle of Hungarian nationalism.

Horthy was named Regent (almost a king), and became the symbol of conservative, Christian, traditional (some might even say backward or reactionary) Hungary for the next 20 years.