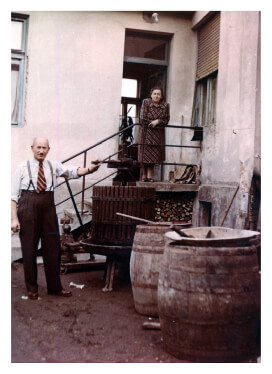

THEstate required my grandparents to split their house in two and share the nicer half with a Communist Party member’s family, who stayed there whenever they vacationed on the Balaton.

THERákosi regime had successfully turned Hungary into a “country of iron and steel,” but in the process, Hungarians’ quality of life had plummeted.

They were now wearing mismatched shoes, created by untrained workers on chaotic shoe factory assembly lines at Hungary’s single, massive, Danube Shoe Company. The state-run company had separated right and left feet assembly lines to streamline, and thus increase, production.

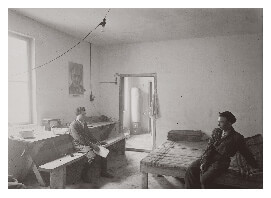

They were living in shoddy buildings that were missing essential features like window seals, insulation, and proper lighting fixtures. Many of these buildings, like the school Gyula had helped construct, had flimsy, three-centimeter-thick floors and terrible ventilation. These buildings were built on productivity quotas; like so many parts of the Hungarian economy, quality was the lowest priority.

They were standing in endless lines with ration tickets in hand, hoping to buy a brick of lard or some flour to make bread, often coming home with nothing except feelings of anger.

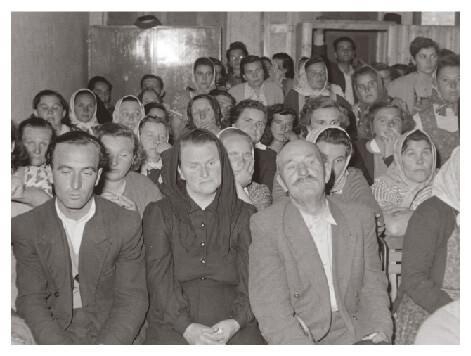

MEANWHILEmany agricultural workers were now assigned to vast, collectivized, modern farm complexes planting a hundred acres at a time. These were bleak places, void of children in the farmyard (they were at "young pioneer" camps), or grandfathers watering the flowers (flowers were not part of the economic plan).

Perhaps the worst part of totalitarian Hungary in the 1950s was the way every social relationship was compromised. Authorities considered any meeting of more than two people suspicious. Therefore, trusted acquaintances wavered and then turned the other way. Friends stuck to discussing nothing but the weather. Parents became terrified of their own children, who might report them if they revealed their private beliefs, and resorted to whispering under the bed covers.

Meanwhile, Hungarians had to publicly fake euphoria—about this new social order, about the industrial turn, about the communist regime—all the while despising and questioning all or much of it.

By 1956, many supporters of communism, who had thought a radical new society would improve their material conditions, were disillusioned.

Women, who had faced extreme hostility in the new communist workforce, felt doubly betrayed: they were at the bottom of every post on the communist ladder.

Those who doubted all along (and often faced consequences for that doubt) were harboring an increasingly explosive anger.

From 1948 to 1956, Hungarians had protested individually. They walked off their jobs, did their assigned work as minimally as possible, exaggerated production levels, diluted their milk—all to protect themselves in some way. In the process, their exhaustion from poverty and extreme political repression had hampered their will to openly protest. They were just figuring out how to survive.

But when Rákosi and his gang regained power in 1955, ending Imre Nagy’s “New Course,” public resentment against the regime boiled.

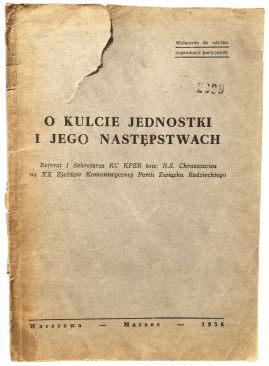

March

ANDwhen the Soviet Communist Party’s new leader, Nikita Khruschchev, gave a shocking “secret speech” that exposed and denounced Stalin’s ruthless purges, Hungarians suddenly felt more free to criticize Stalin and Soviet policies, too.

“STALIN SHOWED IN

A WHOLE SERIES OF CASES

HIS INTOLERANCE,

HIS BRUTALITY

AND HIS ABUSE OF POWER...

HE ORIGINATED THE CONCEPT

'ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE...'”

NIKITA KRUSCHEV,

SECRET SPEECH

Throughout the next months, Hungarians in Budapest, and in towns like Marcali, began to openly express their discontent and share terrifying stories of their experiences (there were so many of them). Like the one about what happened to Mr. Gelencsér. He owned a little bar in Marcali close to the Fábos farm, and when Marcali’s ÁVH searched his shop and found a hidden jar of sugar cubes, they sentenced him to two years of hard labor for “intentionally depriving starving, working class people of sugar.”

July

THEPolitburo forced Rákosi to resign. Again! It was a reprise of 1953. But they made an enormous miscalculation. Instead of reinstating Imre Nagy as they did in 1953–the softer, gentler communist, and the person most Hungarians preferred to lead their nation—the Politburo installed another hardliner from Rákosi’s inner circle: Ernő Gerő.

October 23

Day 1

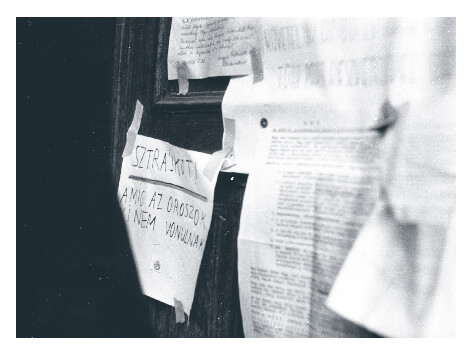

ONTuesday, October 23, 1956, the revolution started in Hungary’s capital city as a peaceful, hopeful student march from Buda to Pest. Students circulated a list of sixteen demands, which included:

- The evacuation of all Soviet troops

- General elections

- A new government led by Imre Nagy

- Trials for Mátyás Rákosi and his accomplices

- A new political, economic, and cultural relationship with the Soviet Union

- A reorganized economy steered by knowledgeable specialists

- A living wage

- Fair treatment of independent farmers

- The release of political prisoners and other innocent victims

- A free press

- Party member elections (at every level) by secret ballot

- The dismantling of Budapest’s large Stalin statue (a symbol of Stalinist tyranny and oppression) near Heroes’ Square

The students posted these demands in doorways and on every tree along Budapest’s main boulevards. Small knots of people gathered to read them, and crowds began to mill in the streets. Budapest was in motion.

INthe meantime, 200,000 Hungarians gathered by the Parliament building chanting:

“RUSSIANS, GO HOME!

RUSSIANS, GO HOME!”

“IMRE NAGY!

WE WANT IMRE NAGY!”

IMRE NAGY:

“DEAR COMRADES...”

CROWD:

“WE ARE NOT

COMRADES ANYMORE!”

By 9 p.m., a nervous Imre Nagy finally arrived on the balcony. He was not good at winging things, and immediately annoyed the crowd by using grating communist jargon and telling the protesters, not the Russians, to go home. In the end he awkwardly sang the Hungarian National Anthem.

Instead of disbanding, part of the crowd marched to Radio Budapest and demanded the station broadcast the students’ sixteen demands. ÁVH officers opened fire on the crowd.

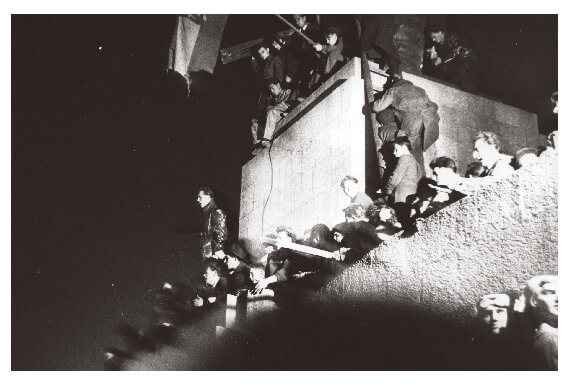

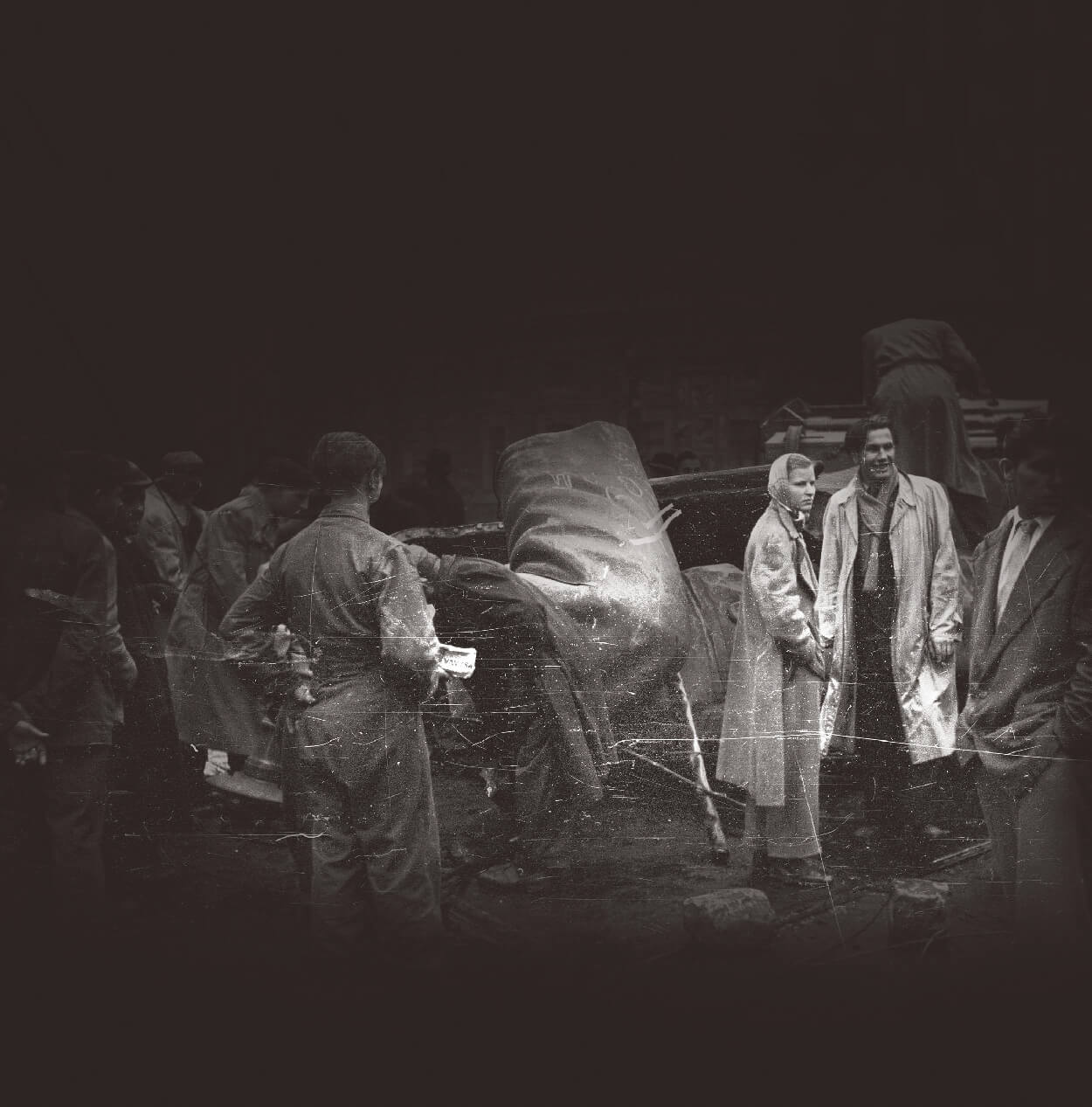

MEANWHILEanother crowd toppled the Stalin statue near Heroes’ Square and dragged it down Andrássy Street (then Sztálin Street), Budapest’s main avenue.

Protesters seized guns from military depots, distributed them to newly organized militias, and set fire to police cars.

Others openly vandalized any symbol of the Communist regime.

“WHAT IS HAPPENING”

“WHAT DID YOU SEE?”

The “freedom fighters” drove through the night, carrying national flags and shouting revolutionary slogans.

“DOWN WITH GERȌ!”

“RUSSIANS GO HOME!”

October 24

Day 2

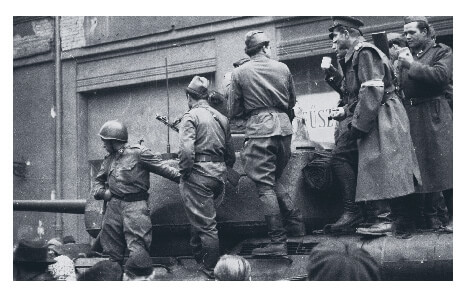

ONthis second day of the revolution, thousands of Hungarians in Budapest and across Hungary had organized into militias to battle the ÁVH, pro-Soviet communists, and Soviet troops.

Throughout the countryside, revolutionary councils aggressively removed Communist red stars and Soviet war memorials. They rounded up ÁVH officers and burned communist files and records.

By 2 p.m., October 24, six thousand Soviet troops reached Budapest. The army tanks poured in.

Approximately 15,000 revolutionaries took up arms in Budapest. These were mostly young workers—angry, brave, and dedicated—who felt they had nothing to lose. They were deeply nationalist, anti-Soviet, and anti-Russian, but they were not antisocialist. Their average age was 25, and they wore “revolutionary” ribbons to identify themselves.

“WE WANT IMRE NAGY!”

“DOWN WITH GERO!”

“RUSSIANS GO HOME!”

“WHERE IS MY RIBBON?”

October 25

Day 3

THEmost horrible massacre of the revolution happened on the third day. A crowd of about 10,000 people had assembled in front of the Parliament building, and guards protecting the Parliament couldn’t figure out the loyalty of the tanks entering the square…Soviet? Hungarian Army?... Then indiscriminate shooting began, perhaps by the ÁVH sharpshooters on the rooftops. In the end, 60-80 protesters were killed and 100-150 were injured.

Meanwhile, thousands of people were losing their lives in Debrecen, Győr, Sopron, and other cities throughout Hungary.

And yet, the revolutionaries were surprisingly effective against the Soviet army. The Communist government collapsed and Imre Nagy became Prime Minister. This is what many Hungarians wanted.

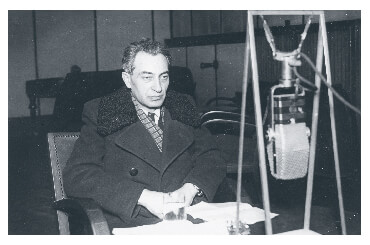

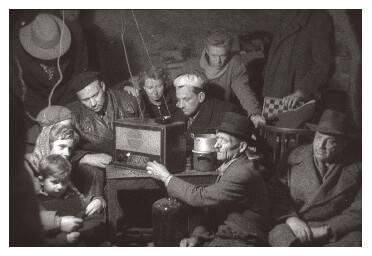

But the U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe (RFE) was not satisfied with Nagy. Broadcasting night and day from Munich to 500,000 radios around Hungary, RFE mouthed shrill, uninformed, and anti-Communist propaganda that incessantly pressed insurgents to abolish, rather than reform, the communist system.

“DO NOT TRUST IMRE NAGY!

VIGOROUSLY PRESS AHEAD

WITH ALL YOUR DEMANDS!

OVERTHROW THE NAGY GOVERMENT!”

- RADIO FREE EUROPE

BYthe sixth day, Nagy had arranged a ceasefire and negotiated talks between the insurgents and the Soviet government. Soviet troops withdrew to the Hungarian countryside. People ventured outside to examine the devastation.

October 30

1956

Then Nagy announced, on the radio, the formation of a multiparty system and declared an end to the secret police. Cardinal Mindszenty, among other political prisoners, was released from prison.

“In the interest of

the further democratization

of the country’s life,

the cabinet abolishes

the one-party system

and puts the country’s

government on the basis

of the democratic cooperation

between the coalition

parties as they

existed in 1945….”

- imre nagy

October 31

Day 7

INCREDIBLY,the Soviet government announced in Pravda that it would begin a total withdrawal from Hungary. The statement created a worldwide sensation. Was this really happening?

But that night, Khruschchev couldn’t sleep. He was troubled by the lynching. Troubled by Nagy’s announcement of a multiparty system. Troubled by a hunch that Nagy was too wimpy to maintain order. Troubled by the imperialist West, which was sure to gloat at a Soviet withdrawal.

He decided to reverse the order and not withdraw troops. He decided to do the opposite: invade Hungary with a massive show of strength.

AT DAWN,the Politburo told Nagy of Khrushchev’s reversal. Nagy spent a day making appeals: to Western leaders, to ambassadors of the Warsaw Pact, to the Soviet leadership (who ignored his calls).

Hungarians had no idea that an enormous Soviet army was now mobilizing by the Soviet-Hungarian border and preparing to invade their country. For three days they lived in complete, ignorant bliss. The Revolution was successful! Shops opened with food and a few trams in the capital were able to function. People went back to work and marveled at the free press that had sprung up overnight.

November 4

Day 11

NAGYkept the impending invasion from his people to prevent panic. It started early in the morning on November 4, as hundreds of Soviet tanks encircled Budapest and randomly shot at buildings while air strikes came from above.

And then immediately afterwards, thousands of Hungarian participants were rounded up. Arrested. Tortured. Hundreds executed. Imre Nagy was captured.

There were five-o’clock curfews and Soviet checkpoints everywhere. A young boy was shot simply for running.