Epilogue

ASchildren in this photograph in 1939, Ari and Gyula couldn’t have imagined their lives would turn out this way. They loved each other, loved their family, and loved their life on the farm. Yet, in the next two decades their own country would plunge them into a horrible war; exterminate their Jewish neighbors; arrest, torture, and imprison Gyula and his father; push the family off of their land; and tear sister and brother apart. What happens when your own country does this to you?

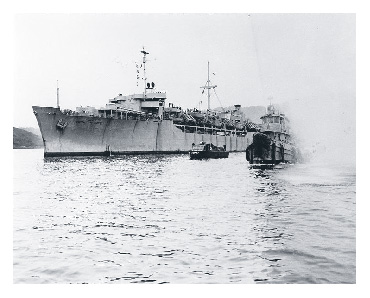

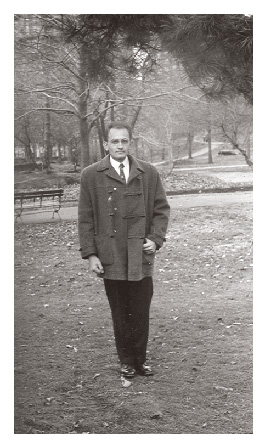

GYULAescaped to Vienna. Months later he gained passage, as a refugee, on the General Le Roy Eltinge, a U.S. Navy transport ship, to the United States.

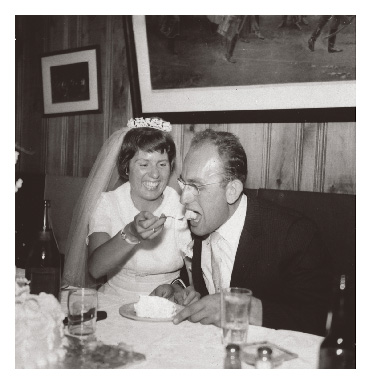

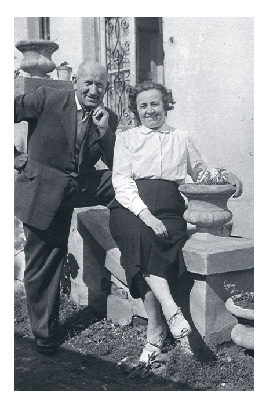

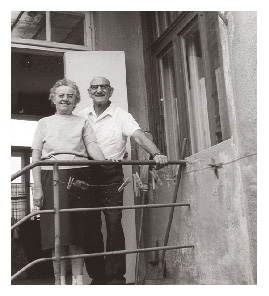

He continued his studies in agronomy at Rutgers in New Jersey and married a Swiss kindergarten teacher named Edith Haüsermann in 1959. Later on, Gyula went to Harvard to study landscape architecture and became a professor of landscape planning in Amherst, Massachusetts.

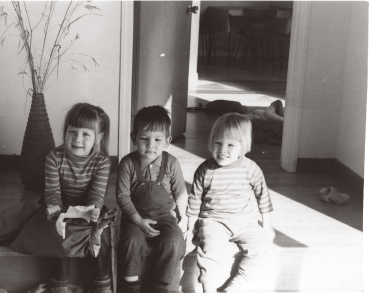

Gyula and Edith had three children: Anita, Adrian, and Bettina. I am the “youngest,” a twin, born five minutes after my brother in 1965.

ARI,though she remained in Hungary, moved farther away from the family’s roots by marrying László Hévizi, a Budapest-trained lawyer and chess champion.

Pista and Gizi could not relate to László’s big city ways or formal education. László knew nothing about farm life.

According to family lore, he criticized Gizi’s salad dressing (it may have just been a misunderstanding), making his relationship with Ari’s parents grow so strained that he rarely went with Ari to visit Keszthely.

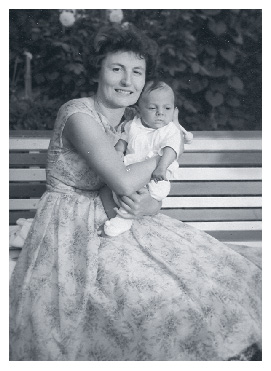

Ari and László had a son, László Hévizi, Jr., known as Laci.

They lived a modest life in a small apartment on Hungária Körút, one of the commercial thoroughfares encircling Budapest. They learned to survive the post-’56 communist system.

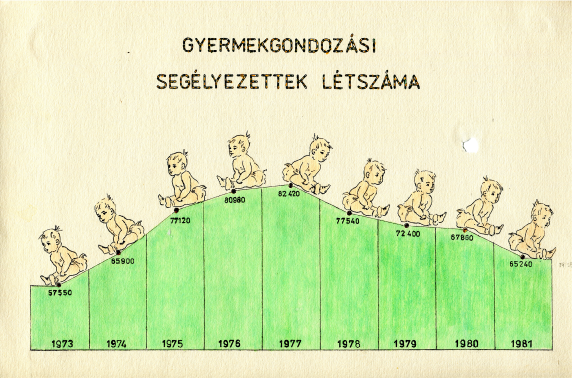

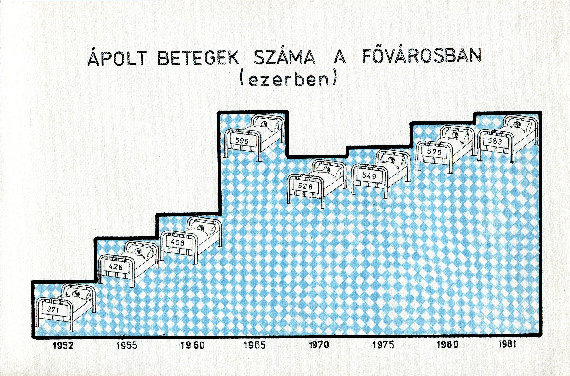

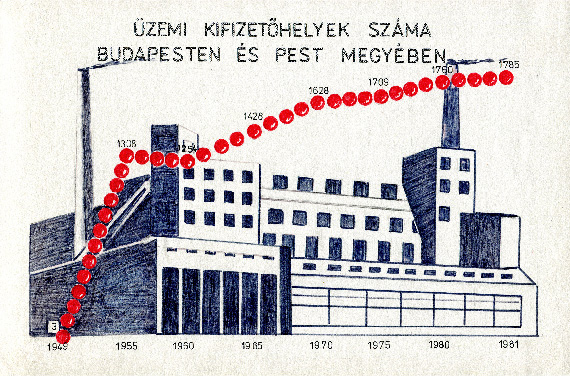

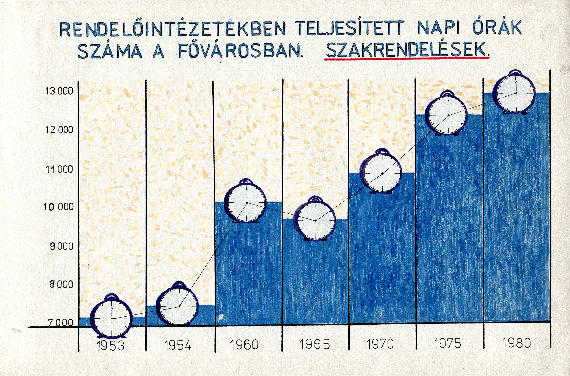

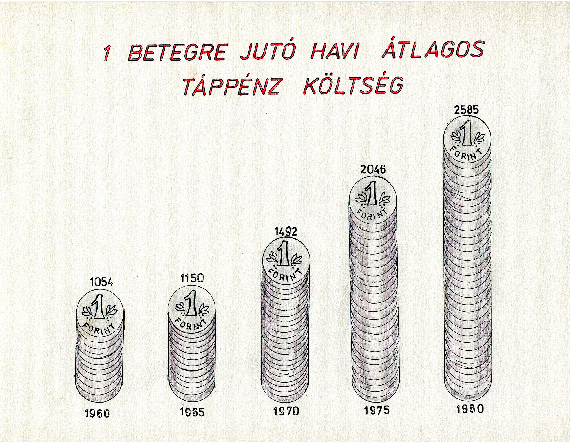

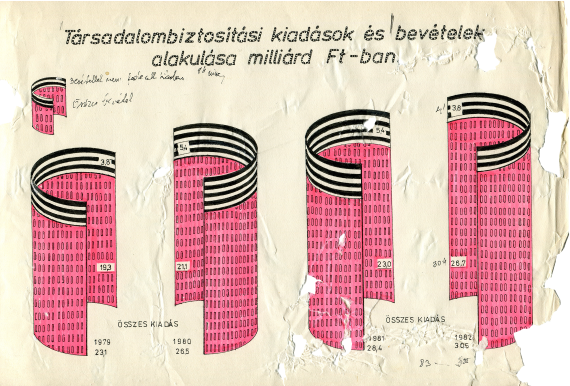

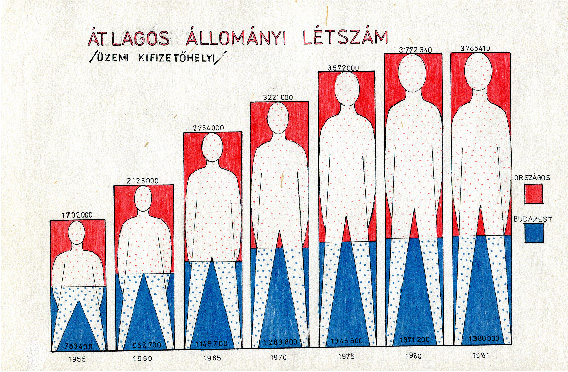

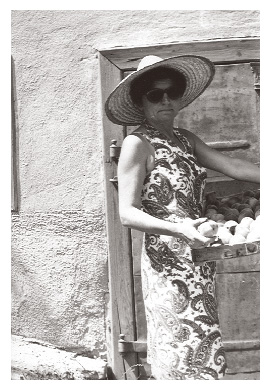

And after ten years working as a statistician, Ari finally became an artist! In 1966, the state health insurance company needed someone to promote the progress of universal health care, and it turned out that she excelled at data visualization.

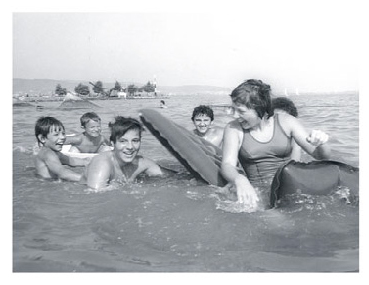

Ari and young Laci visited Lake Balaton as often as possible as a reprieve from the busy city. One enduring luxury in communist Hungary was an abundance of time.

PISTAwas arrested by Soviet-backed authorities a year after Gyula’s escape in 1956. He was sentenced to six months hard labor in Tököl, south of Budapest—punished, it became apparent, for his son’s participation in the revolution and subsequent escape from Hungary.

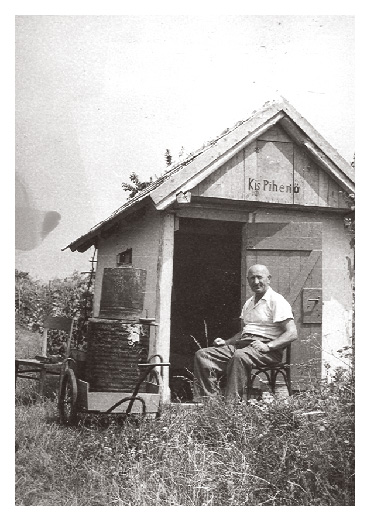

Pista survived the camp and came home to his job as a postal worker. He maintained two tiny vineyard plots, one in Marcali, the other near Keszthely. He made excellent wine, which he privately sold in his backyard.

GIZIstruggled to acclimate to the new system. She lost her son to America, her husband to forced labor, and her daughter to Budapest.

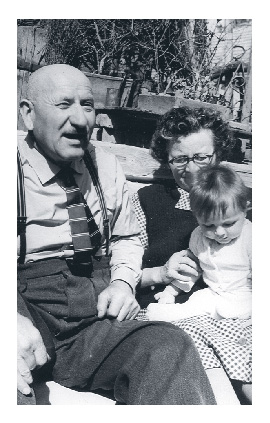

In the 1960s, she had thrombosis (a clot in her vein) and was not quite the same anymore, becoming ever more dependent on Pista and deteriorating mentally and physically. For Gizi, adapting to life off the farm was next to impossible.

Returning Home

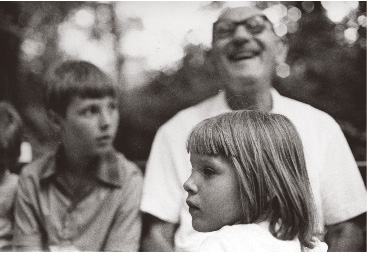

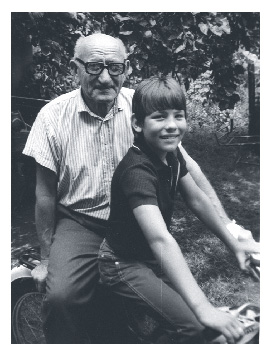

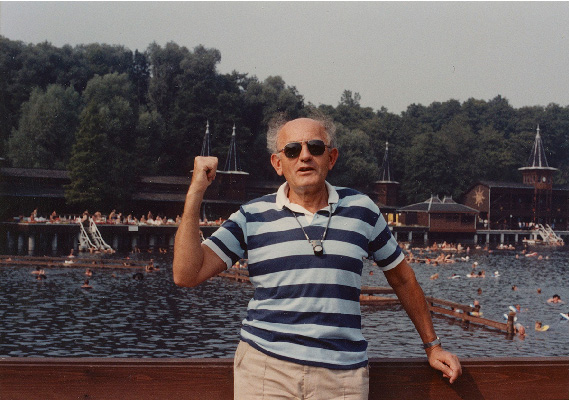

FOURTEENyears after the ‘56 Revolution, Hungary was a much different place. The political terror of the 1950s gave way to a more relaxed “Gulyás” Communism and my family began to visit Hungary every two to three years. My siblings and I adored our grandfather Pista. He taught us how to crack a whip and drive a moped. Though he could sometimes be domineering and had a temper, he could communicate with us even though we could only speak a few phrases of Hungarian.

I never knew, until my sister and I interviewed Ari in 2005, that she had wanted to escape with Gyula to Vienna and beyond. I like to imagine what would have happened to Ari if she, too, had found her way to America.

Ari stayed because Hungarian women were meant to do as they were told, were meant to take care of their parents. As a boy and then a man, Gyula never experienced these kinds of limitations.

On the other hand, it was not Gyula’s choice to leave Hungary and create a new life in America. Recalling his time at the state agronomy school in the years after World War II, he imagined a full life in front of him as the inheritor of a large farm:

Land

ALTHOUGHliving a new life in America, Gyula still could not imagine life without land. The communists had taken his patriarchal inheritance, but much of Gyula’s identity now came from acquiring properties in America.

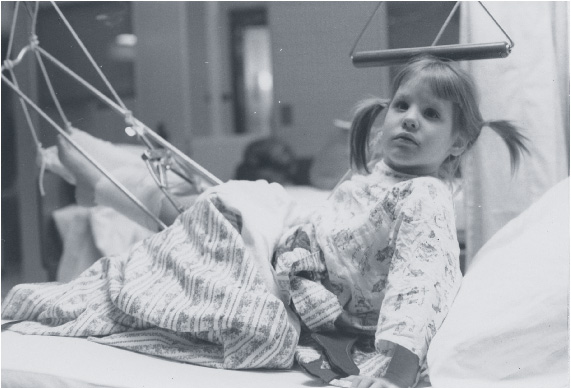

As soon as my parents settled in Massachusetts, Gyula bought a duplex house at the end of a dead-end street that came with five acres of forest. A few years later, after I was hit by a car (age five), my father used the insurance money to buy another eighteen acres nearby.

Soon after, Gyula and his wife Edith went into a partnership with a developer and purchased two apartment complexes, each on 2-3 acres, in western Massachusetts. Edith was tasked with the bookkeeping. My sister, brother, and I did the weeding. It was a lot of work and everybody hated it, with the exception, maybe, of Gyula.

In 1991, Gyula purchased a final 90 acres of forest in rural Massachusetts and his mission was complete: he had amassed the same acreage of land that communist authorities had taken from him. His desire, it later became evident, was to pass this land on to his only son. As with Ari, my sister and I were meant to marry well, while our brother was meant to carry on the patriarchal tradition of landholding. It caused a rift in my own family, proud and torn.

Coda

MYfamily's history mirrors many of the successes and defeats in the national narrative, especially when it comes to land. They received land after the 1848 Revolution. They farmed it well enough to expand their property, taking advantage of Hungary’s growing economic position at the end of the 19th century. They benefited from Horthy’s economic policies during the interwar years that prioritized Magyars. They saw their land turned into a WWII battlefield. And they became victims of the communist takeover, ultimately losing their holdings. Their identity and pride were associated with land, and their lives went into substantial upheaval when their land was torn away.

The Hungarian narrative about land stretches back all the way to 895, when the valiant Magyar men on white horses supposedly claimed the rights to the Carpathian Basin and created an empire. The narrative consistently involves patriarchy, ownership, and expanding borders.

But, beneath the surface, there are other stories that should be told: the stories about how people make a country, not just its borders. The stories about those who were never placed on mythical white horses: women, peasants, and an eclectic mix of ethnicities—Jews, Serbians, Slovenians, Ruthenians, Romanians, Slovaks, Germans, Roma, and others. This story is about rural as much as urban; about women as much as men; about Ari as much as Gyula. It's about how all of these people tried to survive Hungarian history.