Downtown Marcali also supported a growing number of merchants, craftsmen, lawyers, journalists, and tradesmen, who made up the middle class.

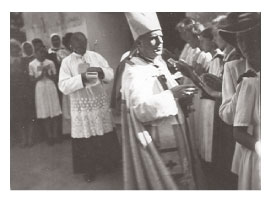

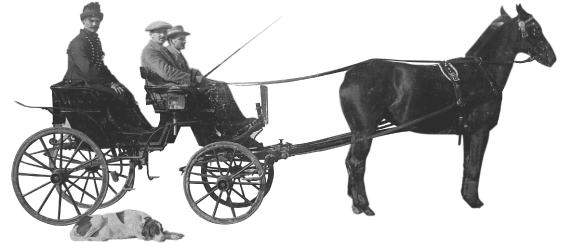

There were a few people of nobility: one aristocratic family in particular, the Széchényi family, lived in a castle in the center of town.

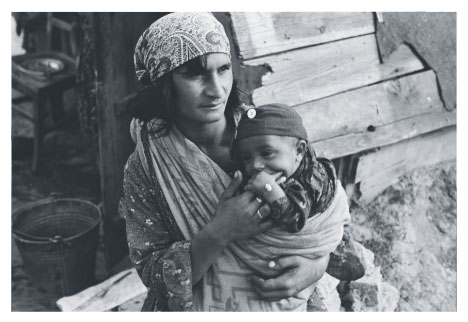

And like many Hungarian towns, there was a community of disenfranchised Roma (some call them Gypsies) living on the outskirts.

Hungarians pronounce the “s” (as in “Fábos”) as a shhh. To make it sound like an “s” in the English language, they put a z after the s, as in “Széchényi” [SAY-CHAIN-YEE]

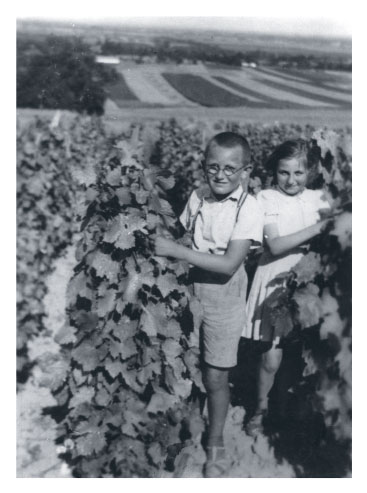

Ari and Gyula’s family—my family, the Fábos (FAH-BŌSH) family—was right in the middle: in the middle class, in the middle of Hungary, in the middle of Europe, and in the middle of some of the most catastrophic years in Hungary’s (and Europe’s) history. They suffered, not as much as some, and much more than others.

By the time Ari and Gyula were in grade school, the Fábos family had achieved middle class prosperity. Their father, Pista, bought a fancy German camera and documented life on the farm, providing a glimpse of rural Hungary in the twentieth century.

Today these photos are my window into this far-off Hungarian world. I am American—my father, Gyula, left Hungary in 1956. I grew up looking at these photos and wondering what his and Ari's lives were really like.

Most histories of Hungary focus only on the nation’s “great men,” emphasizing high politics, aristocrats, and the view from Budapest. But there is so much more to the story! Agricultural workers, small-town residents, women, and other forgotten individuals, like my family members, all lived and made Hungarian history.

This story begins centuries before there even was a place called Hungary and ends in 1956, when the lives of Ari and Gyula, these two siblings and best friends, these two lovely people who became my aunt and my father, were sent in drastically different directions.