One-ninth of János’s crop went to Pál Széchényi and one-tenth of his earnings went to the church. He was obligated to give hours of free labor to Széchényi during plowing and harvesting seasons. And he had to pay imperial taxes, which supported the Habsburg Empire, not Somogy County where he lived. To work extra hard would have been foolish.

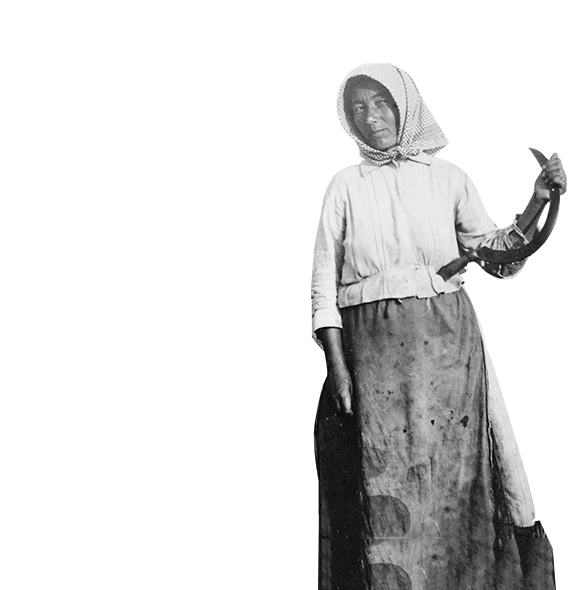

Meanwhile, Juliána struggled to manage the extra animals, the children (some of whom would have died at young ages due to pneumonia, smallpox, and the like), sew clothes according to prescribed colors and materials, and cook meals in a house with no chimney. Confined to a “soot house,” Juliána was likely, very frequently, covered in soot.

Juliána and János periodically starved or just got by. They would never get ahead, unless — according to superstition — they had a seventh child who could lead them to hidden treasure. One of their sons, József — my great-great grandfather — was born in 1846. They may have had other sons or daughters ... I will never know!

What I do know is that their lives were like their parents’ lives, whose lives were like the generations before them, over many centuries. The difficulties of this sooty, starving existence cannot be overstated. Many peasants — possibly János and Juliána — lived in an alcoholic haze.

The most socially superior families in and around Marcali were the local nobles: the Széchényis, Hunyadis, and Festeticses, who all tended to intermarry and controlled (with the clergy) the land in the region. Along with the 140,000 or so other noble families throughout Hungary at the time, the Marcali nobility still enjoyed the extreme privileges brought by the 1221 Golden Bull. They paid no taxes. They (and only they) could vote, or hunt, or carry out justice. They also received hours upon hours of free labor from their serfs. The whole system was rigged in the nobility’s favor.

And yet ... some Hungarians had been seeing this division between the privileged and non-privileged as increasingly unhealthy for the country for some time. A few thousand tremendously wealthy noble families controlled millions of impoverished peasants, some of whom rented land they weren’t allowed to leave, while others worked as serfs on manorial estates. Indeed, the desire for reform had been brewing for decades, not only in Hungary, but all across Europe.

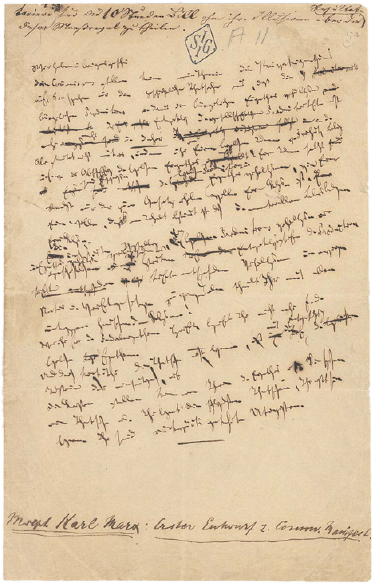

ITwas no coincidence that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who had met in 1844 in a French café (friends for life!), were beginning to formulate a set of ideas that would become The Communist Manifesto. Published in 1848, the first sentence gets to the main point:

"THE HISTORY OF

ALL HITHERTO

EXISTING SOCIETY

IS THE HISTORY

OF CLASS STRUGGLES.”

Marx and Engels, who wrote about the new industrial proletariat and capitalistic exploitation in factories, would in turn influence others throughout Europe — including agricultural Hungary — where social change seemed increasingly necessary.

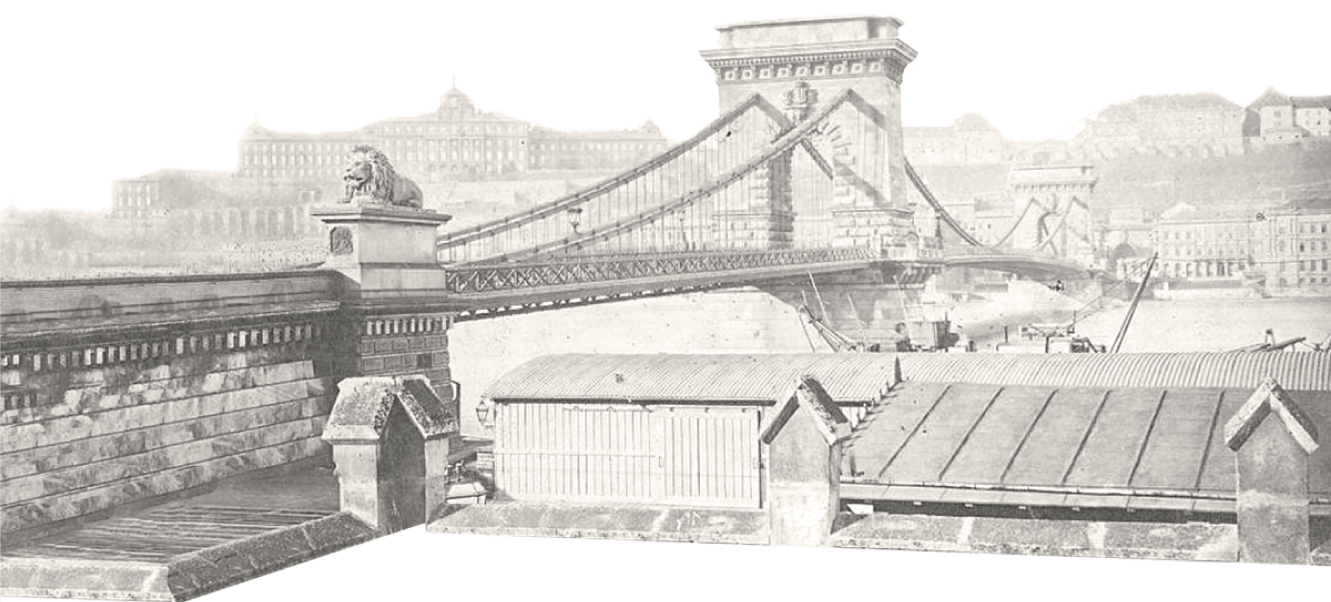

ISTVÁN SZÉCHENYIHe came from an esteemed noble family and could trace his ancestry back to Prince Árpád. He was proudly nationalist and wanted to beautify Buda and Pest and create national institutions. He was literally a bridge builder (having spearheaded the magnificent chain bridge project linking Buda to Pest) and an “old school” reformist who wanted to work within the system and continue ties with the Habsburgs.

István Széchenyi believed loyalty to the Habsburgs would lead to stability and prosperity. But he also worried that Hungary would not modernize. His extended family also owned much of the land around Marcali, where my family labored.

“I FEEL PROFOUND PAIN

AND DOWNHEARTEDNESS

AT THE SITUATION...

OF OUR COUNTRY....

OUR COUNTRY IS SLEEPING.”

- ISTVÁN SZÉCHENYI

István Széchenyi questioned the nobility’s inalienable rights to land, making him unpopular among his peers, but not as unpopular as the fellow in the other camp.

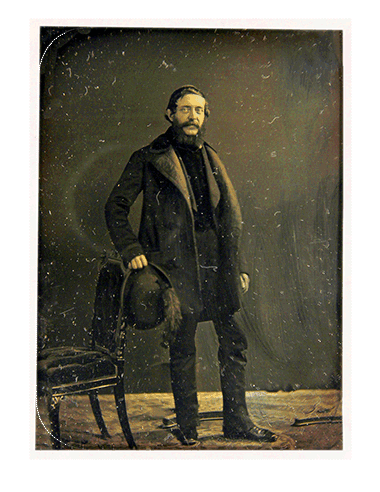

LAJOS KOSSUTHHe was the son of a landless lesser nobleman and editor of the progressive paper Pesti Hírlap. Like Széchenyi, Kossuth believed in ending the extreme privileges of the landed gentry, freeing the serfs, and ending all public floggings. However, he wanted more. Having been influenced by new ideas of liberalism, democracy, and nationalism, Kossuth wrote dazzling editorials that pushed for complete Magyar autonomy from the Habsburg Empire and for economic prosperity through education, democratization, and culture.

“I WILL LABOR FOR FREEDOM

AND FOR THE MORAL

WELL-BEING OF MAN!”

- LAJOS KOSSUTH

Pesti Hírlap, means Pest News. Pest was its own city before becoming part of Budapest in 1873.

It’s not often mentioned that Széchenyi was raised speaking German (like most noble elites) and had to learn how to give speeches in Hungarian. Kossuth grew up speaking HUNGARIAN; his rhetorical eloquence went unquestioned (he also had handsome facial hair that men all over Hungary would imitate). Kossuth’s ideas were winning favor. As Széchenyi would once say to Kossuth:

“FOR GOD’S SAKE

DON’T USE THE NIMBUS

OF YOUR POPULARITY

TO PLUNGE US INTO CHAOS!”

- ISTVÁN SZÉCHENYI

Revolts in Vienna successfully caused the Emperor’s much-despised chancellor, Prince Klemens Von Metternich (responsible for many inequitable Habsburg policies), to resign and flee to London.

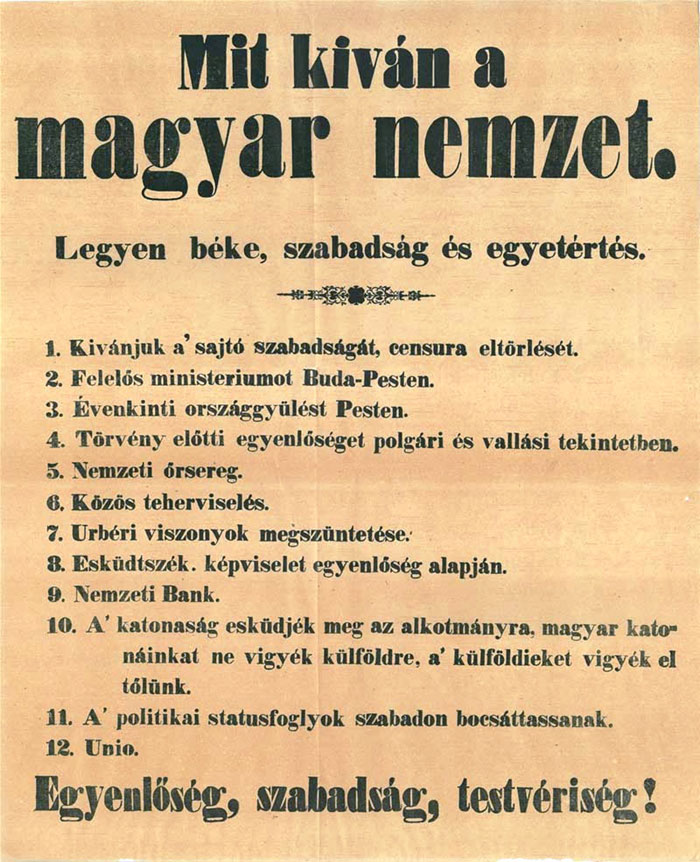

... and the Imperial Governor accepted all of the demonstrators’ demands. The revolutionaries formed a new government, sanctioned by Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand himself.

The problem with this new democracy, however, was that it wasn’t very democratic. The Magyar nationalists (nearly all members of the nobility) neglected to set chairs out for peasant representatives — the ostensible beneficiaries of their reforms. Also not included were all the people who lived in Hungary but did not consider themselves to be Magyars: the Croatians in the south, for example, or the Romanians of Transylvania. Both the Croatian and Romanian nationalists protested their exclusion from the new government. Just like so many other instances in Hungary’s history, in 1848 class and ethnic divisions prevented the country from truly unifying.

Franz Joseph's favorite pastime was sketching and drawing. He also had a fondness for military outfits and worshipped his mother, Sophie, who was likely his main advisor.

1849

Imperial armies would trounce every revolution across Europe that year.

István Széchenyi wound up in a mental institution. He killed himself in 1860, but his name rings today in Hungarians’ ears as another VIP Magyar hero.

There was one enormously positive outcome to this year-long revolution that directly concerned my peasant family ancestors. The Habsburgs emancipated peasants across the Austrian Empire. It was tactical: if Emperor Franz Joseph was to maintain control, he needed to satisfy the peasants’ basic grievances and thereby neutralize the largest segment of the population. So, with the stroke of a Habsburg pen, land — mostly forests, swamps, and about 280,000 acres of actual farmland — was given to peasants for free.

Not every peasant got land. Those who had previously worked on a manorial farm (about one-fifth of all peasants) were “emancipated” with no property. They often had no choice but to resume life as before under serf-like conditions on those same farms. Their misery continued.

But some peasants (and my family was in this group!) received land parcels large enough to conceivably farm. Conceivably is the important word here: only 280,000 acres of prime farm land were reassigned from the Magyar noblemen (who were compensated handsomely). Some peasants received parcels of forest, clay, or wetland.

1853

19.17 acres amounts to about 7.75 hectares.

The official measurement was 13.5 hold, the standard unit of land measurement in Hungary after 1851.

1861

“IT IS BETTER TO ABOLISH

SERFDOM FROM ABOVE

THAN TO WAIT FOR

THE TIME WHEN

IT WILL BEGIN TO ABOLISH

ITSELF FROM BELOW”

- TSAR ALEXANDER II

And Hungary — despite ongoing abject poverty for many, and a sublimely wealthy aristocracy — was becoming a slightly more equitable place.