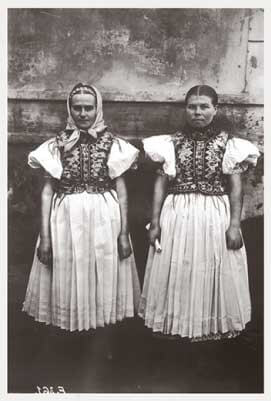

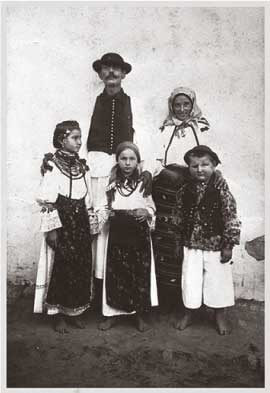

COLLECTIVELY,they were freed of 12,373,000 days of harvest labor and 11,717,000 days of compulsory plowing per year. With their free time, Hungarian peasants created a robust folk culture that included sumptuous embroidery, delightful felt appliqués, and intricately painted eggs.

Larger than the inferior sickle, scythes sped up harvests.

Manure and nitrogen fertilizers led to higher crop yields, especially in western Hungary (where, remember, my family was farming in a swamp).

Farmers began to rotate wheat, barley, and other traditional crops with legumes, clover, and alfalfa so as to preserve and also enrich the soil. The practice made the fields more productive!

With sturdier steel plows, the amount of land plowed in a day increased from about seven to almost ten acres.

Steel plows, like the prized Sack plow from Germany, increased the chances of digging up real gold and silver coins from the Roman era. This development spurred a boom of "seers" and "lookers," who touted their treasure-finding services.

Coming from Switzerland, these cattle produced prodigious quantities of milk. Recall that in Marcali, nobleman Pál Széchényi had already procured these beautiful cattle before the 1850s. He was ahead of his time!

Keeping livestock in stables and feeding them a combination of clover, alfalfa, and turnips (produced by crop rotation) meant that peasants could house their animals through the winter, avoiding the practice of killing them at the end of every year.

New railway systems enabled the transport of perishable items (like fresh milk from the Simmenthal cows) to market centers like Buda, Pest, and Zagreb.

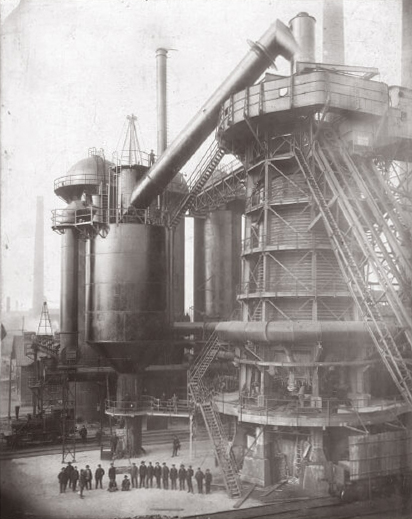

These new machines accelerated wheat processing. Hungary was number one in European flour production, producing premium flour from the country’s steely wheat.

Compulsory military service took young farmers like my great-great grandfather József Fábos to various areas throughout the monarchy and introduced them to all these successful new farming techniques, which they then brought home with them.

In Hungary’s agricultural revolution, farmers weren’t all the same anymore. There was an entire new social hierarchy of people who worked the land:

received a full lot after the 1848 Revolution and had prospered through improved farming techniques. They rented their horses and plows to “smallholder” peasants, and quickly rose in status, building bigger farmhouses (with chimneys!).

Houses with chimneys!

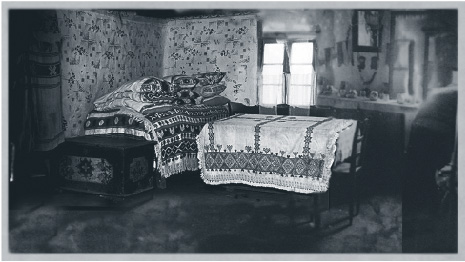

A new feature of these middle class houses was a "tiszta szoba" (clean room). The room was almost never used, but served to prove that a family could build a bigger space than they actually needed and could display embroidered linens that did not risk being spoiled by kitchen soot.

tiszta szoba

The best seats in church were reserved for the larger landholders, and their children were the inevitable kings and queens of the wine festival.

“BETTER LET THE LANDOWNER’S SON WIN…”

with smaller lots had less status (and smaller houses) and needed to exchange their labor to hire a horse and plow.

were less advantaged than the smallholders. They had to leave their homes six months out of every year to work the manorial fields and sleep in sheep barns. Still, they earned an income and had their scraps of land (and shreds of dignity) to return to when the harvest season was over.

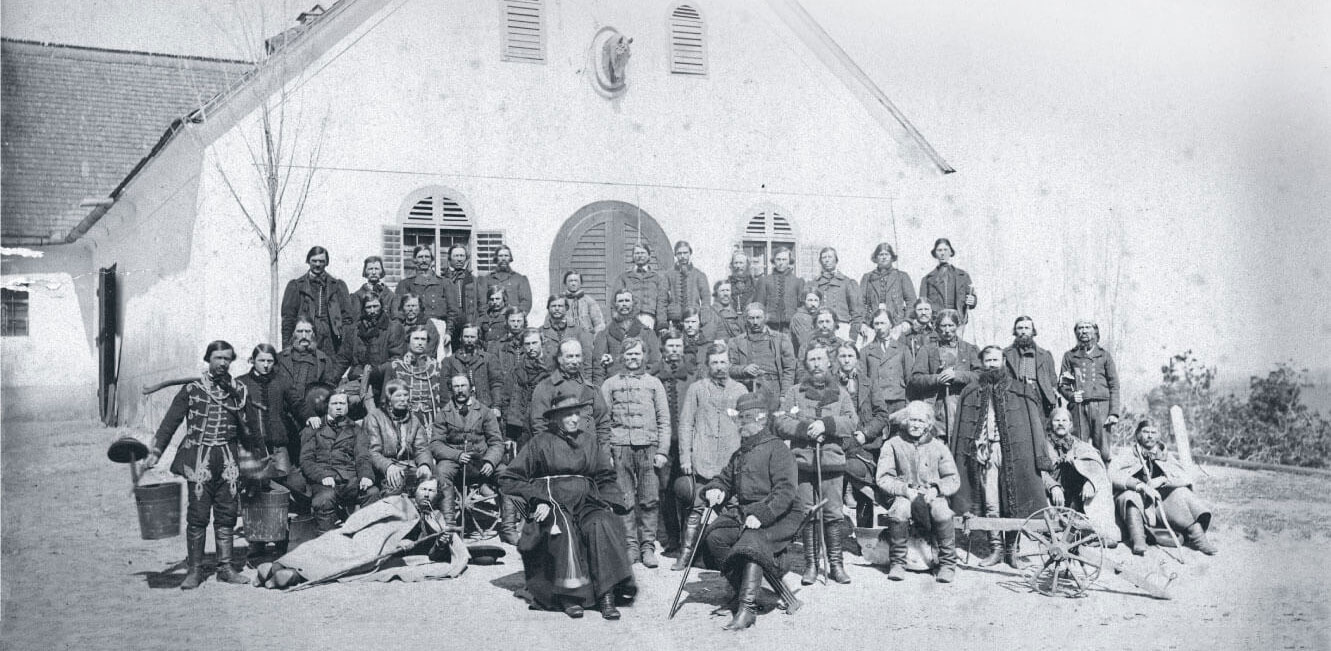

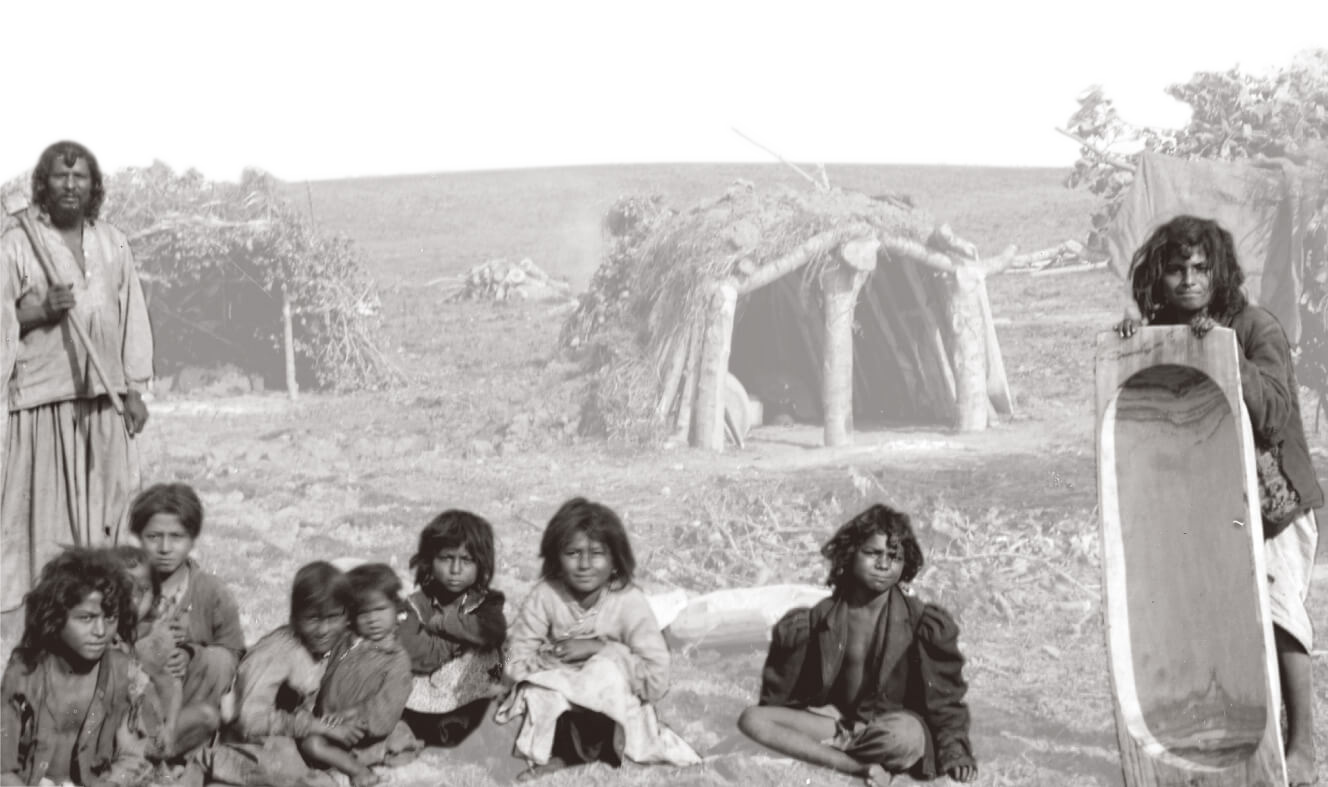

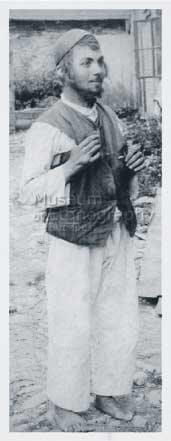

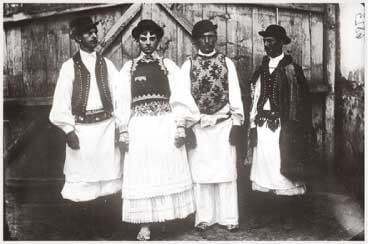

labored (and lived) on manorial estates and were the lowest of all agricultural workers. Isolated, landless, with barely any chance for advancement, they were forever stigmatized as lazy, stupid farmhands. This photograph, taken in 1867, captures the social hierarchy on a manorial estate in Tolna County, not far from Marcali.

Highest in the pecking order, the Chief Steward managed the entire farm and reported to the noble landowner.

A local Catholic monk, this clergyman was a landowner through the Church, and also had high status.

The coachmen, vinedresser, cattle herd, shepherd, miller, gardener, and the senior farm hands had tough lives, but they had bearable living quarters and some means for economic betterment. The shepherd, for example, could keep 20 percent of the lambs he looked after and a share of the curd. None of these first tier workers, however, owned any land.

The field workers were the unhappiest lot of all. They lived with their families in wretched hovels with damp dirt floors — four families to a room. Tuberculosis was rampant and people regularly attacked each other with scythes. If their children reached ten years old, maybe they would survive. Field workers could leave the farm once a year for the town fair, and were no better off than serfs.

The nobility would often have multiple residences, and would drop in on their castle(s) now and then, between stays in Budapest and opulent trips across Europe.

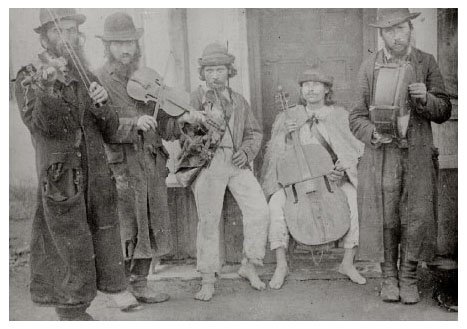

The Roma were on the other extreme, at the very bottom of the social ladder. As non-landowning folk who traveled in caravans, they were treated with derision in the local farming community. And yet, they worked a range of unique and important jobs, such as music entertainment, tinkering, and woodcarving.

Any new landowner lived with uncertainty. If they had crop failure — perhaps cheated with a rotten batch of fertilizer — they fell into debt and easily lost their land, facing again the squalor and unhappiness of a manorial farm, and marginalized forever as stubborn and inept.

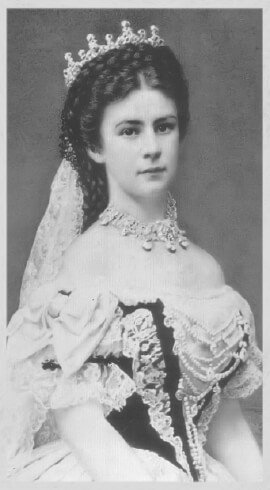

EMPERORFranz Joseph had been ruling for almost 20 years. He was now married to the gorgeous and emotionally volatile Duchess Elisabeth of Bavaria, who seemed allergic to Vienna and also to the Emperor. Meanwhile, Franz Joseph had to contend with a wily, dissatisfied, and vocal Magyar nobility, who were unhappy with the outcome of 1848 and were still occasionally demanding Magyar independence from the Austrian Empire.

Magyar noblemen were fiercely proud of the story of their nearly 1000-year old Hungarian history (what with Prince Árpád, Kings Stephen and Matthias Corvinus, Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II, the Széchényi noblemen, Lajos Kossuth, and all that). They had begun to wear their elaborate “díszmagyar” costumes to every public event to make a visual statement about Magyar pride and nationalism.

MAGYAR NOBILITY IN THEIR FANCY DÍSZMAGYARS

“Dísz” means ornament in Hungarian.

The Magyar noblemen's nationalist cause drew the sympathy of Empress Elisabeth ("Sisi"). She had rejected Vienna and fallen for Hungary, for Hungarians, and perhaps for the Magyar statesman Count Gyula Andrássy, one of the most ardent supporters of Magyar autonomy within the Empire.

Gyula Andrássy wore a corset to keep himself slim.

On behalf of the Hungarians and Andrássy, Sisi played a key role in negotiating the Hungarian Compromise of 1867, becoming a rare example of a female Hungarian national hero. She said to her Emperor husband:

“IF YOU SAY ‘NO’

[TO MAGYAR AUTONOMY]

THEN...YOU WILL BE RELIEVED

FOREVER FROM MY FUTURE.”

- SISI

Franz Joseph said “yes!” Incredibly, Hungary was made an equal partner of Austria within the Habsburg Empire, and Andrássy, upon Sisi’s insistence, was made Hungary’s first Prime Minister.

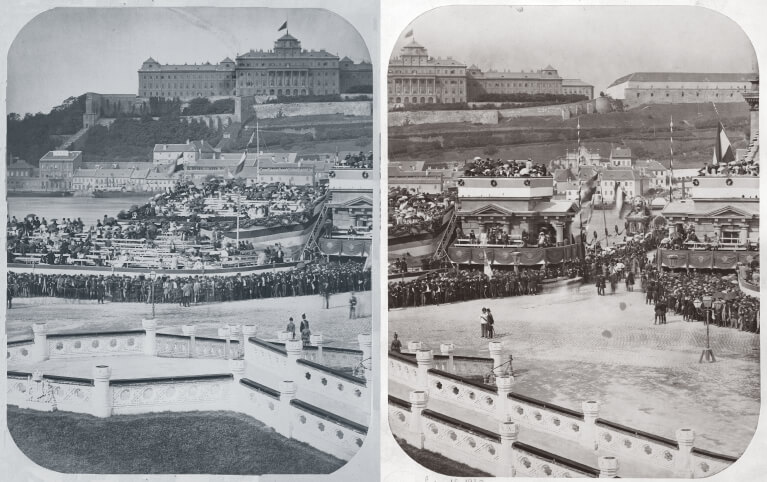

THEREwas a lavish, over-the-top coronation in Budapest to celebrate the new Dual Monarchy in January, 1867. Dignitaries gathered at the foot of István Széchenyi’s famous Chain Bridge on a mound made up of dirt from every part of the country.

For all this, Empress Sisi allowed Franz Joseph one more night with her, and exactly ten months after the coronation she gave birth to their fourth and final child ...

The Compromise was an incredible deal for the Magyars, who made up only nineteen percent of the Dual Empire, and maybe for Jews, who finally became imperial subjects. But it wasn’t so great for anyone else in Hungary because it elevated Magyars over all other ethnicities in the Kingdom of Hungary. With their newfound power, the Magyar nobility waged a campaign to deprive and destabilize the other ethnic minorities within the Kingdom, curtailing, for example, Slovak, Romanian, and Serbian languages in schools and public institutions.

“THE SLAVS ARE NOT FIT

TO GOVERN;

THEY MUST BE RULED”

- GYULA ANDRÁSSY

SENSING this rise in Magyar hubris and nationalism, the many other nationalities within Hungary became more nationalist themselves. This would become evident in their newly conspicuous folk costumes, dutifully recorded (and even encouraged) by turn-of-the-century ethnographers.

The last two decades of the 19th century were marked by rising ethnic tension, risky farming ventures, and millions of Hungarians of various ethnicities emigrating to America. They sent their surplus wages home, and the lucky could buy land upon their return.

Hungarian immigration to the United States would peak in the early 1900s.

A number of noble families also left the countryside at this time – either they failed in the more competitive farming economy, or cashed out and settled in cities like Budapest (Buda merged with Pest in 1873) to engage in newly prestigious banking and bureaucratic occupations.

As for my peasant ancestors, young József Fábos and Julianna Csizmadia had a son, István Fábos (my great-grandfather), in 1877. This Magyar Catholic family successfully farmed pumpkins, and even started a pumpkin seed oil business.