BYthis time, five years into the war, much of Europe had already been torn to pieces and reimagined according to Nazi desires for a European empire. So far Hungary itself (including the beautiful capital of Budapest) had been more or less spared.

And perhaps it would remain so.... Hungarian leaders had been desperately trying to disassociate from Germany. For every one of Hitler’s demands, Horthy’s Prime Minister Miklós Kállay, appointed in 1942, had played dumb, delayed, and withheld information (this made Hitler furious), while secretly colluding with the Allies and trying to prevent a Soviet invasion.

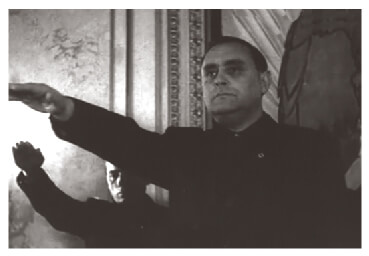

But by March, 1944, Hitler had had enough. He strategically invited Horthy to Austria, and then made his German army take over Hungary, depose Kállay, and replace him with the acceptably anti-Semitic Döme Sztójay as Prime Minister.

Now, with a pro-Nazi puppet government installed in Hungary, and the Nazi-like Arrow Cross as ready henchmen, Adolph Eichmann—SS-Obersturmbannführer and one of the chief organizers of the Holocaust—could get to work. Eichmann began his orders to carry out the four-step “final solution” to the Jewish Question.

FIRST Label all Hungarian Jews with yellow stars.

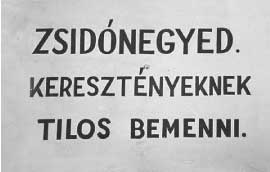

SECOND Concentrate Jews into demarcated ghettoes (forcing them to surrender most of their belongings).

THIRD Put them on trains headed to the concentration camp at Auschwitz/Birkenau: 60 people per car, 45 cattle cars per train, four trains per day. (The Roma were taken too.)

FOURTH Separate Jews into people who were useful for slave labor and those who were not. Immediately send any Jew unfit for work to the gas chambers. Make the others work until the hard labor, poor rations, and terrible living conditions inevitably killed them.

This process was applied to the Jews in Marcali, as well as every rural town across Hungary.

One thing that’s remarkable about the Holocaust in Hungary is that the Hungarian Jews were the last large remaining group of Jews in Europe. Eichmann had perfected this system elsewhere, and it was implemented nearly flawlessly. In fact, Eichmann arrived in Hungary with only 200 men and was surprised at how enthusiastic Hungarians were to carry out the plan. Hungarian authorities even insisted on dispatching more trains a day than Eichmann thought to be feasible. What is so shameful is that so many people knew what was happening by 1944 and still did nothing, including the Allies.

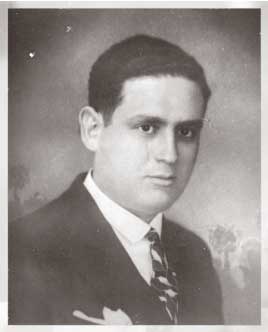

MOST of the Jewish men under 45 were already gone, assigned to forced labor battalions in which many would perish. They included Marcali’s town clerk, Ferenc Satler, judge Jenő Goldschmid, tailor Imre Weiss, butcher Moshe Rekhnitzer, grain merchant Pál Feuermann, the Scheiber brothers (László and György, whose father owned a downtown store); and the Lichtenstern brothers (László and Imre, also sons of a downtown merchant).

Perhaps Heller was used as a guinea pig to clear the land mines (Hungarian soldiers reportedly bet on which Jew would be blown up first).

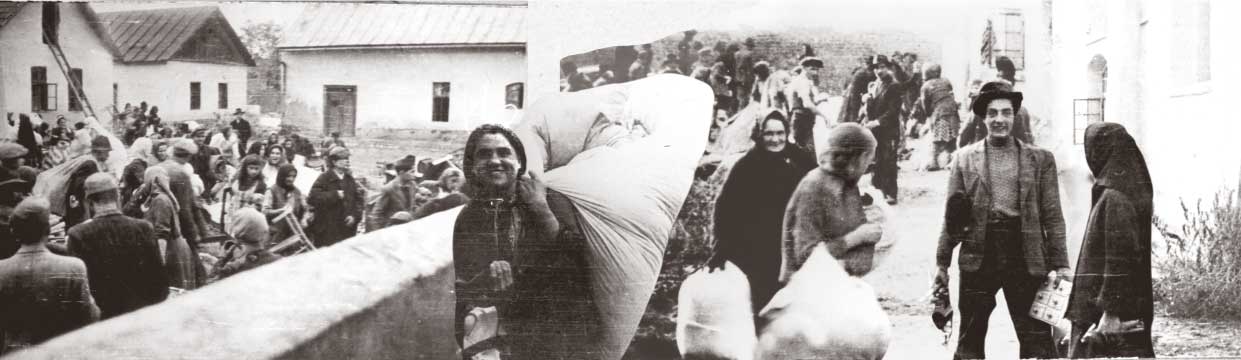

Once the local officials had tagged and marginalized Marcali’s Jews, they set to work disposing of them. During the afternoon and evening of June 9, 1944, efficient Marcali authorities rounded up those Jews who still remained in the city—mostly women, older men, teenagers, and children—and forced them into the synagogue’s courtyard; some Jews were also taken to the brick factory and others to special detention houses. It took all night long to bring the Jews together, but the local police were well ahead of schedule.

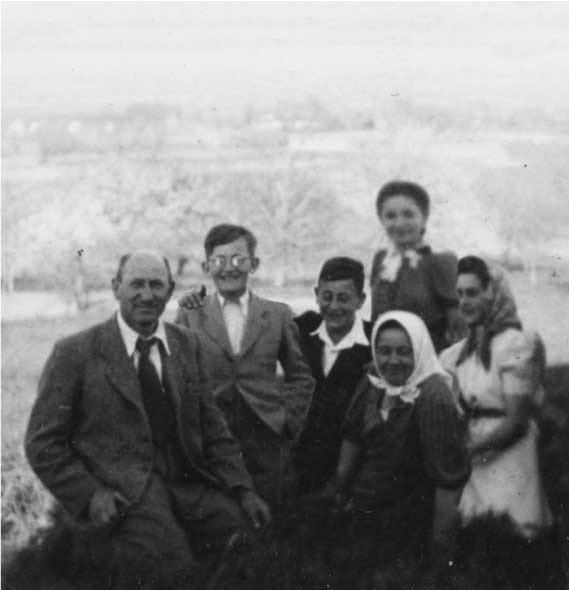

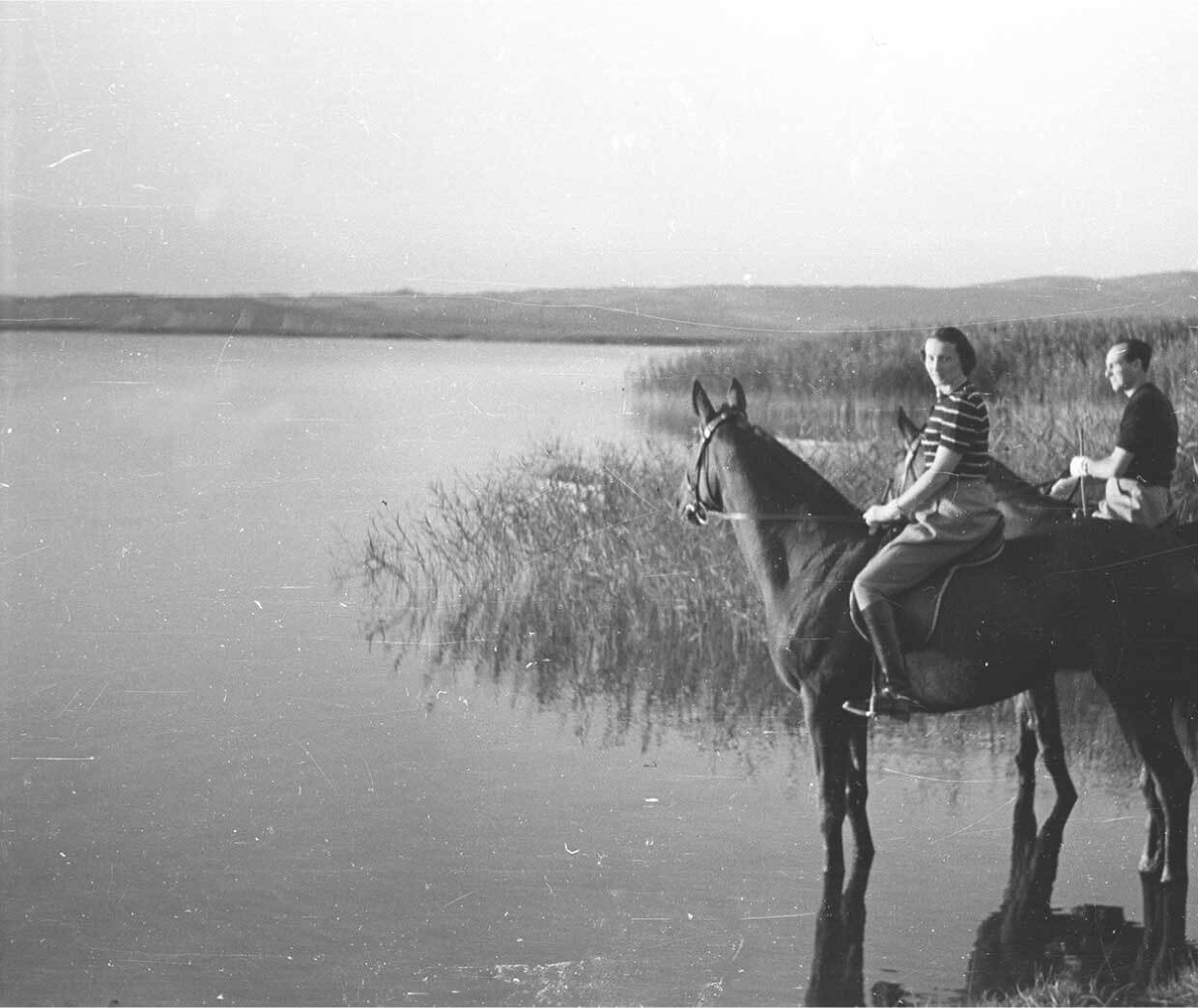

Netti and Sándor Steiner and their adopted son, Sándor Landler Losonci, were among the Jews imprisoned in the courtyard. Netti was an animal doctor; not officially, but she healed all the horses in Marcali, sometimes caring for up to 25 horses at a time in the family’s large barn. Even the police took their horses to Netti Steiner when they were ill. Sándor Steiner was a horse trader. They had a big house, quite a lot of land, and people who worked for them in the fields. They had no children until 1940, when 9-year-old Sándor, who had been an orphan since 1935, was placed in their home. Unlike every other home he had been in (where he was treated like a slave), the Steiners immediately loved him. He loved them back. It had been a beautiful four years with the Steiners and their many horses. Now he was 13, en route with them to Auschwitz.

Some Marcali Jews, for example, the three Stern brothers, Tibor (27), Jenő (29), and László (30), were killed before they even left the Marcali synagogue courtyard.

AFTERa night in the synagogue courtyard, local police took the Marcali Jews to a ghetto in Tab, a neighboring town with a slightly higher percentage of Jews (15%). In a few weeks’ time the police trucked this region’s Jews to Kaposvár (the largest city in the county) and then packed them onto train cars for a four-day journey to Auschwitz without food, water, or room to sit down. Many died en route.

"LOTS OF PEOPLE

DIED IN THE WAGONS.

THERE WAS A WOMAN

WHO WENT MAD.

SHE WAS SCREAMING

AND YELLING

AND TOOK OFF

ALL HER CLOTHES.

WE WERE LIKE SARDINES...

WE COULDN'T EVEN STAND"

- SÁNDOR LANDLER LOSONCI

Sándor Landler Losonci put his hand out to capture raindrops and fed them to his adopted mother, Netti. The Nazis gassed most of these Marcali passengers as soon as they arrived at Auschwitz. These townspeople included:

Sándor Landler Losonci, 13, was spared from the gas chambers by pretending he was 18. He became an experimental subject of the Nazi doctor Josef Mengele—injected with all sorts of solutions. When Mengele lost interest, the boy wound up processing gassed bodies at the crematorium with 30 other boys and young men, every day, from 6 a.m. until evening.

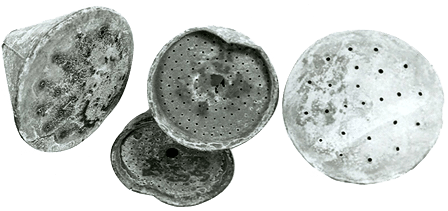

His main job was to pry the soap from the dead people’s hands and give it to the newcomers. The pretense, after all, was that this was a shower.

Shower nozzles used to gas the Jews and Roma.

INall, 185 Marcali Jews disappeared that summer in 1944; only 37 survived (Sándor Landler Losonci was one of them).

Meanwhile, non-Jewish residents in small towns like Marcali gleefully robbed their Jewish neighbors. They also moved into their houses.

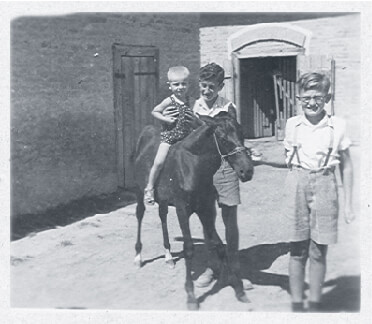

While close to ten percent of Marcali townfolk were being gassed to death, Ari and Gyula were comfortably engaged with their Budapest cousins, Géza and Ica, and little Miklós—the boy from the apple farm across the street. (Miklós would later recall how the Fábos’s farm was one of the biggest and best-run farms in Marcali). Even with so many Marcali residents vanishing from one day to the next, some days still went by prosaically, as if no war was going on.

ANDyet, despite their superior armaments, and their masterful killing centers, and their terrifying skills at destroying human dignity, Germany was losing the war.

-

International protests that summer had temporarily ceased the mass slaughter, and the Budapest Jews were so far spared.

-

By September 1944, Soviet forces had crossed the border into German-occupied Hungary.

-

By October 1944, Horthy—so torn between the Germans and the Soviets—determined that the Soviets were the lesser evil and announced an armistice with the Soviet Union.

But Hitler had other plans.

He ordered his henchmen to kidnap Horthy’s son, Miklós Jr., (dramatically wrapping him up in a carpet!) and forced Horthy to abdicate his regency (sign here, Mr. Horthy), putting Arrow Cross leader Ferenc Szálasi officially in charge of Hungary.

Now Szálasi continued with the Jewish annihilation, even as Soviet troops were invading the country.

And so from November 23, 1944, onward there were mass executions of Hungarian Jews and death marches for all the Jewish labor battalions in and outside of Hungary.

By December 1944, there were daily executions throughout Budapest—in the ghettos, on the streets, in hospitals, on the banks of the Danube. This period was a killing frenzy.

Brave people tried to prevent the mass murders.

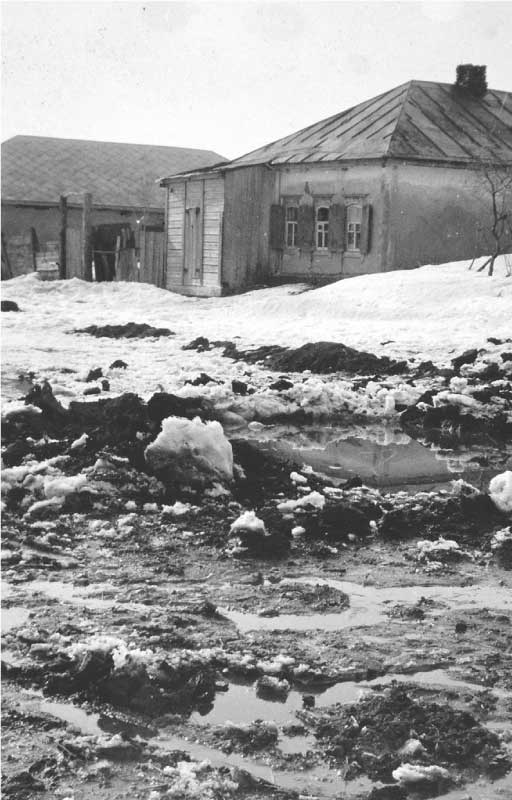

INearly December, Soviet forces arrived in Marcali, marking the beginning of a five-month battle against the Germans over the oil fields south of Lake Balaton. Oil fields near Marcali! It was Germany’s last chance (and not a good one) to win the war. And my family’s farm was right on that front line. War had finally arrived on their doorstep.

Before the Soviets confiscated their large farmhouse on December 4 (establishing headquarters there), my grandparents (Pista and Gizi), my great grandmother (the elderly Regina), Pista’s younger sister (Erzsébet), and Ari and Gyula, escaped to a friend’s house. (My great grandfather István had died of natural causes just a few weeks earlier.) However, the Soviets soon found them and herded them into a one-bedroom house with 35 other Marcali townfolk. Ari had no shoes.

The Germans bombed Marcali for four days. Ari (13) and Gyula (12) lay on the floor, praying every time a deafening, whistling Stuka bomb narrowly missed the house.

As Soviet forces encircled Hungary—walking into houses without knocking, confiscating everything they saw—word spread that they were also raping women and hauling young men away to Soviet forced labor camps. The many types of Soviet soldiers—from gray-eyed, blond Siberians to horse-bound Cossacks to Central Asian Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Kazakhs—were all intimidating and perplexing to the Hungarians. Ari was told to disguise herself as an old peasant woman and smear her face with soot to avoid the attention of Soviet soldiers.

On the fourth day, the group was allowed to make a simple soup. Eating in shifts, they shared the house’s ten spoons among 40 people, but they could hardly get the soup to their mouths— their hands were shaking so crazily.

The German bombing campaign succeeded in pushing the Soviet Red Army into the Boronka swamp near Lake Balaton. Remember the Boronka swamp from the beginning of this story? This is where my family had gotten its start as farmers after 1848 (nearly 100 years earlier). Nazis took over the family farmstead in Marcali. It had been bombed. Two Soviet soldiers lay dead in Gyula’s bedroom.

The family plan was to drive their DKW car to my great aunt Mariska’s house near Héviz to flee the front line. In the dark, my grandfather, Pista, retrieved the car’s wheels from their hiding place and quietly put them back on the car. If this was The Sound of Music, the family would have rolled away, started the engine, and driven off to safety. But the Germans discovered the escapees, confiscated the beautiful, near-new cherry-colored car, and the family had to travel the scary 8 km to Héviz (all parallel to the German-Russian front) using a horse and carriage instead, bullets perilously whizzing by their heads.

It was goodbye to Marcali, at least for a little while.