ARIno longer had to wear soot on her face and live in constant fear of being raped by Soviet soldiers. Her family was in German-occupied territory now. Everyone felt safer in the home of Gizi’s aunt, Mariska.

But the family was now split up. Their father, Pista, and their grandmother, Regina, were back in Marcali, protecting the farm’s remaining animals and tending to the Soviet soldiers who occupied the main house, which changed hands between the Germans and the Red Army five times between 1944 and 1945. To placate the Soviets occupying their house, Regina served them goulash (gulyás). Meanwhile, Pista secretly unearthed treasures for his family’s survival: wheat, wine, potatoes, beans, smoked sausages, lard, salted pork, glass jars of pickled vegetables, money, guns, seed, and clothes, which he had buried all over the family property. In our family narrative, Pista’s hiding capabilities were nothing short of heroic. Every two weeks he delivered dug-up food to the family members near Héviz.

These trips were tense and frightening. On one occasion, a rocket hit the tree he was passing under; each time he traveled to Héviz and back again, Pista could have died. The Germans and Russians settled into the Lake Balaton region for the winter.

Meanwhile, the relentless Soviet Army encircled Budapest, and the city was being bombed to bits.

Budapest residents were starving and terrified, crammed into cellars or Jewish ghettos for fifty straight days. The Arrow Cross doubled its efforts to murder Jews on the banks of the Danube. And on February 13, 1945, the magnificent city—now torn to shreds—finally fell to the Soviets.

Joining Warsaw, Leningrad, and Stalingrad, Budapest experienced the devastation of hosting a major battle that reduced the city to rubble. By comparison, Berlin fell after two weeks and Vienna after six days. In the end, 38,000 citizens of Budapest died during the siege; about 15,000 were Jewish.

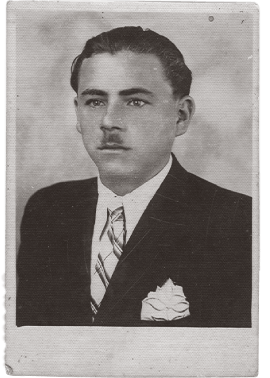

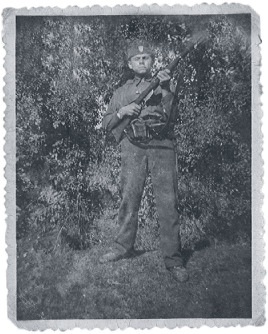

FERI(shown here) and Karcsi were two of these new recruits. They were second cousins to Ari and Gyula—Aunt Mariska’s sons—and they had all been living together in the small farmhouse near Héviz. Good bye, good luck Feri and Karcsi. See you soon (maybe, maybe not).

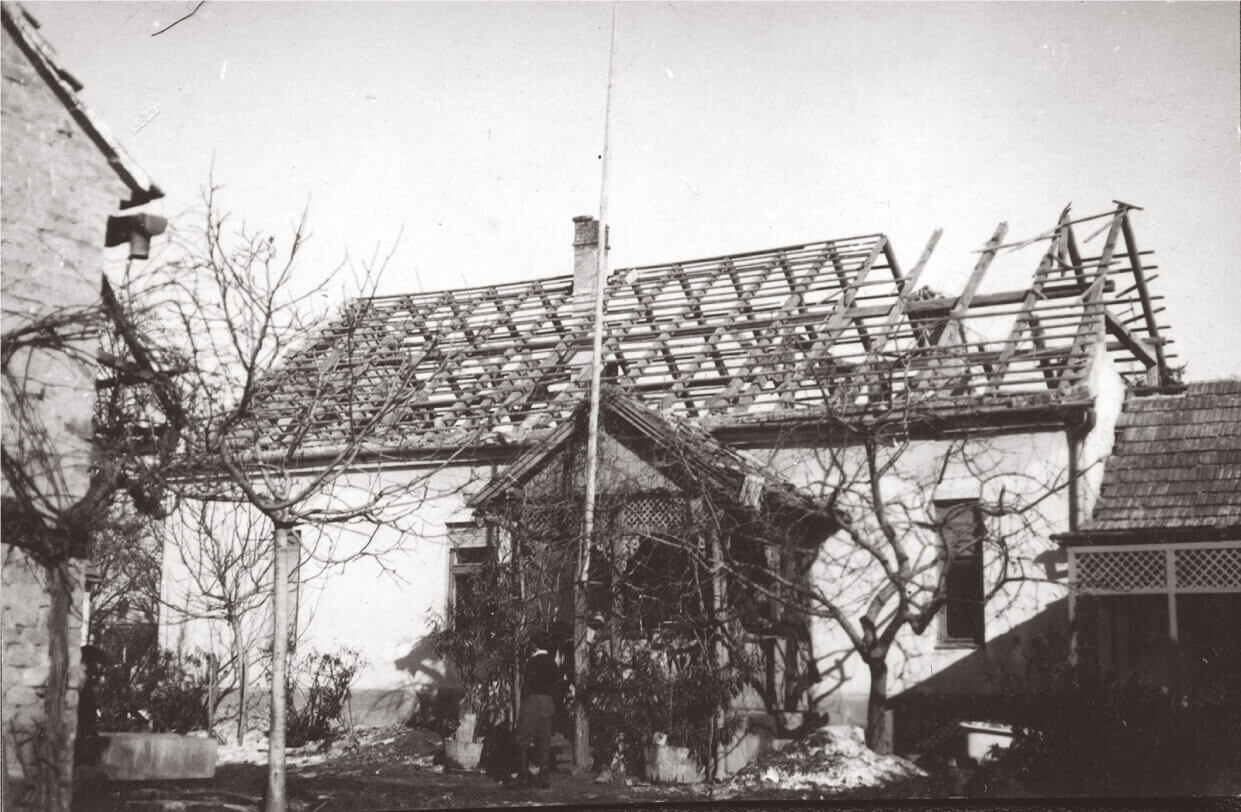

The two cousins fought in the ten-day-long German maneuver called the “Lake Balaton Offensive,” March 6-16, Germany’s last attempt to win the war. As its name suggests, the battle swirled around Lake Balaton … and right on my family’s property. Germans bombed the family house. But the Soviets counterattacked with such conviction that the German offensive failed miserably.

The war ended. The Germans lost, the Hungarians lost. Like thousands upon thousands of Hungarian men, Feri and Karcsi were captured by Soviet soldiers and taken to forced labor camps in the Soviet Union.

In Budapest, survivors crawled out of their cellars and worked to put their city back together again.

MYfamily returned to their bombed-out house in Marcali, sleeping in the barn and creating an assembly line to fix the roof.

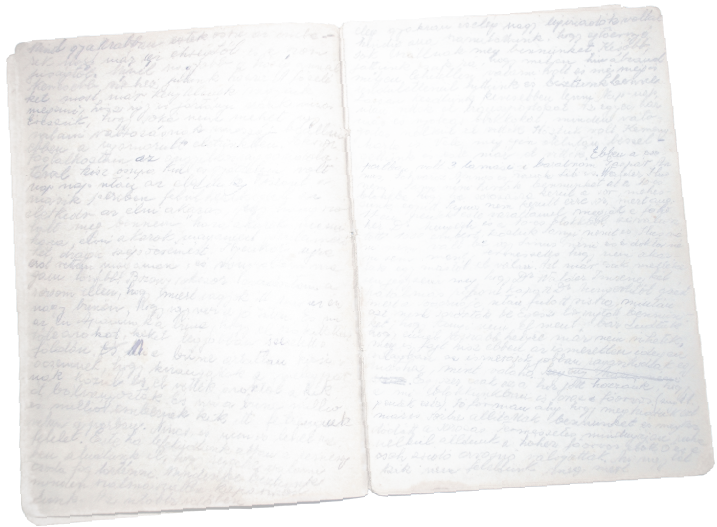

Júlia Bauer came home to Marcali, too. As a 22-year old Jewish girl who had lived through both Auschwitz and Birkenau concentration camps, she was one of only 37 Jewish Marcali residents who survived the war (184 were murdered). Like a Hungarian Anne Frank, she wrote a journal, chronicling the horrors of her camp experience and what she thought her life might be like on her return.

"Somehow everything has gone

cold; I don’t care about anything

and I feel as though my life

will be pointless from here on

out. Now, all the same, I try

to face life. But I dare not

think about the day when I get

home and nobody will be

waiting for me."

"Somehow everything has gone

cold; I don’t care about anything

and I feel as though my life

will be pointless from here on

out. Now, all the same, I try

to face life. But I dare not

think about the day when I get

home and nobody will be

waiting for me."

Júlia was hoping to find relatives, and also hoping to find her home just as she’d left it.

Around Marcali, residents were using her family’s furniture and walking around in her clothes.

Sándor Landler Losonci, now 14, also returned to Marcali from Auschwitz, only to be chased away from his parents’ house by other Marcali residents who now lived there; they had appropriated his family’s horse farm as well.

SOVIETsoldiers now occupied Hungary (and Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania). They looted factories, raped women, demanded war reparations, hauled young men off to Russia, seized large estates, and filled much of the population with fear and dread.

As the Soviets claimed every grand, opulent palace throughout Hungary, the Magyar nobility living in them fled the country. Most headed west. Their hundreds of years of not paying taxes or denying progressive real wages to their manorial workers had finally caught up with them. Soviet soldiers sent the furniture and chandeliers back to the impoverished Soviet Union and tore up the parquet floors.

WITH the aristocratic class now having fled, what was in store for Hungary?

During the “Big Three” meeting of World War II Allies in February 1945, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin met in Yalta, Crimea. At this point in the war, Stalin could call the shots and had refused to travel any further (he was also afraid to fly). The Allies had granted him a Soviet sphere of political influence in Central Europe. Soon this region became known as the Eastern Bloc, which ostensibly protected Russia from any future German aggression.

This was the Soviet psychosis. (Yes, a country can have a psychosis!) The Germans had attacked the Russians in both world wars and nearly 27 million Soviet civilians and soldiers had died in WWII alone. The Soviets were dead set on stopping German aggression from happening again.

In Yalta, Stalin promised that all Soviet satellite states (including Hungary) would be able to establish free elections and democratically choose their own form of government...

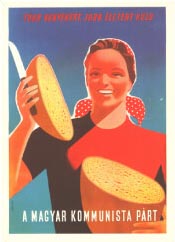

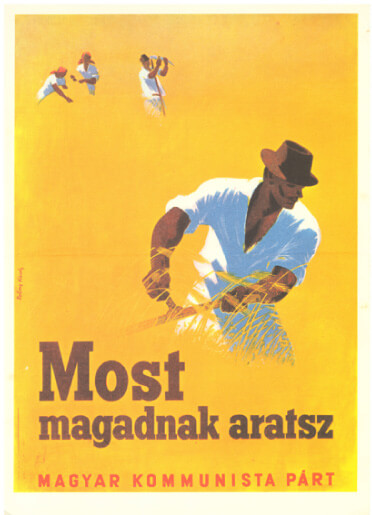

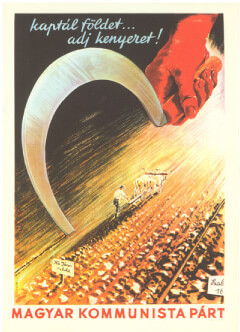

ANDthat’s the way it seemed it would go. At war’s end, Hungarian communists (many of them exiled in Moscow) arrived to play their part in this new Hungarian democracy. Their task was to convince the Hungarian population that communism was a great political and economic system. They organized factory workers, educated university students, held public forums, and planned parades, using every opportunity to extol the many benefits of communism: speedy modernization, land redistribution (“let the rich pay!”), and equality, maybe even for women. They described a future in which everyone would be prosperous.

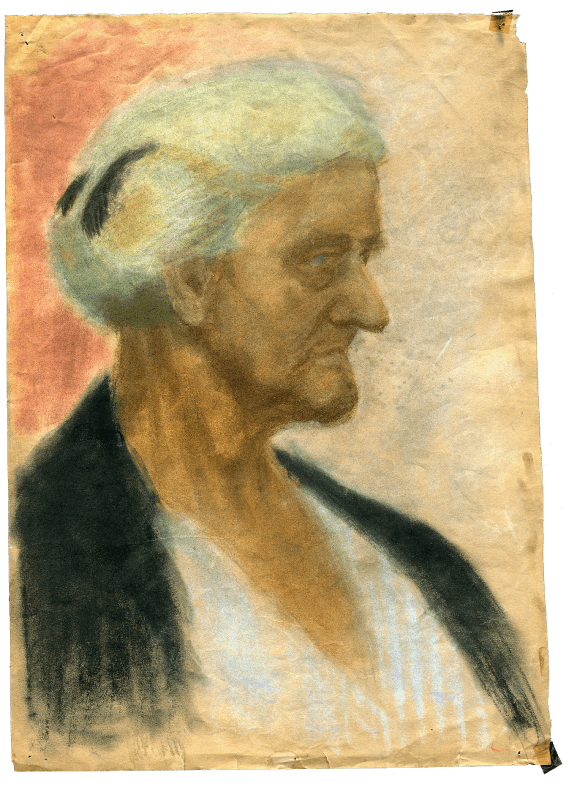

MARISKA GÁRDOS

MARISKA GÁRDOS

Feminists like the tiny, spirited Mariska Gárdos, a longtime journalist and leftist activist, joined the Communist Party in 1945 after a lifetime of alerting her male comrades in the Social Democratic Party about women’s issues (she was mostly ignored). As a Communist Party member, Gárdos co-founded the Democratic Alliance of Hungarian Women and moved to educate Hungarians on the benefits of cooperative societies.

Under the communist system, the needs of landless peasants and the industrial working class were supposedly prioritized.

“LET THE RICH PAY!”

“TURN PROMISES

INTO REALITY!”

“LONG LIVE

MáTYáS RáKOSI!”

Women would benefit from free nurseries, meaningful careers, and leisure time. Young people would get free education and advancement to positions of high responsibility within large, modern enterprises. Everyone, especially the elderly, were assured security and care in time of illness and disability. Land confiscated from the big estates and the Catholic Church—like the Széchényi estate in Marcali—would be distributed to the poorest peasants.

These proposals resonated strongly with many Hungarians.

Party membership reached 300,000 by August 1945.

MÁTYÁS RÁKOSI

MÁTYÁS RÁKOSI

The Hungarian Communist Party’s election campaign—fronted by their leader, Mátyás Rákosi—was lavishly funded by the Soviet Union. Selling communism to Hungarians, however, was an uphill battle. The Soviet occupiers (who had raped women and ordered young Hungarian men to Russia) were unpopular, and news of Soviet strife under Stalinist rule had reached Hungary.

Hungarian communists sought legitimacy by linking their party to Magyar nationalism. They positioned Lajos Kossuth, leader of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence, as a proto-communist hero, and envisioned a new “Hungarian democracy” distinct from the Soviet Union.

“HE WHO DOES NOT WANT

TO SEE LAND GIVEN

TO THE PEASANTS,

WHO WANTS TO RETAIN

THE SYSTEM OF ESTATES,

IS AN ENEMY

OF HUNGARIAN DEMOCRACY.”

- MáTYáS RáKOSI

Like a number of leading communists, Mátyás Rákosi was an atheist with Jewish ancestry. The fact that he was Jewish will become relevant later on in the story…

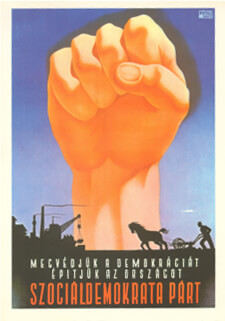

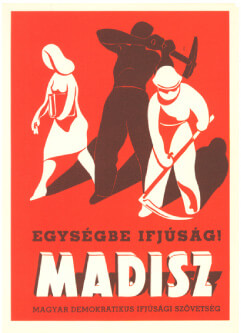

THEREwere other parties to choose from, too:

represented the working class.

was largely made up of intellectuals, but enjoyed some support among poorer peasants.

spoke for small landholders and middle class peasants.

These parties, as well as the Hungarian Communist Party, represented the working class, agricultural laborers, and smallholders. They had all been largely excluded from Hungary’s pre-war political system until this moment.

There was no party to represent the aristocratic class, as they no longer existed in Hungary. All fascist institutions were dismantled as well.

“PROTECTING OUR DEMOCRACY,

BUILDING THE COUNTRY”

“YOUTH IN UNITY”

“STRIVING FOR MORE BREAD,

A BETTER LIFE”

“NOW YOU REAP FOR YOURSELF”

“YOU RECEIVED LAND...

GIVE BREAD!”

As the leader of the Smallholders' Party, Zoltán Tildy ran on a ticket emphasizing the interests of modest landholders. His views were not unlike American President Thomas Jefferson's emphasis on yeoman farmers being the key to prosperity and democracy. Tildy supported property ownership, parliamentary institutions, and a “Garden Hungary” that would thrive with private smallholder farms.

“TOWARD A

GARDEN HUNGARY”

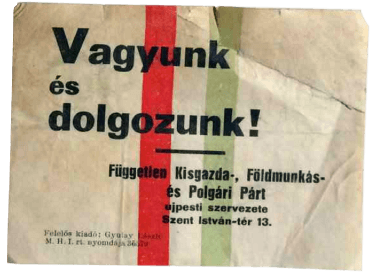

“WE ARE AND

WE WORK”

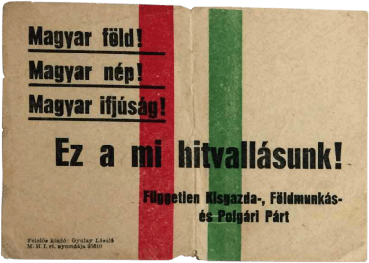

“MAGYAR LAND!

MAGYAR PEOPLE!

MAGYAR YOUTH!

THIS IS OUR CREED!

Despite the extravagant parades, powerful communist rhetoric, and Soviet money pouring into the Hungarian Communist Party's campaign, the majority of Hungarians preferred Tildy. He won a landslide victory in November.

Hungary was the first country in the region to hold free elections. The Smallholders' Party polled 57% of votes against the Hungarian Communist Party’s 17%.

Across Hungary, there was a general feeling of hopefulness with this new Hungarian democracy. The Tildy government would help put the country back together again.

Unfortunately, like the short parliamentary period immediately following the 1848 Revolution, Tildy’s success would only be a brief democratic interlude for Hungary.

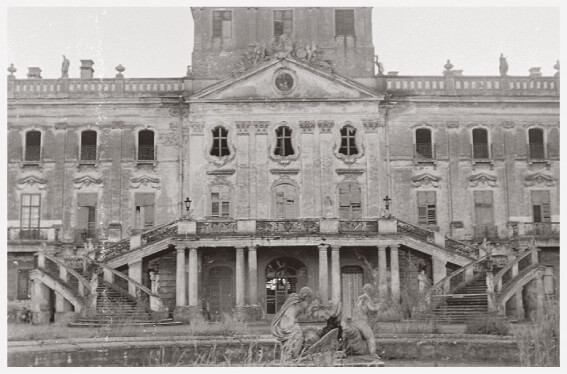

INdowntown Marcali, the large Széchényi castle had been repurposed as a hospital during World War II, used first by the Germans and then by the Soviets. The castle’s wealthy owner, Count Andor Pál Széchényi, died in 1943 at the age of 79. His wife, Countess Mária Szegedy Ensch Széchényi, quietly relocated to one of her manager’s tiny apartments, hoping no one would notice.

The castle remained a hospital, serving Somogy County from 1945 onward.

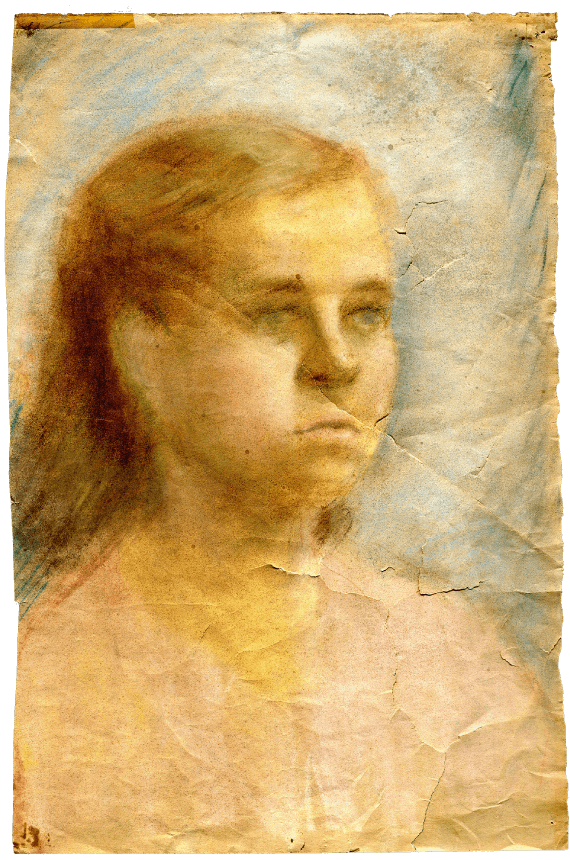

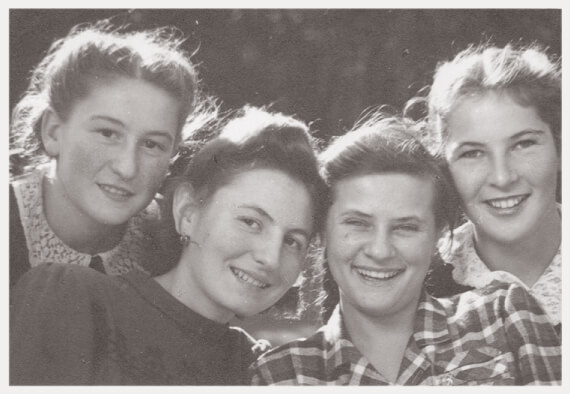

Meanwhile, Ari had moved to Budapest to study art and home economics in a Catholic boarding school.

These were hopeful times for her as well. She had always dreamed of being an artist. Being in the city was also liberating. Ari had enrolled with three good friends from her Keszthely school, and they were allowed to walk around Budapest in large groups. Even the school uniforms were less restrictive.

Exceptionally responsible with money (unlike Gyula, who spent freely), Ari was both careful and generous, recording each time (and how much) she gave to beggars in the street. And there were many beggars in post-war Budapest in 1945. Ari and her friends were able to bring up extra food from their farms to supplement the limited school offerings. They were far from starving, but so many residents in Budapest and other cities were.

The war was over. There had been successful democratic elections. Hungarian women, so ignored for the bulk of their country’s history, were perhaps sensing new possibilities. And yet, for many Hungarians, the aftermath of World War II was still a time of desperation.