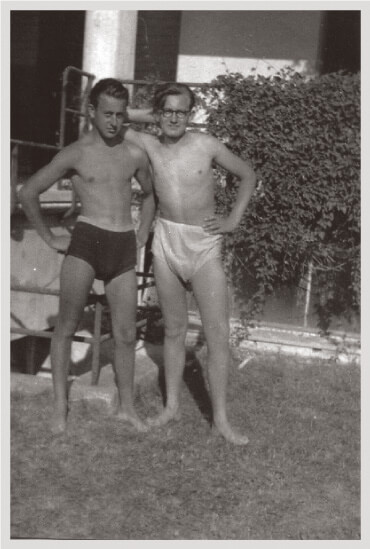

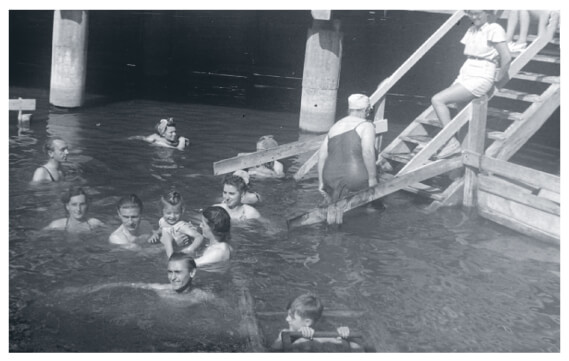

GYULAspent the summer of 1946 clearing heaps of artillery equipment left behind by Soviet and German armies, who had fought a war in his backyard. After each hot workday, he cooled off in Lake Balaton with Ari and their cousin Géza, who was visiting from Budapest and lucky to have family in the countryside: his city was still reeling from lack of food.

By 1946, my grandfather, Pista, had repaired the house, resumed planting crops with seeds he had cleverly hidden, recovered some livestock, and again started hiring farm helpers to nurture the fruit, vegetables, and crops produced on the farm.

My grandmother, Gizi, resumed her role as chief of the household. Working with Pista, she excelled at negotiating selling prices with buyers. During peak harvest, she orchestrated daily food production for up to 40 workers, serving hearty stews.

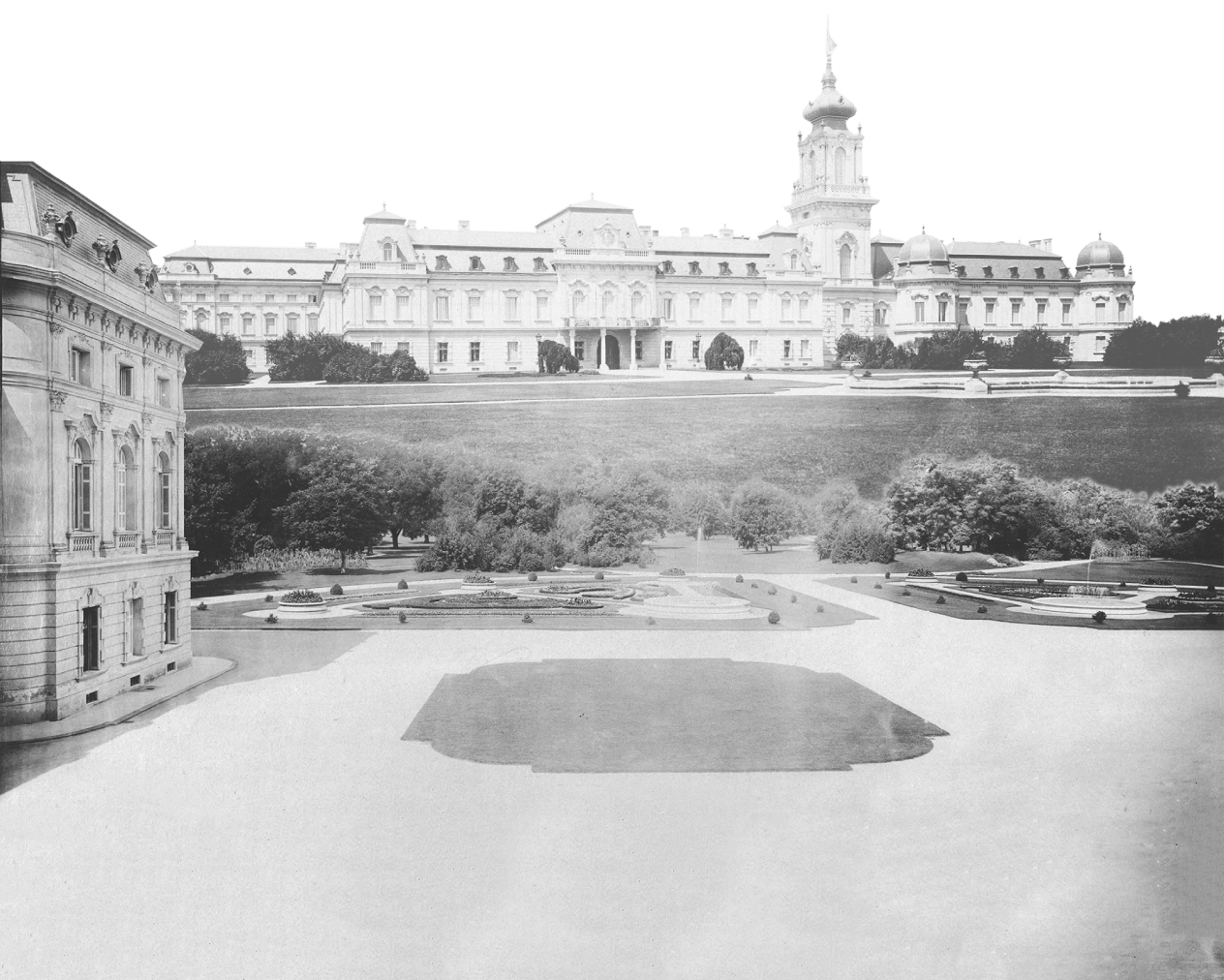

During the summer of 1946, Gyula learned that he would attend school that fall in a castle.

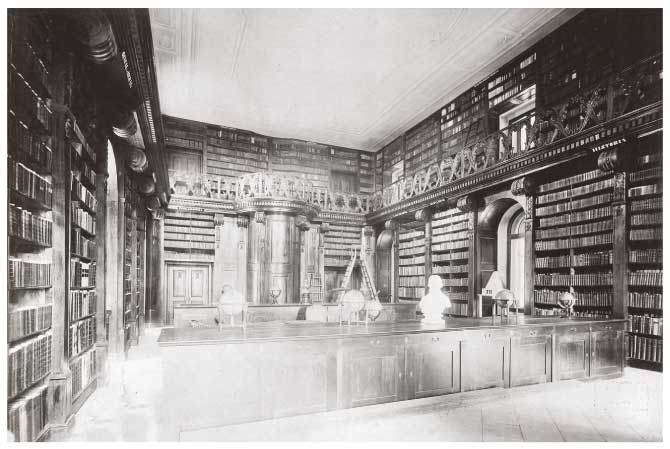

Keszthely’s famously extravagant Festetics castle—with 365 rooms, a lavish library, a mirrored ballroom, hunting quarters, and sumptuous grounds (all previously enjoyed by an elite few)—had become state property. Not many felt sorry for the fabulously wealthy Festetics family (now escaped to Austria), who had always had inordinate privileges and never paid taxes. The castle was turned into a public agricultural school.

For Gyula, this was heaven.

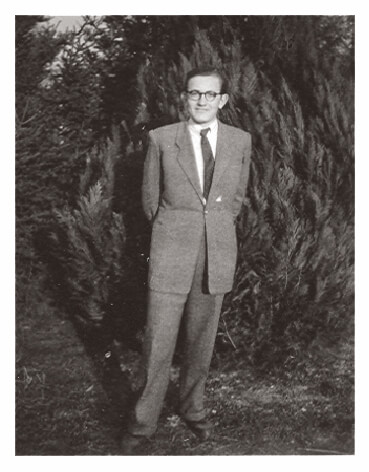

Away from the snobby lawyers’ and doctors’ sons at the austere Catholic boarding school, Gyula found his place among other like-minded farm boys at this new State Agronomy School.

As a male heir, he would inherit a large farm one day (not Ari, who was expected to eventually return to Marcali and get married to a farmer) and he was hoping to learn agronomy techniques to match the skills of his clever father. Maybe this way, he could impress him ...

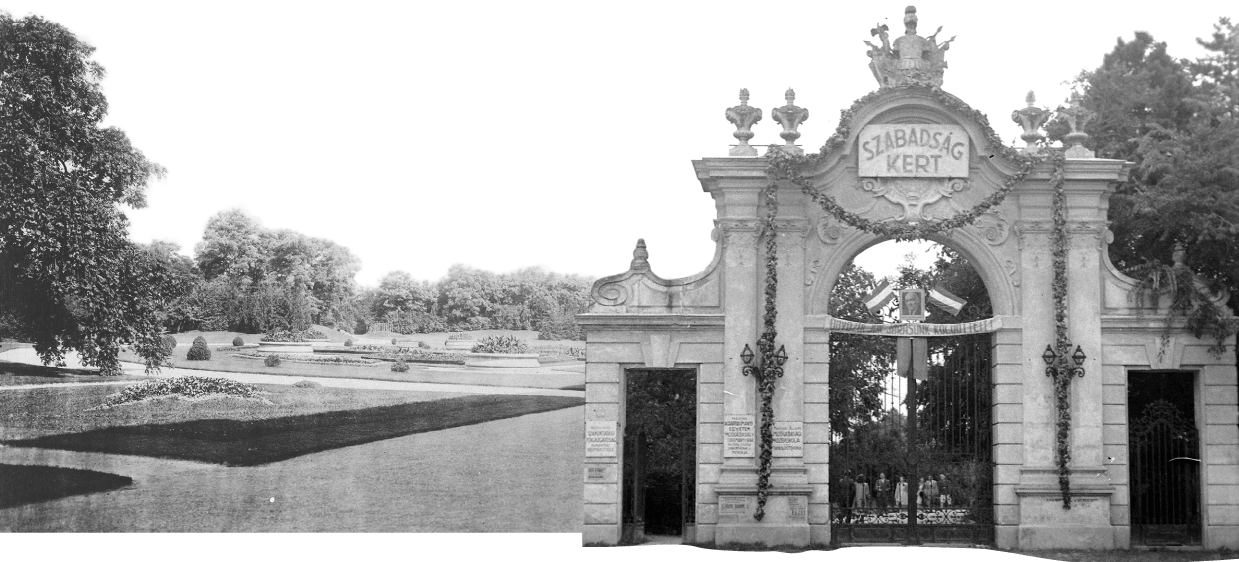

The new sign to the entrance of the Festetics Castle grounds, where Gyula now went to school, read "FREEDOM GARDEN." The private grounds had become a public park, open to all!

FREEDOM

GARDEN

Access to noble riches must have been satisfying to many Hungarians.

BUTa year after the war’s end, the camaraderie forged from collectively surviving the siege, or the Arrow Cross terror, or Auschwitz, or the Soviet onslaught, or any part of the tragic and horrible fears and starvation caused by the previous two years, gave way, simply and quickly, to hate.

People began to hate each other...for surviving a little more handily; for suffering a little less; for welcoming a relative home (never mind that this relative was permanently damaged—as was everyone— by this war); for finding a buried valuable; for wearing a stolen overcoat with lovely fur lining.

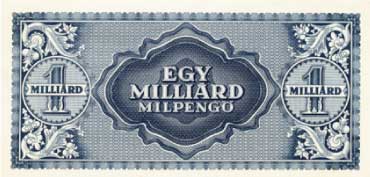

The hate was fueled by inflation, which had begun in 1945 but by 1946 had spun furiously out of control.

The Hungarian Pengő had become worthless.

Bartering became the only viable form of exchange. Hungry and desperate city and town folk hopelessly traded their last belongings to eat.

In this system, peasant farmers — like my family members — took advantage of the opportunity to make a handsome profit. When Pista unburied a 50-liter milk can filled with beautiful, sweet honey (that he had hidden so well it took him a year to find it), it was as if the family discovered liquid gold.

Ari and Gyula traveled to Budapest and got bids from five confectioners, ecstatically selling the honey for an unimaginably high price. On other occasions, Pista drove a carriage trailer of food up to Budapest in exchange for fashionable clothing and other goods.

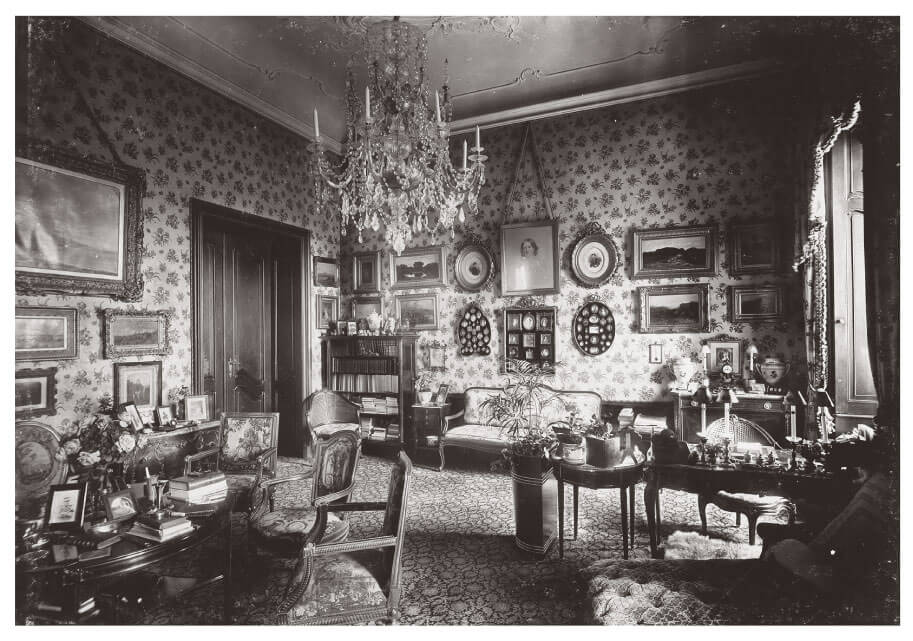

The spoon is and decorated with the Széchényi family crest. Demoted to a tiny apartment with no source of income, Countess Mária Szegedy Ensch Széchényi, bearer of an historical name, former occupant of Marcali's grand Széchényi Castle, was now living alone and bartering for food with her crested Széchényi silverware. She was also bartering with a girl whose family members once worked the Széchényi lands as destitute serfs.

This exchange was thick with irony. Perhaps for this reason, Ari still uses this spoon every day....It remains a prized possession.

Like Gyula studying agronomy in the Festetics palace, Ari suddenly had personal access to a piece of extreme privilege and wealth.

HUNGARY'Spostwar social upheaval, however, had only just begun. Faced with their 1945 rejection at the ballot box, Mátyás Rákosi and the Hungarian Communist Party abandoned any pretense of representing the majority of Hungarians. Their new tactic was to reward their communist supporters, and label all non-supporters of communism "enemies of the people."

The social roots of a dictatorship were born.

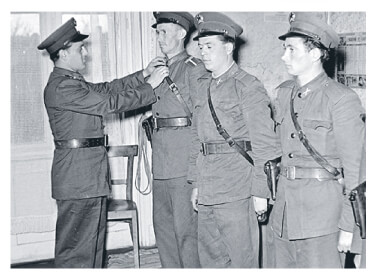

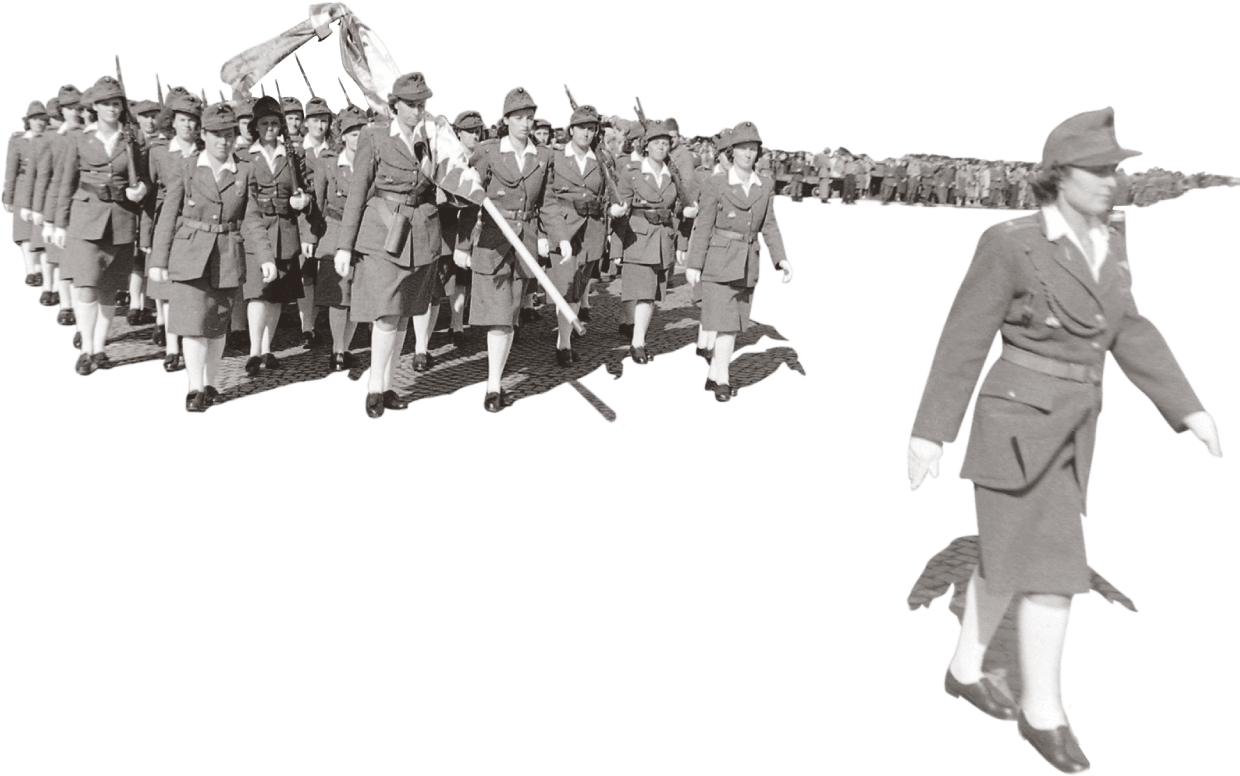

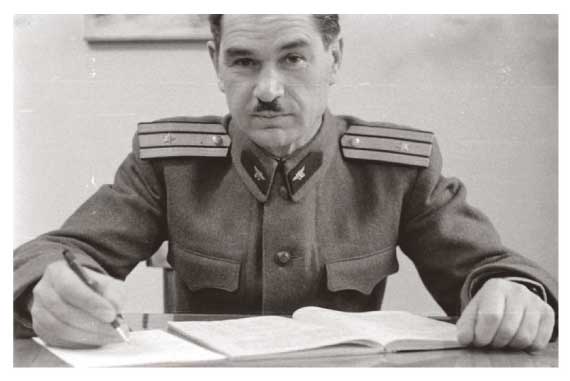

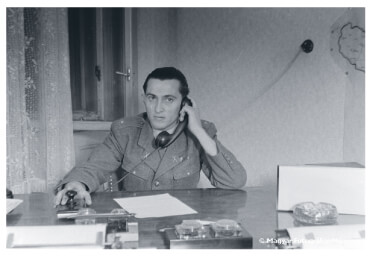

Ominous first signs that the communists were outmaneuvering the parliamentary majority came in the swelling ranks of men and women in new uniforms. In 1945 the Soviet occupiers had put Hungary’s general and secret police, youth, and personnel departments under strict communist control. These forces were now put to use.

Already a familiar presence, the men and women in uniform—fueled by the perks of Party membership—began to march more proudly and confidently around Budapest, and even on the streets of provincial towns like Marcali. They were "the people." Their enemies were all those opposed to communism...including the bourgeois, shop owners, and successful farmers (newly maligned as "kulaks," after the Russian word).

The new communist-backed police were somewhat like the Nazi or Arrow Cross soldiers in their attitude and character, but were now representing a different regime...

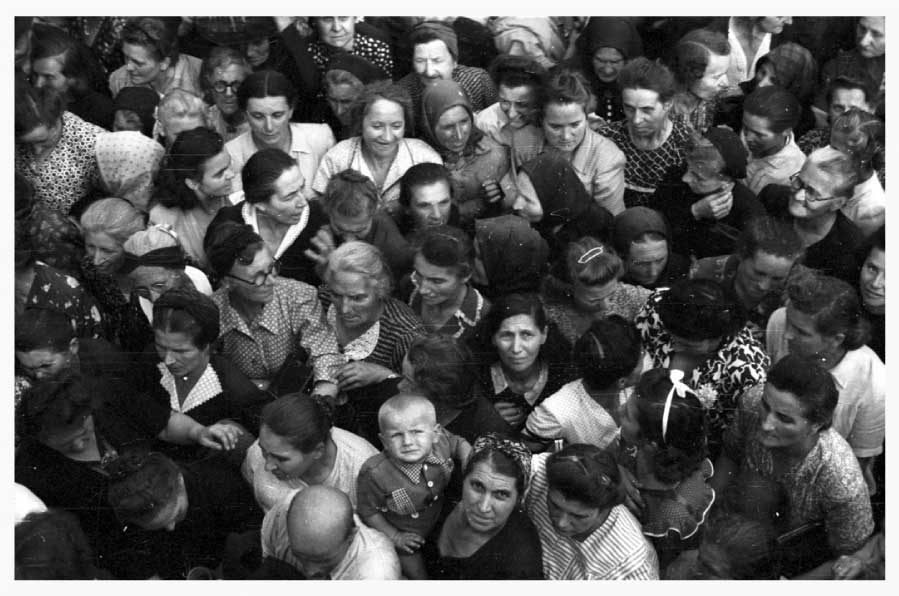

As for those not carrying a gun, some really believed in the power of social transformation. Others saw excitement in the drive to modernize the country. Some liked the idea of a country beyond nationalism—the communists promised an international brotherhood of workers. Some Hungarians, like women and Jews, saw a chance to rise up to their potential where before there was little opportunity.

Party membership grew to 7% by mid-1946.

1947

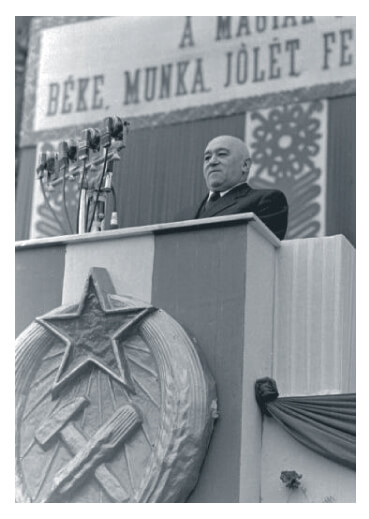

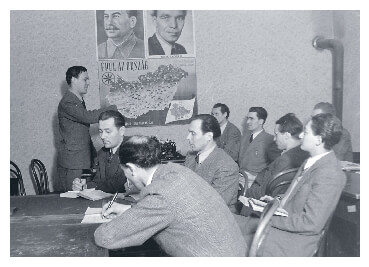

BUTpower wielded so strategically can go awfully wrong. By 1947, the Hungarian Communist Party was implementing its plan to force the Party and its values on the rest of the people. Led by the Soviet-trained Party leader, Mátyás Rákosi, communists abruptly removed President Tildy on trumped-up corruption and adultery charges (aimed at his son) and placed him under lifelong house arrest.

People read one morning in the newspaper that the left-leaning Hungarian Social Democratic Party had suddenly "merged" with the Communist Party. So-called "conspirators" against this new system were identified and abruptly put to death; anyone who publicly cared about Hungarian democracy disappeared into the torture chambers at 60 Andrássy Street. Books were destroyed, institutions were overtaken, and the special secret police—who seemed more and more terrifying and powerful by the day—appeared everywhere.

Mátyás Rákosi was so aggressive in replicating Stalin’s political and economic programs and terrorist purges that even Stalin advised more caution.

The model of Stalinist collectivization would be imposed on Hungary whether people liked it or not, and by physical force if necessary. Interestingly, a key ingredient to Rákosi’s rise was the careless oblivion of the Western powers, who watched from the sidelines as Hungary reeled into Stalinism. The Allies would risk nothing for Hungary, a former German collaborator ...

1948

BYJuly 1948, a Cabinet Decree stated that owners of larger estates or industrial companies would no longer own them. Never mind that some of these estates and companies had been cultivated across generations, or that those large companies were started from scratch by the owner's grandparents, or that they were successful and efficient enterprises.

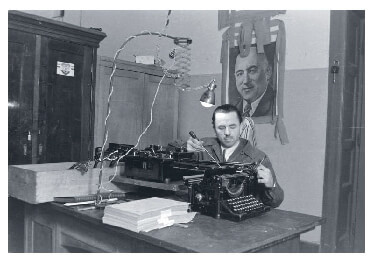

Under Hungary’s new communist order, all private enterprise was condemned as backward and exploitative. Owners were handcuffed and led away by special police in front of shocked (or maybe approving?) employees; companies immediately became state property, and low-level workers— members of the Party—were put in charge.

Party membership quickly became the key to social and professional advancement. Upon joining, the most unremarkable people happily found their way into positions of power.

A third-tier accountant became the minister of education, or an undersecretary, or an ambassador. An inexperienced journalist became a chief editor or a lauded writer of Communist propaganda. Meanwhile, droves of disenchanted intellectuals left the country. Novelist and journalist Sándor Márai left in 1948:

"IMBECILES ARE ALWAYS FOUND EVERYWHERE,

AND THEY CAN BE DANGEROUS

WHEN THEY CAST THEIR LOT

WITH AUTHORITY"

Corruption also became evident at all levels of the Party. Top Communist Party members confidently moved into the villas vacated by people now in jail (for questioning the system, an act of sabotage), or killed by the Holocaust, or deported to Germany.

Between 1946 and 1948, half of Hungary's 250,000 ethnic German minority were deported to Germany—116,959 people. The expulsion orders, given by Soviet occupying forces but opposed by the Hungarian government, affected any Hungarian who claimed either German nationality or German as tbeir mother language in the 1941 Hungarian census.

HIGHER-RANKINGParty members reaped unbelievable benefits. They were given automobiles. They were invited to parties at communist retreats around Lake Balaton and Héviz (previously reserved for the middle class elite), congratulating themselves that they had gotten so far for simply joining the communist cause.

Women, who had been invisible in Hungary’s overwhelmingly patriarchal society, were also allowed positions of moderate authority for the first time, and encouraged to apply for jobs typically reserved for men.

And unlike in previous regimes, Jews (those who had survived the Holocaust) faced no special obstacles to advancement. It was a time of opportunity for a large number of people.

Overall, this new "Party" assumed the privileges of the old class. Whatever longstanding inequalities might have been remedied by Marxism in theory were undermined by the opportunism, greed, and cruelty of yet another authoritarian regime.

INDecember 1948, the Communist Party imprisoned Cardinal József Mindszenty, the highest ranking leader of the Catholic Church in Hungary. He had been vocally opposed to the state’s seizure of Church-owned farmlands (the Church’s main source of income).

When he demanded compensation, the Party arrested him, accused him of treason and conspiracy, tortured him with rubber truncheons, and put him on trial where he publicly confessed his "wrongdoings."

Like President Tildy, he was put under house arrest indefinitely.

"I HAVE NO QUARREL WITH

THE RUSSIAN PEOPLE.

BUT I DO CONDEMN

THE POLICE STATE

TO WHICH THEY

ARE ENSLAVED"

- JÓZSEF MINDSZENTY

Mindszenty had also stood up to fascism and was imprisoned by the Nazis.

Meanwhile, confiscated land from the nobility’s large estates and from the Church was magnanimously distributed by the Party’s "Land Claims Committee" to peasants in every town (including Marcali). Peasant claimants bought a 60-centimeter-high stake with their name prominently displayed to mark their newly apportioned plot.

Hungarian Party members expected the peasants to be grateful for these generous gifts of land. Instead many were suspicious, remembering the unfulfilled promises made to agricultural workers in 1919 (the Socialist Revolution), and Horthy’s White Terror retaliations afterwards.

All Roma were excluded from the land reform process—entirely overlooked in this revolutionary transformation.

Indeed, peasants would soon have to surrender these plots when the land became part of collectivized or state farms in a few short years. But first, the communists needed to dismantle the middle class and abolish private ownership of mid-level farms and businesses.