1 hold = 5755 sq. meters (1.4 acres). 65 hold = 91 acres.

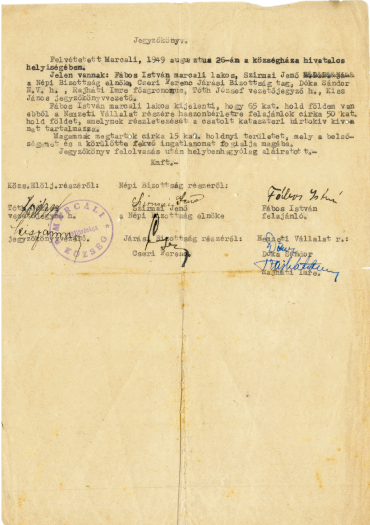

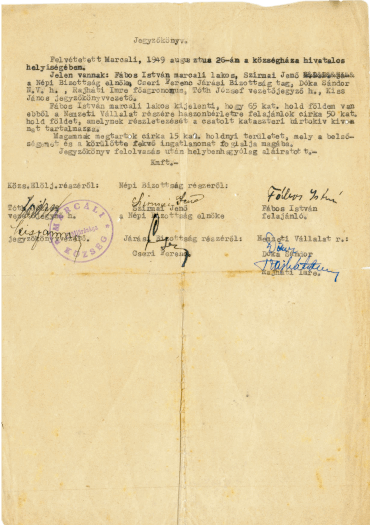

THEtranslation reads, "István Fábos of Marcali states that he owns 65 hold [approximately 91 acres] and pledges approximately 50 hold to the National Company. A detailed list of land registration numbers is attached. He will keep around 15 hold around his house."

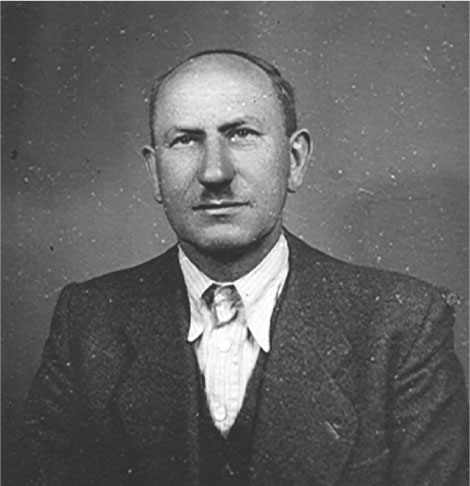

"ISTVÁN FÁBOS

FROM MARCALI

JENÓ SZIRMAI

PRESIDENT OF

THE "PEOPLE’s COMMITTEE

FERENC CSERI

MEMBER OF THE

MUNICIPAL COMMITTEE

SÁNDOR DÓKA

NATIONAL STATE FARM

IMRE RAJÁHTI

CHIEF AGRONOMIST

JÓZSEF TÓTH

VICE-CHIEF

SECRETARY AND

HEAD OF

THE TOWN OFFICE

JÁNOS KISS

NOTARY

Jenő Szirmai was president of the People’s Committee, but his power really came from being head of Marcali’s secret police (ÁVH).

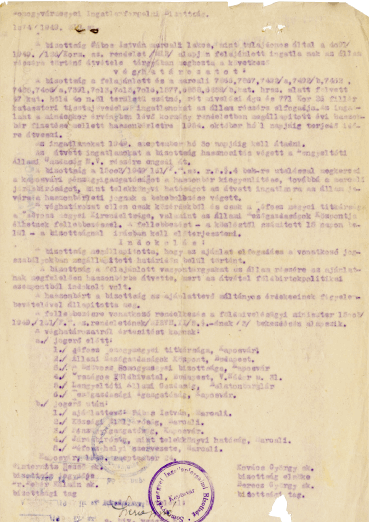

Here is the list of transferred real estate items and the rules of transfer; its language is in the style of a court order rather than a voluntary pledge.

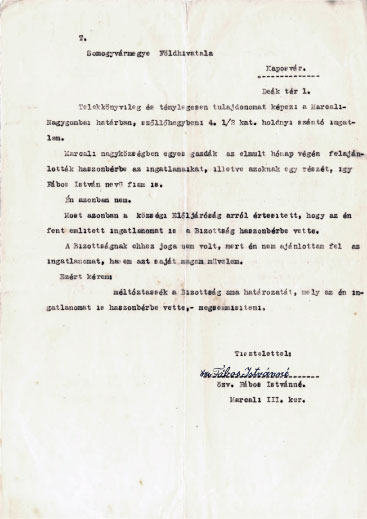

When my great grandmother, Regina, discovered that her significant share of the property had been lumped together under her son Pista’s name, she demanded a share of the remaining 15 hold. Regina wrote a livid letter of protest to the Land Registry Office.

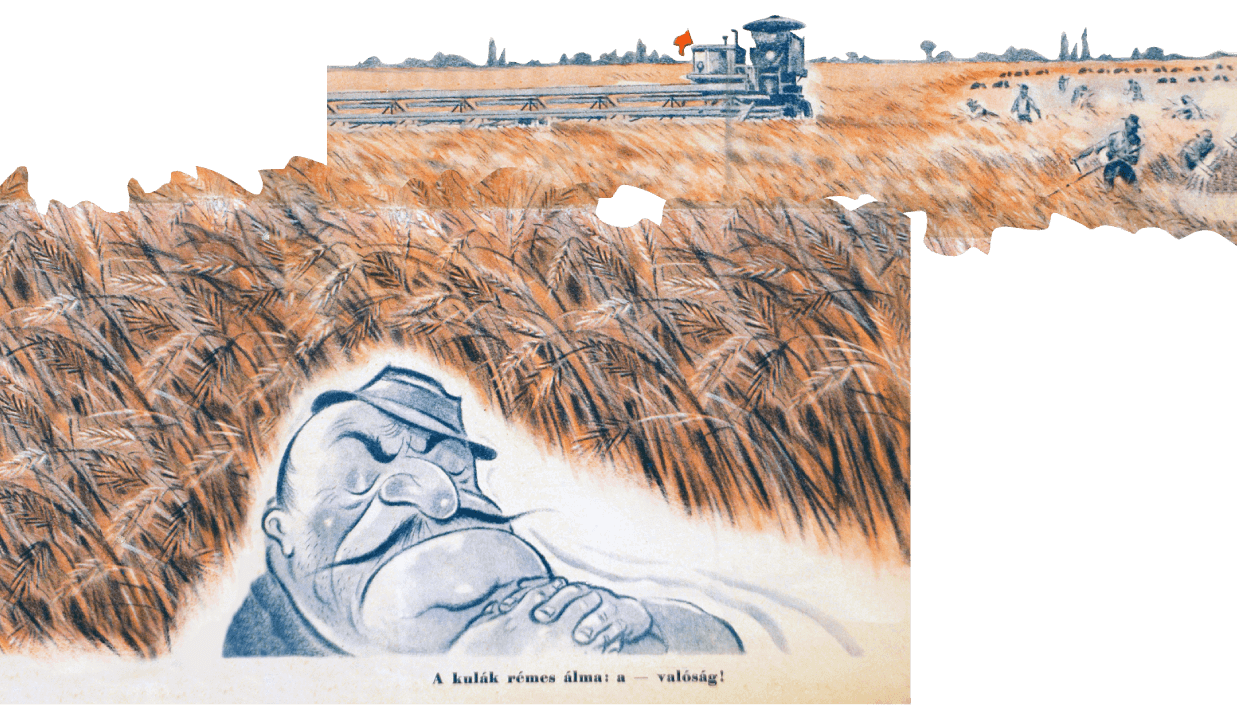

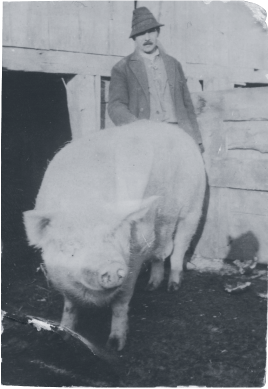

The Fábos family had somewhat prepared for this takeover. As wealthy, independent farmers (pejoratively called "kulaks"), they knew they were communist targets. They were seeing a non-stop string of anti-kulak cartoons in communist-controlled newspapers portraying landowners as greedy, fat, piggish men out to exploit the common farm workers—who were portrayed as gallant, honorable, hard-working (always male) heroes.

KULÁK!

"THE KULAK’S HORRIBLE

DREAM: REALITY!"

The Soviets used the same kind of propaganda to undermine successful farmers and ruin the integrity of family production in the Soviet drive for agricultural collectivization.

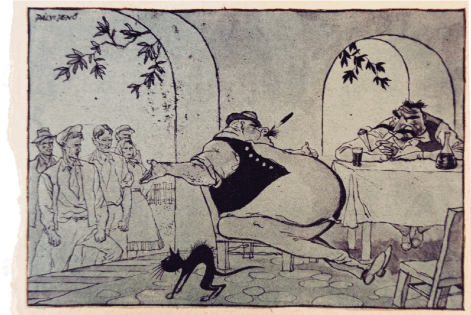

Indeed, these cartoons drew upon existing class stereotypes. As in all stereotypes, the distortions were based on partial truth: farmhands and kulaks often did dress this way.

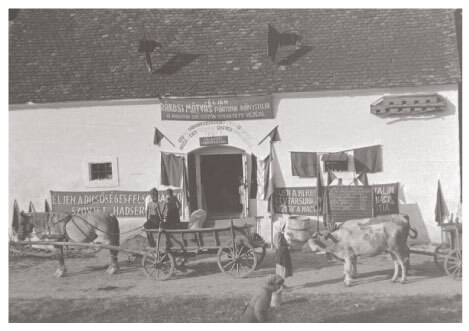

But the demonization of kulaks and the romantic portrayal of farmhands made it easier to justify dramatic social upheaval. Beginning with kulaks, the communist goal was to economically crush all independent farmers so they would willingly sign their land over to a collective farm where "life would be good," "democracy would flourish," and technological innovation would push Hungary into the modern era.

The strategy was to force all independent farmers to pay such high taxes, meet so many unrealistic grain, hay, meat, and milk quotas, and be paid so low by the state, that it was impossible to survive.

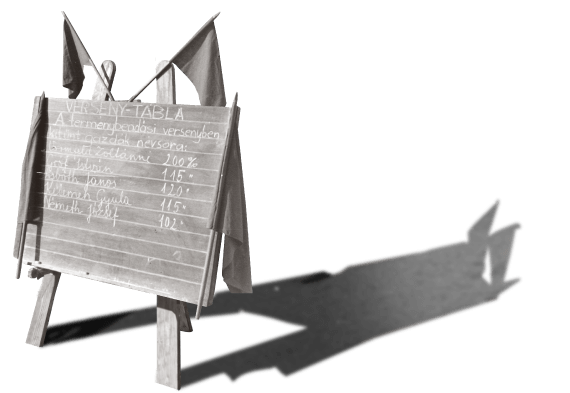

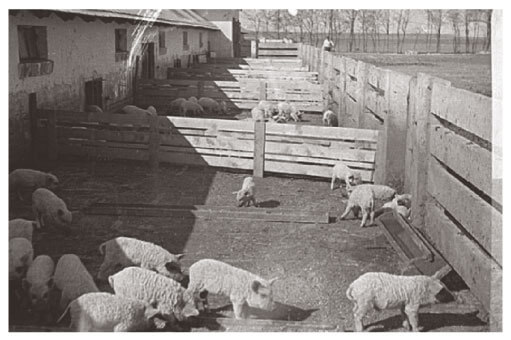

A collective farm joined land, animals, and machinery from neighboring farms together into a large group farm where every farmer was expected to play a part.

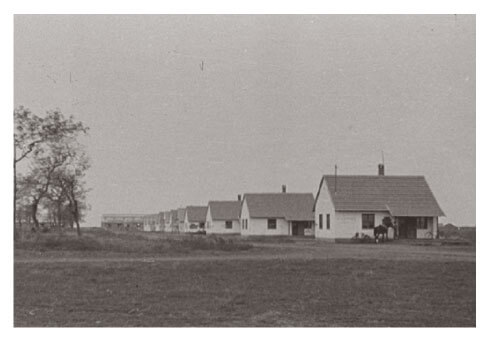

A state farm consisted of confiscated land from large landowners (including the Catholic Church) and later from kulaks. Agricultural workers with no land to join a collective were assigned to work on a state farm.

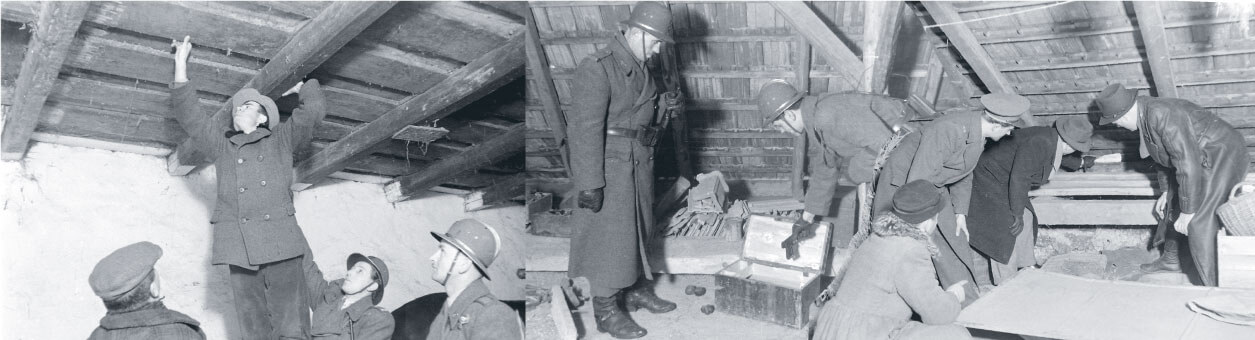

If economic pressure didn't cause the kulaks and other farmers to fold, communist authorities used direct force. They accused resistant peasants of "individualistic tendencies," found evidence of "sabotage" against the State, took the farmers to jail, and designated their land to a state farm.

WEALTHY PEASANT

ACCUSED OF SABOTAGE

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

OF HIDING GRAIN

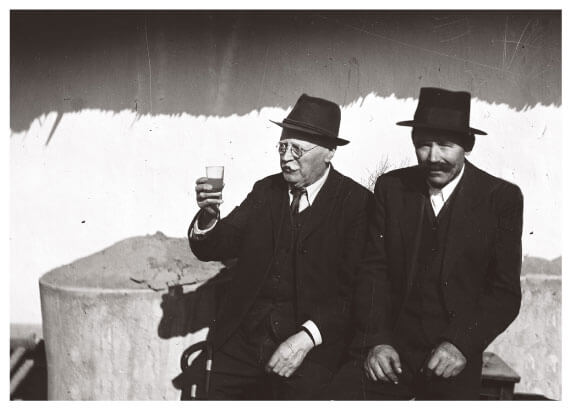

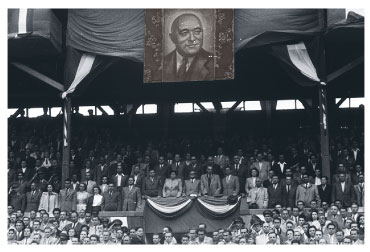

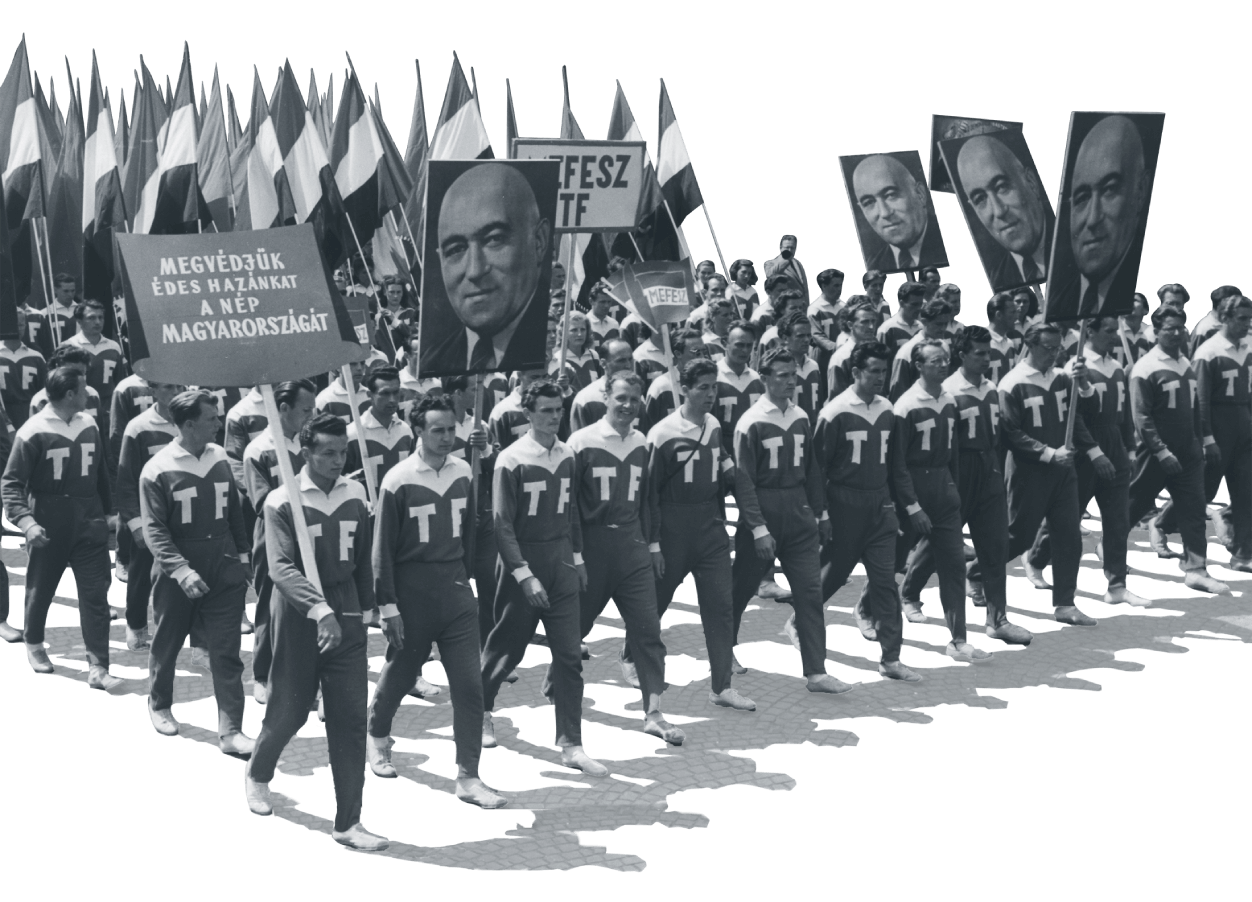

THEyear 1949 marked the full social transformation of Hungarian society into a fear-ridden, authoritarian state led by Communist Party leader Mátyás Rákosi, whose face was everywhere.

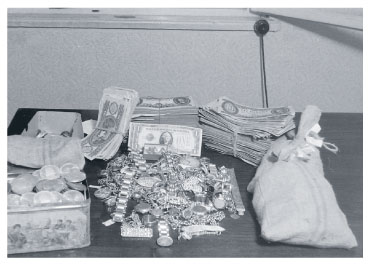

Even though Pista had signed over most of his land at gunpoint, he and my grandmother Gizi still tried to protect their assets. Who could guess how long the Rákosi regime would last? The previous summer, in preparation for the inevitable confiscation of everything they owned, Pista and Gizi converted their animals, farm equipment, and seeds into gold, German marks, and American dollars.

They hid the money and all the family’s other valuables around the farm. Many farmer did this, and every communist police officer knew that if they found these valuables (which allegedly belonged to the state, not to private citizens), then there was immediate cause for imprisonment. There was lots of digging in Marcali: digging to hide and digging to uncover.

By the end of the 1949 summer, Pista already had a number of sabotage charges accumulating against him:

- failure to produce sufficient grain (wheat, rye, oats, and barley) – his production was several tons below that expected by the government;

- failure to surrender enough live animals for meat (mostly pigs and cows);

- failure to produce sufficient milk.

- cursing the government.

This last charge was recorded in a communist ledger in 1948: When two communist youth appeared on the Fábos family farm asking for donations to their youth league, Pista was probably not thinking, as he angrily sent them away, that his comments would be grounds for imprisonment.

"!$%&*$# COMMUNISTS!!"

In 1950, cursing the government could amount to 10 years in jail.

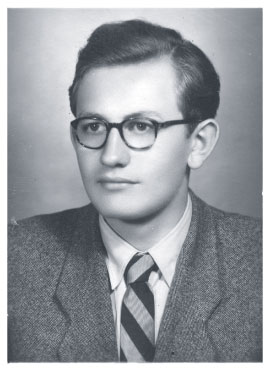

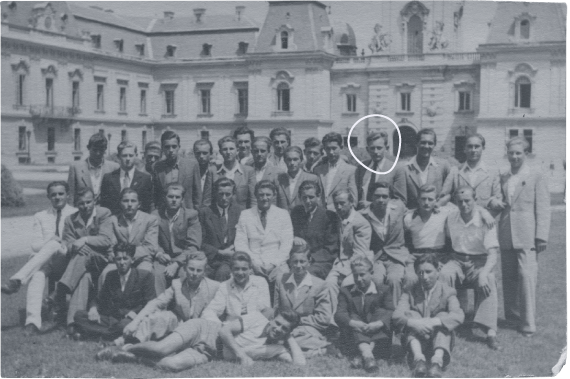

Gyula also learned that summer that he had been expelled from his fantastic agronomy school for being the son of an exploiting bourgeois farmer. For Gyula, the news was devastating.

ASMátyás Rákosi’s power expanded, Hungarians at the highest ranks were also under increasing pressure. Rákosi conducted arrests and show trials to firmly consolidate his regime.

László Rajk, who had organized the secret police (ÁVH), was Rákosi’s biggest rival in the Party, and was forced to submit to a dramatic show trial in September 1949.

ÁVH stands for Államvédelmi Hatóság, which means "State Protection Authority."

Rákosi’s team executed Rajk along with numerous associates, sending shockwaves through all levels of the Communist Party…

"IT DAWNED ON PEOPLE

WHAT A GREAT VILLAINY

HAD BEEN COMMITTED,

BUT EVERYONE REALIZED

THEY HAD TO KEEP THEIR

MOUTHS SHUT FOR THEIR

OWN SAKES...

PEOPLE WERE TERRIBLY

INTIMIDATED AFTER

RAJK’S EXECUTION."

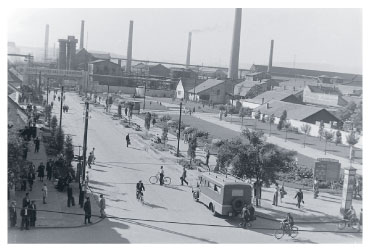

JÓZSEF BÁCSI

LOW-RANK COMMUNIST

PARTY MEMBER AND

CSEPEL FACTORY WORKER,

BUDAPEST.

Rákosi, "The Bald Murderer," was living up to his nickname, and the cult of Rákosi was now in full force. Hungarians who did not fully embrace their leader were immediately suspect.

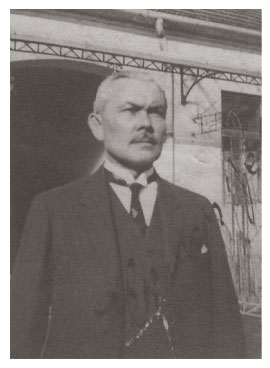

It was Marcali’s ÁVH chief, Comrade Jenő Szirmai, who escorted Hikman out of his shop at gunpoint. Hikman abruptly turned around.

"I FORGOT MY HAT,"

BÉLA HIKMAN

"IT’S NO LONGER

YOUR HAT,"

"IT BELONGS TO

THE STATE. MOVE,

YOU STUPID KONTÁR."

JENŐ SZIRMAI

A kontár is a an amateur or someone who botches a job.

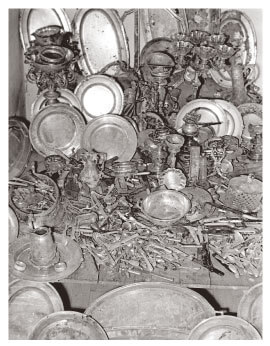

Hikman was not allowed to retrieve his hat or practice his craft again. His house, workshop, and Balaton villa were turned over to public ownership and, by the Party’s orders, he became unhireable. The award-winning blacksmith eventually scraped a living by illegally repairing sewing machines in his kitchen.

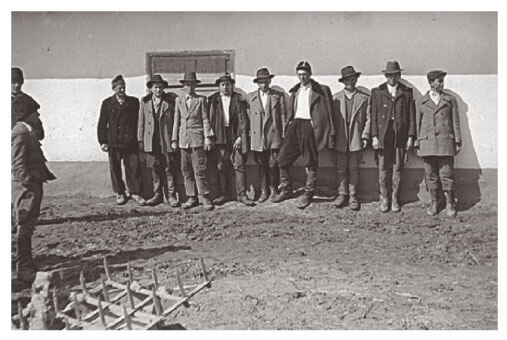

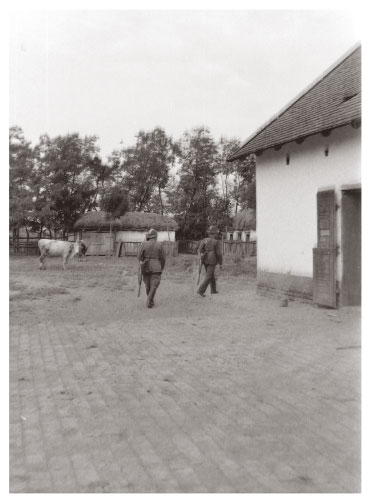

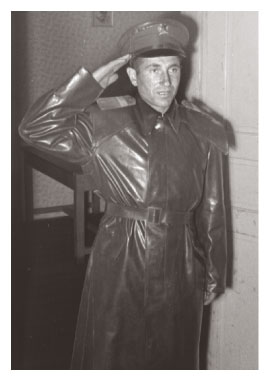

On October 6, 1949, the same Marcali ÁVH Chief, Jenő Szirmai, arrived with other officers to the Fábos family farm with orders to arrest my grandfather. (Szirmai reportedly rose through the ranks soon afterwards to become the director of the National Bank).

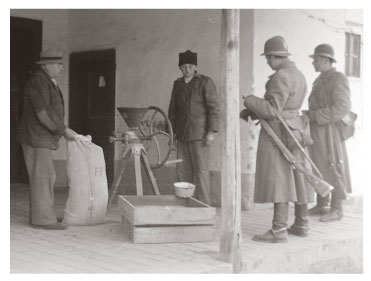

Magyar Rendőr/The Hungarian Policeman: an internal magazine for the Department of Public Order that was first published in 1947. Its purpose was to illustrate best practices for finding contraband, arresting people, checking papers, and interrogating farmers.

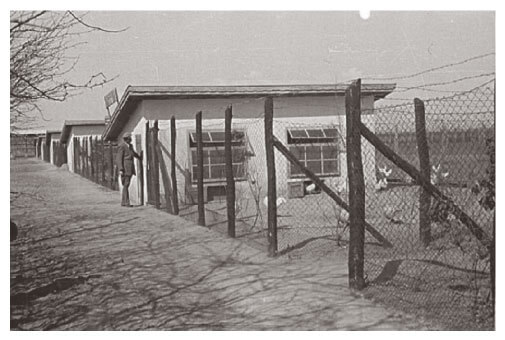

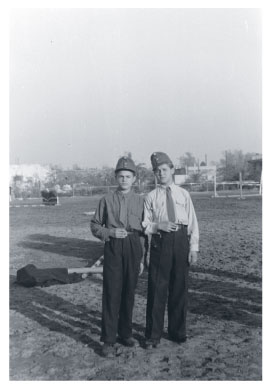

Gyula, who was 17, had to accompany two officers to the chicken shed where he knew his father’s guns were hidden. Guns throughout Hungary had been confiscated two years earlier, but Pista had handed over his lower-quality guns and hid his better hunting rifles so he could still hunt for food.

Gyula was in a cold sweat, trying very hard to not show any emotions. If the officers had poked the middle section of the chicken shed they would have found the hidden guns. They poked on either side. They didn’t find them…

Officials came up empty-handed with each family member, but they obviously had strict orders that day to make an arrest. So they identified pieces of Russian artillery equipment still left on the farm from WWII, labeled it "sabotage," and marched Pista three kilometers to the Marcali jail.

Gyula was instructed to follow, pushing the contraband in a cart. It was a bizarre little parade. Neighbors lined the streets to watch the first kulak arrested in Marcali. Gyula remembers people crying as he pushed the cart past them.

In 1949, 104,000 Hungarian farms were classified as belonging to kulaks.

After Pista’s arrest, many Marcali farmers were so intimidated that they surrendered their land to collective farms rather than have their land confiscated at gunpoint and face jail. This was the pattern across the country.

With the jailing of his father, Gyula had become the legal manager of his farm. He thus inherited all of Pista’s quota obligations and sabotage charges.

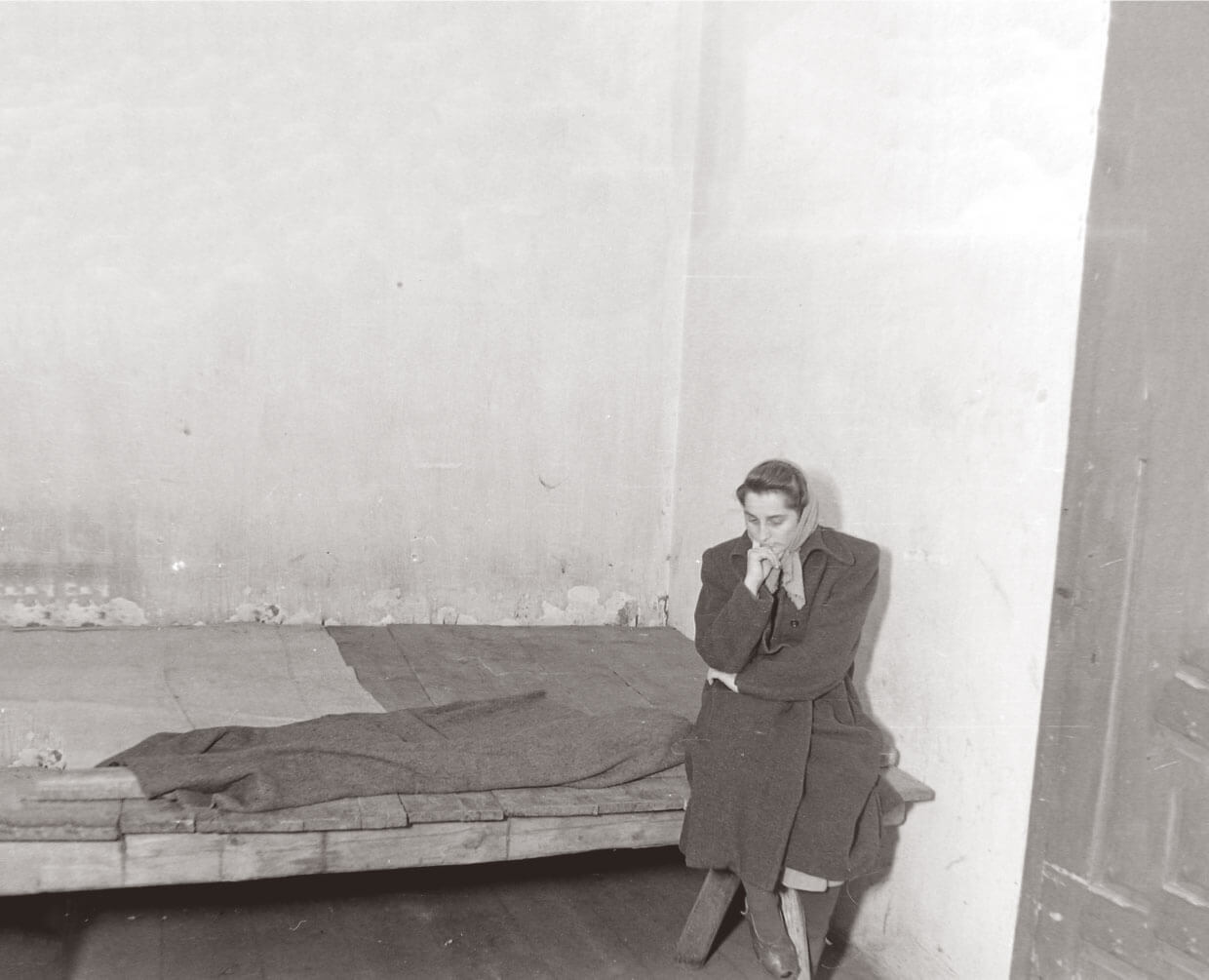

Ari returned from Budapest to come to her family’s aid. She luckily gained access to the house next door to Gyula’s Marcali jail cell and talked to him from the pantry window, giving him confidence to withstand the hourly beatings in the interrogation room.

As I heard this story growing up, I was proud too. I used my father’s torture to make myself interesting. Who’s father gets tortured by his government at age 17? It was even the topic of my college application essay.

But the story of the family’s victory rings sadly familiar in Hungary, both proud and torn. Like so many other times in the long and exhausting history of the Carpathian Basin, a new regime imposed a divisive vision redefining the Hungarian nation, tearing families and communities apart.

The Fábos family weathered the interrogation, but soon both father and son would be sentenced to years of back-breaking forced labor. The Fábos land and livelihood continued to be stripped away, as it was for Hungarians across the countryside.