BECAUSEthe Rákosi regime had labeled my grandfather a kulak, a saboteur, and an enemy of the state, the authorities had imprisoned him and assigned him to hard labor.

Pista endured a terrifying two-year journey that tested his ability to survive. He was:

Kistarcsa began as an infamous concentration camp for political prisoners during the Horthy era. Then it was used to house Jews during World War II before they were sent to Auschwitz. It held Arrow Cross collaborators after the war. By 1950, Kistarcsa had been repurposed again to house 2000 to 3000 opponents of the Hungarian communist state, mostly political dissidents.

Ari learned that Pista did not have a pillow, so she stopped sleeping with her pillow, too. After five months at Kistarcsa, communist officials told Pista he was finally getting a trial.

While in Pécs, Pista waited in the withering summer heat for his day in court. In September, 1950, the regime sentenced him to 18 months forced labor.

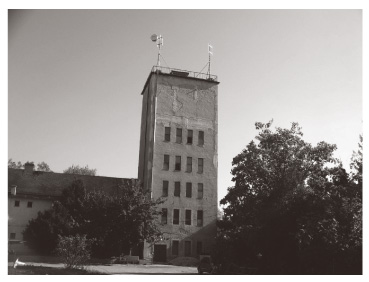

Pista's first two months were easier. The Bikal State Farm, north of Pécs, was on land that had belonged to the aristocratic Puchner family. Antal Szaniszló Puchner (1779-1852) was a Hungarian general who had received noble status because of his loyal service to Emperor Franz Joseph during the 1848 Revolution. Puchner built a grand castle at Bikal. But a hundred years later, communist authorities had chased the Puchner nobles out of Hungary, seized the property, and opened the Bikal State Farm in 1949 with a labor force of locals and prisoners. The farm produced fruit, hops, and rabbits.

Pista repaired tractors for the last two months of the growing season. Gyula and Ari could visit him.

As part of a growing group of forced laborers in industrial areas, Pista hauled heavy stones, helped build the Borsod Chemical Works (today a plastic factory!), and navigated life alongside 1,300 other inmates and harsh prison guards for nearly a year.

“AT FIRST WE ARE GOING

TO DESTROY YOU PHYSICALLY,

THEN PSYCHOLOGICALLY,

AND FINALLY WE ARE

GOING TO HANG YOU.”

“IN THIS COUNTRY

WE DO AS WE WISH.”

OPERATIONS OFFICER,

KAZINCBARCIKA CAMP

THESoviet Politburo gave Hungary’s dictator Mátyás Rákosi a long leash to do terrible things to wealthier Hungarians. From the Soviet perspective, Hungary needed to be strictly disciplined in order to eliminate its social backwardness; it was overrun with class enemies because of the aristocracy’s longevity as political leaders (until 1945) and the “unholy union” with Jewish capitalists, who had allegedly conspired to abuse peasants and workers. They ordered Rákosi to aggressively pull Hungary into line and “catch up” to the Soviet Union and the rest of the Eastern Bloc in creating a workers’ state.

My family was caught up in the punishment of an entire country. They were also caught up in Rákosi's Stalinist five-year “planned economy,” which was put into action in 1950.

coerced families to turn over their personal farms to huge, state-run, highly-mechanized farming operations.

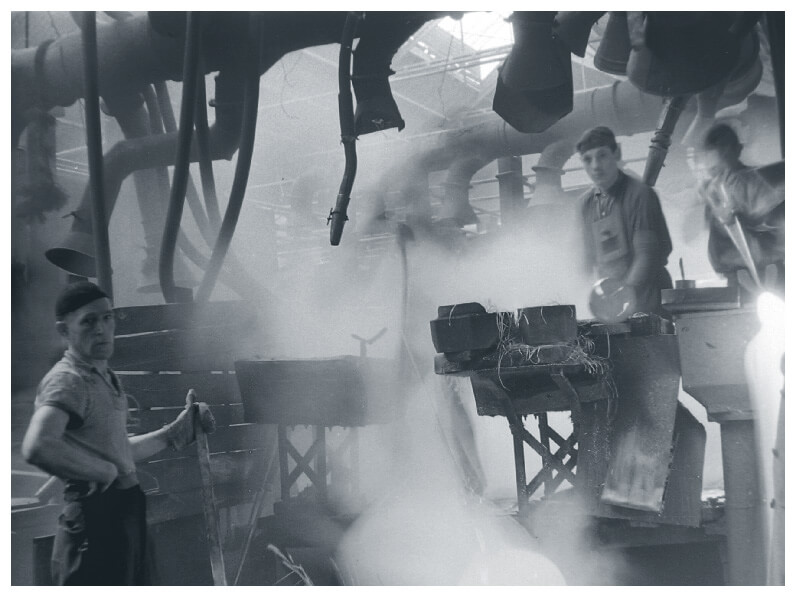

moved thousands of displaced farmworkers to mining jobs and large urban factories. Much of this heightened industrialization happened in northern Hungary. The region’s workforce changed dramatically in the first years of Rákosi’s five-year plan, from a modest number of relatively high-paid skilled industrial workers to thousands of semi-skilled and unskilled heavy laborers.

The industrial plan set out to expand Hungary’s labor force, increase production to unprecedented levels, and create a “new working class” to break down all the old workplace hierarchies:

SKILLED VS. UNSKILLED

YOUNG VS. OLD

URBAN VS. RURAL

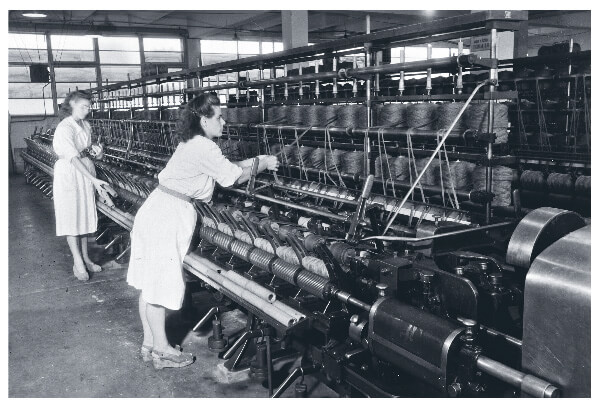

MEN VS. WOMEN

The state brought in young rural workers (displaced from their family farms) by the thousands, gave them crash training courses, and told them to work alongside seasoned factory workers and miners. State authorities also brought in women to work alongside men.

New “modern” towns like Kazincbarcika (where Pista ended up) and Tatabánya, which barely existed before this period, exploded overnight to become big, muddy construction sites saddled with all levels of dysfunction. No water. No soap. No fresh vegetables. Unreliable and overcrowded transportation to and from the worksite. Bread baked with particles of sawdust, pieces of wood, and pebbles…

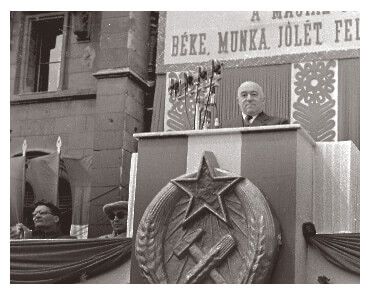

“PEACE, WORK,

WELFARE...”

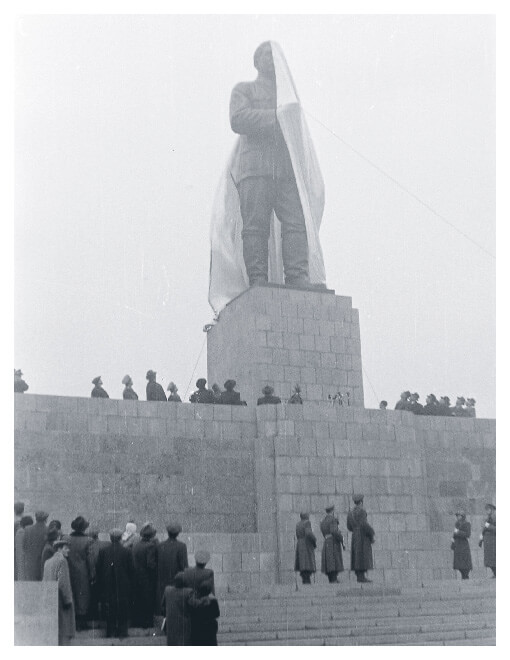

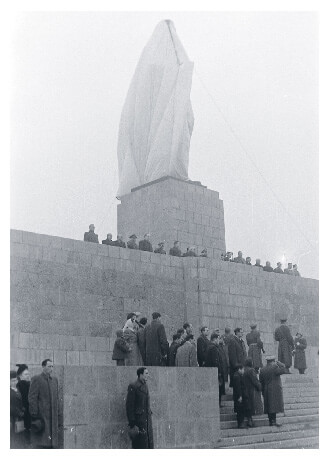

Rákosi promoted the five-year plan everywhere he went.

“LIVING STANDARDS

ARE GOING UP”

“COMMUNISM IS BRINGING

BOUNTY FOR ALL”

“HUNGARY IS BECOMING

A RICH SOCIETY”

His recorded speeches droned on and on over the radio and public sound systems all across Hungary, as if rhetorical repetition would compel Hungarians to believe the planned economy was a smashing success.

But all evidence in their daily lives proved the opposite. Short training courses left newcomers ill-equipped for their new jobs. Established workers, resentful of the increased competition, undermined the “new working class.” Men rebuffed the women workers. And all workers, who were being paid by the piece rather than an hourly wage, were cheating (and being cheated) everywhere. Meanwhile, authorities constantly ratcheted up output goals towards an untenable 142% of initial targets. Living standards everywhere decreased.

Rákosi’s industrial plan was such a social and economic disaster that the state began sending prisoners to mines and construction sites in 1951 as hundreds of embittered, displaced former farmers walked off the job. The prisoners created another source of tension at the industrial worksite: free vs. forced labor.

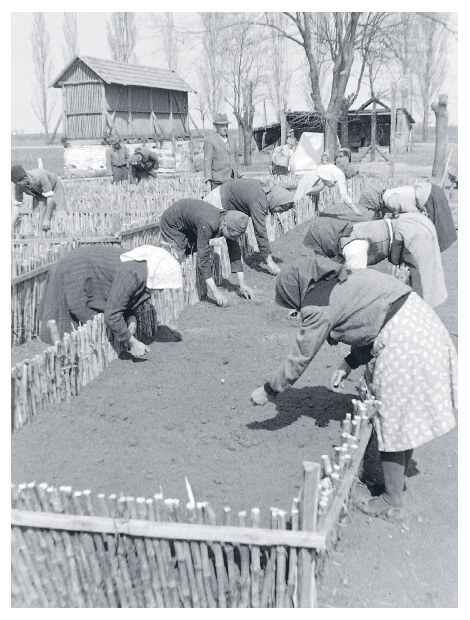

THERákosi dicatorship’s planned economy was perhaps going even worse in the countryside. Most farmers simply did not want collectivized, industrial-scale farming practices imposed on them from on high. They were proud of their privately-owned land, farming techniques, and traditions. They were particularly resistant to state requisitioning of their animals and hard-earned assets.

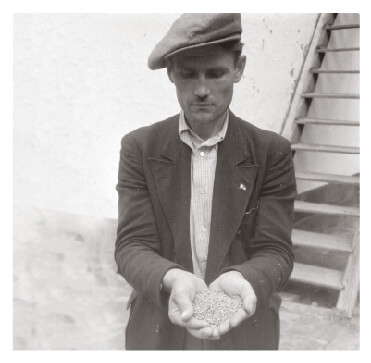

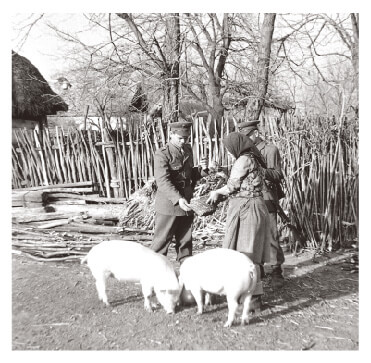

Outwitting the state collectors became a way of life. Peasants got their pigs drunk on wine or brandy to make them look diseased, secretly slaughtered their animals at night, and developed networks to warn other families when the collectors were coming. They evaded compulsory quotas by diluting their milk, hiding their grain, and bribing officials. They did everything they could to undermine the new system and keep the fruits of their own labor. Still, many got caught.

Meanwhile, life on most collective and state farms failed to deliver the great bounty through modern efficient farming that communist ideologues had promised. Workers were disorganized and often lacked proper equipment. Members were paid only every six months (and then never enough) so there was little incentive to work hard. Like the industrial workers who had been promised higher wages and better living standards, many collective farm workers felt duped.

“I CAN’T EVEN BUY

A PACK OF CIGARETTES!”

- COLLECTIVE FARMER, 1951

Morale dropped in the countryside. Agricultural output dwindled. Those most experienced at handling larger farms (like my grandfather) were serving prison terms or doing forced labor, or had fled to the cities. Not surprisingly, food supplies to urban centers declined precipitously!

SOthe Rákosi dictatorship, in a panic, began subjecting collective farmers to the same extraordinary taxation, coercion, and police supervision as independent farmers.

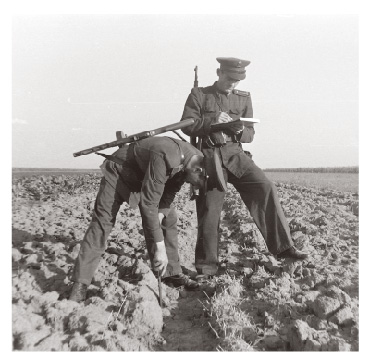

Often working in pairs, state police in the localities:

They brought terror to the countryside. The Rákosi era also introduced some advancements to Hungary: rural electrification, radio, and some updates in agricultural and industrial technology. But generally speaking, the 1950s were a difficult time for Hungarians.

“THE SOMOGY COUNTY

PROPERTY COMMISSION

[TRANSFERS] THE FARM OF

ISTVÁN FÁBOS AND

HIS WIFE GIZELLA VAJDA,

CHILD ARANKA FÁBOS

AND CHILD GYULA FÁBOS

...TO THE HUNGARIAN

STATE TREASURY.”

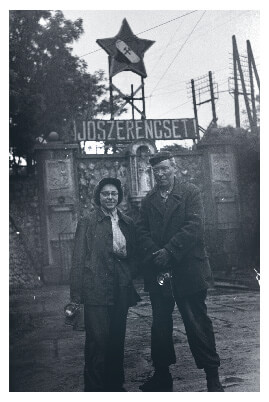

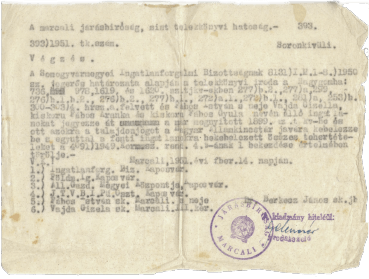

PISTAwas finally released from hard labor in the quarry at the end of 1951. He had been imprisoned for nearly two years. Almost as soon as he arrived home, Marcali’s communist authorities issued this paper from the Land Registration Office that documents the official transfer of Fábos family property— this time including the family’s entire house—to the state.

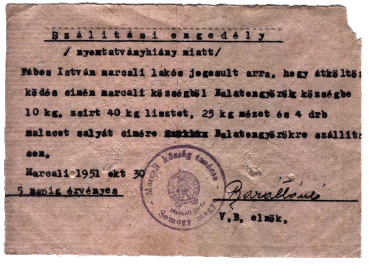

The Fáboses had to leave their house, their farm, their belongings, their land, nearly everything. Here is the family’s official travel permit that listed the very few provisions they could take from the farm.

“MARCALI RESIDENT ISTVÁN FÁBOS

IS ALLOWED TO TRANSPORT:

10 KG OF LARD,

40 KG OF FLOUR,

25 KG OF HONEY

AND 4 PIGLETS

TO HIS NEW ADDRESS IN

BALATONGYÖRÖK DUE TO MOVING."

MARCALI,

OCTOBER 30, 1951

VALID FOR 5 DAYS

Somehow they were able to secure jobs on a state farm in Balatongyörök, on the other side of Lake Balaton.

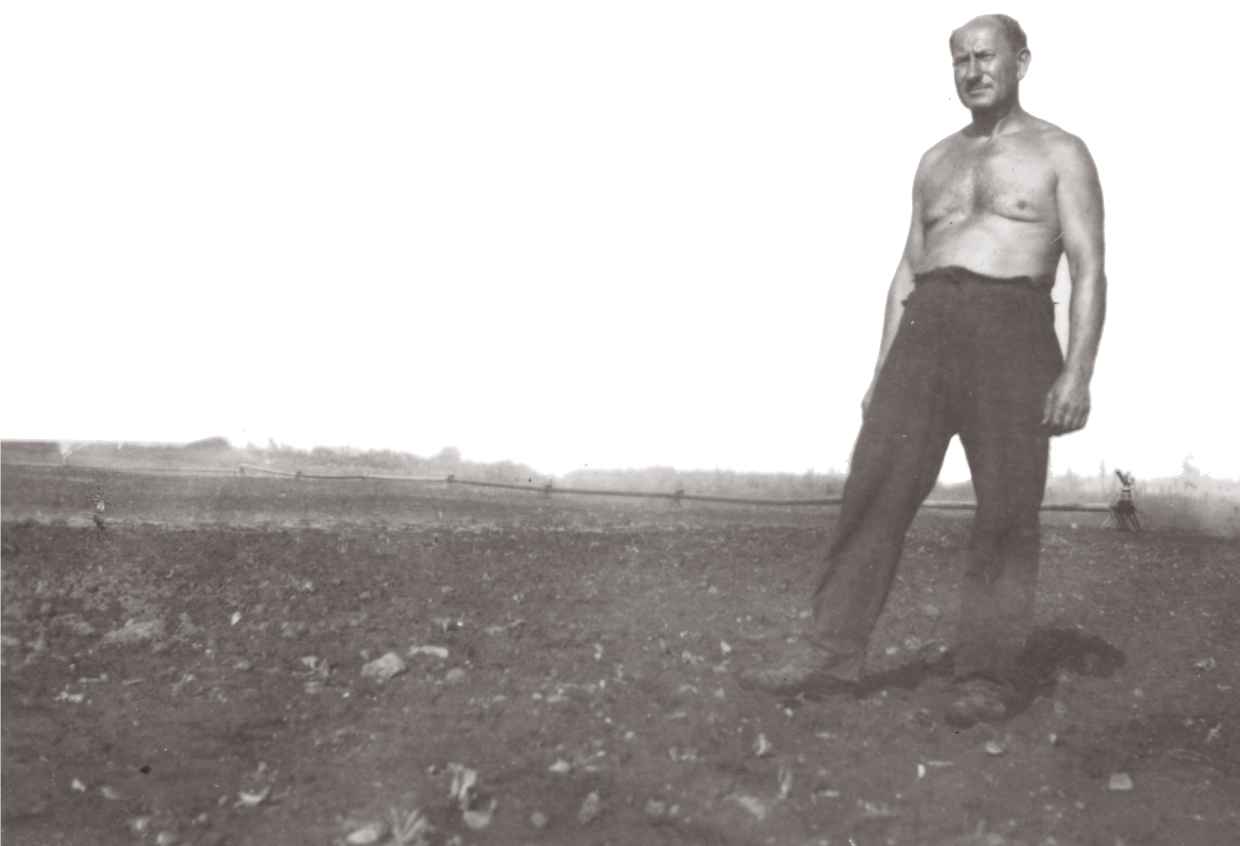

There, Pista became responsible for the irrigation of hundreds of acres of vegetables.

My grandmother Gizi, who had a weak heart and had fallen into a deep depression after all the stress of the past two years, maintained a household with what little they had.

Gyula, now 19, recorded the weights of the state farm’s many cattle...

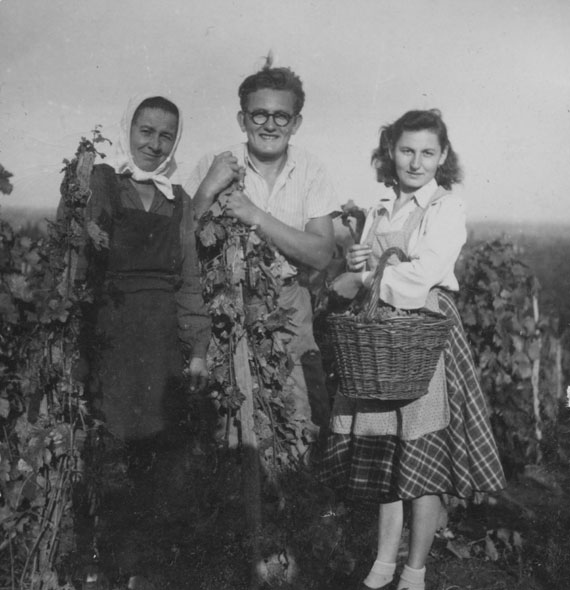

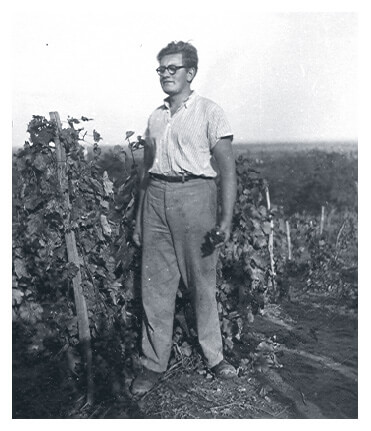

…but soon found a better job at another state farm farther up on Balaton’s northern shore (in Balatonakali), overseeing the development of an almost 700-acre (280-hectare) vineyard and 100-acre almond grove.

He lived with other farm managers in the Pántlika Castle, once the home of Benedictine monks.

In Balatonakali, Gyula was impressed by the farm’s enormous, industrial-sized steam engines, combines, and plows that could loosen soil to the depth of an impressive twenty-eight inches—all examples of a new modern era of Hungarian agricultural production.

Gyula was devastated to lose his family’s farm, yet he found a way to excel under the communist system. Many state farms were dismal failures, but Gyula proudly recalls that under his management, his state farm had a 97 percent success rate and even got a state medal for high productivity. He dated one of the women who oversaw the women workers. He swam in Lake Balaton with his friends after work was done. He had to keep his kulak past a secret (only his two supervisors knew, and took a risk in hiring him), but he found delight and validation on this state farm.

Ari, now 20, went back to her charcoal and brushes in Budapest. Her school merged with two others and was stripped of its Catholic designation. It was now a state institution, run by communist authorities.

The basic character of Marcali—an agricultural hub—changed, too, with the construction of two military bases beginning in 1951. The first base dominated the center of town. The second one was constructed next to the Széchényi Castle. Suddenly hundreds of soldiers from poor families flooded the town, changing its social composition.

Following the Stalinist roadmap, Rákosi and his regime uprooted my family and hundreds of thousands of other families across the Hungarian countryside.

This was Hungary in the early 1950s, in service to the Soviet Union, dismantling its past, and building an uncertain new future.