DURINGWorld War II, the Munkaszolgálat was the labor service required of all young Jewish men and other “political unreliables,” many of whom were abused to such an extent they did not survive the war.

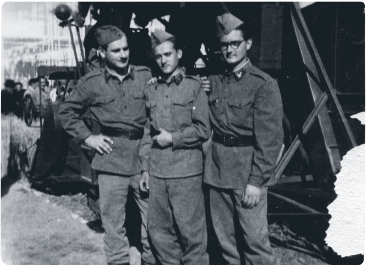

Now the Munkaszolgálat was made up of a new group of political unreliables like my father, the son of a former kulak. Gyula’s first task, along with a thousand other young men, was to build a military school near Budapest.

But on March 5, 1953, three days after Gyula arrived at the training camp, Stalin died.

STALINwas old but his death still came as a surprise. He hadn’t left a successor, and people wondered what would happen next: Who would replace Stalin? Would the Soviets leave Eastern Europe? Could this mean the end of communism? Would the wrongful imprisonment, forced labor, vicious purges, and everyday terror come to an end?

With their heads newly shaven, Gyula and his fellow recruits stood out in the cold without their hats to publicly mourn Stalin’s death. They were freezing but happy inside, thinking the communist system might crumble.

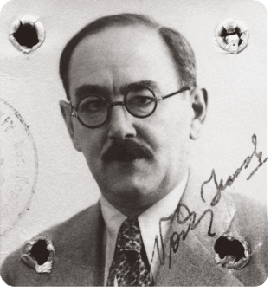

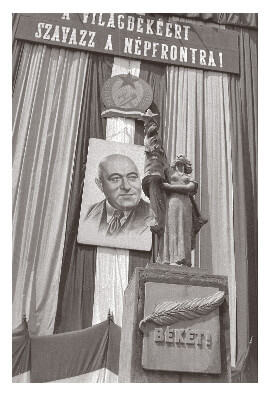

It seemed logical that Hungary’s own “Little Stalin,” Mátyás Rákosi, would have to abandon his ruthless policies.

But that’s not exactly what happened. Rákosi stayed the Stalinist course and kept up the terror campaigns. Meanwhile, his economic policies pushed Hungary’s economy towards the brink of collapse.

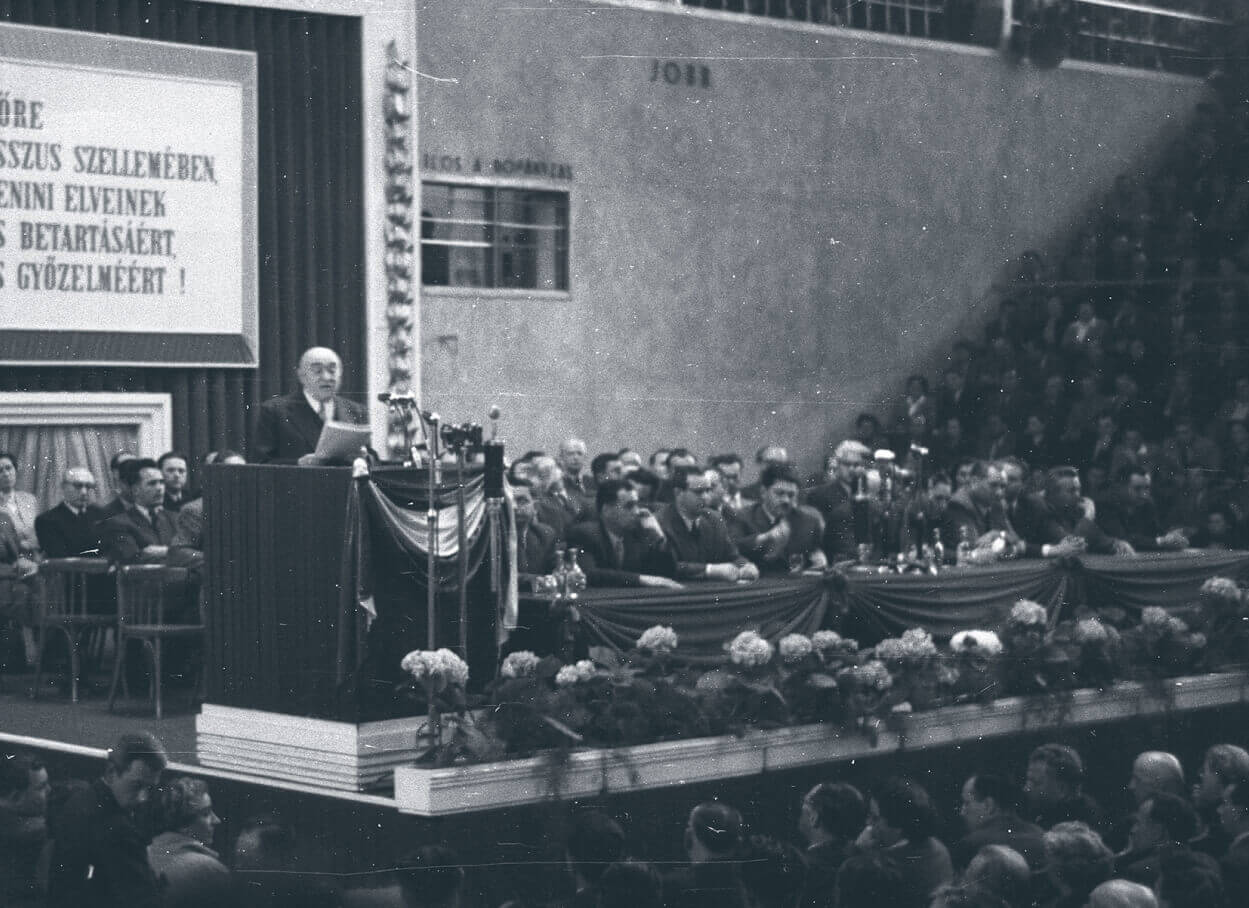

By June 1953, officials in the Soviet Union were finally fed up with Hungary’s dysfunction. They summoned Rákosi to Moscow, demoted him to General Secretary, and appointed the more liberal Imre Nagy as the new Prime Minister. The bald murderer, used to getting his way, had fallen from grace. (He was surely seething.)

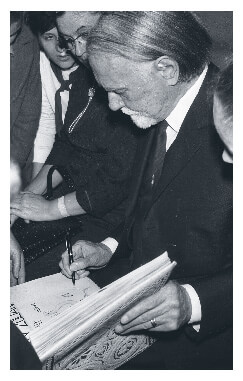

Nagy had grown up poor near Marcali. His father had been a manorial servant and his mother had been a maid. He followed a typical route to Communist Party leadership. As a Hungarian soldier in World War I, Nagy was held prisoner in Russia, where he became inspired by communist rhetoric. Later on, he held a minor post in Béla Kun’s short-lived Soviet Hungarian Republic and escaped Horthy’s White Terror in the early 1920s by laying low. He worked for the Soviet Union during World War II, and, in the coalition government of 1945, he was named Hungary’s new Minister of Agriculture.

WHATfollowed Nagy's appointment to Prime Minister was a period of experimentation. Nagy was the face of a more open, humane Hungarian Communist Party. He immediately instituted a number of reforms:

- He allowed peasants to abandon state collectives and cooperatives and return to private farming.

- He loosened the state’s control over the media.

- He called for open discussions on political and economic reforms.

- He released 748,000 political prisoners.

- He ordered the regime’s police to stop surveillance on some 4,500 people.

- He even talked about free elections.

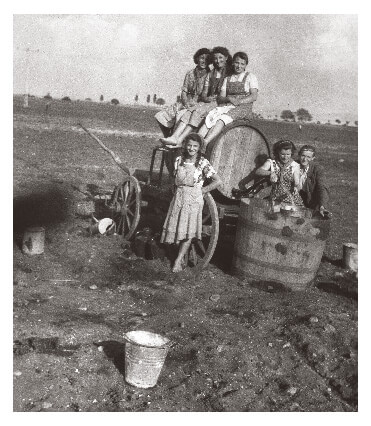

As life loosened up under Nagy’s leadership, Gyula’s experience in the Munkaszolgálat was not as bad as he feared. In fact, the construction work turned out to be quite fun.

Gyula and his fellow laborers found pleasure in undermining the communist system. They ripped and peed on cement bags to make them useless, cracked up bricks, made intentional messes, and installed subfloors that were only three centimeters thick instead of the required 10 centimeters. They also worked really slowly. This was exactly the kind of resistance Gyula’s ancestor, János (my great-great-great grandfather), likely used as a weapon while working as a serf within the oppressive feudal system.

1954

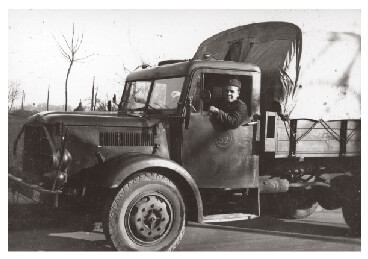

AFTERa year of construction work, Gyula’s supervisors reassigned him as a food truck driver. He also served meals to military officers and witnessed the indulgences of a new class of communist elite. Local functionaries and higher-ranking Party members often made huge messes at the table (because they could), and Gyula had to clean it all up.

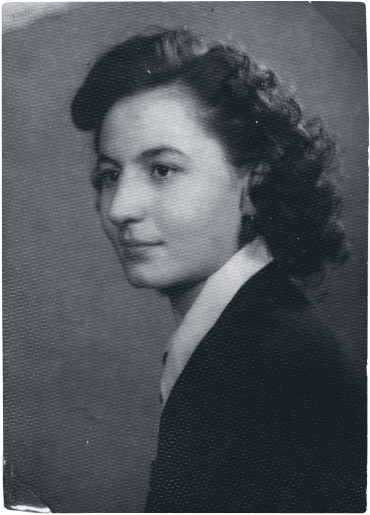

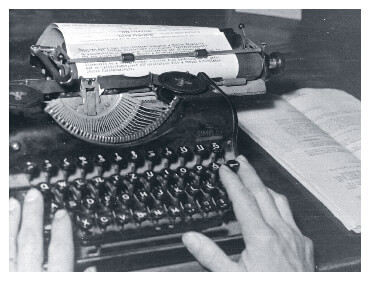

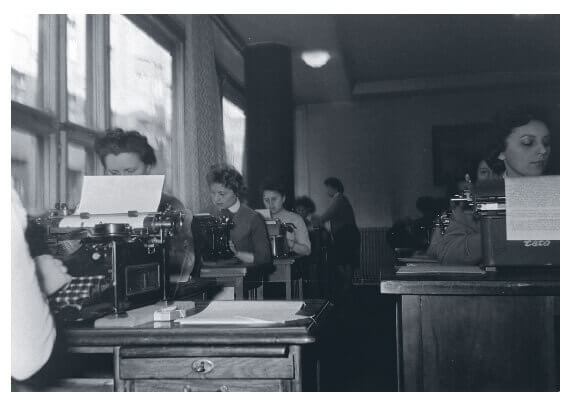

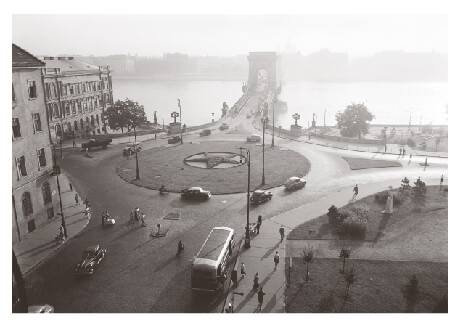

Meanwhile, Ari graduated and got a job in Budapest, typing addresses for the state’s health insurance bureau, SZTK.

But soon she moved up to the Department of Family Allowance (3rd floor), and then to the Department of Disability (5th floor), and finally to the Department of Retirement (8th floor), where she became an accountant.

She yearned to work with art, but she didn’t mind her job. In fact, one of the ironies of Ari’s situation was that while communism undermined her family’s livelihood, destroying her father’s and brother’s aspirations as landowners and upending their status as some of the most important people in society, communism opened doors for young Ari.

Her work life in Budapest was a game changer. She didn’t have to be a farmer’s wife. She didn’t have to live by such aggressively patriarchal standards. She could actually learn new skills and feel valued in the workplace. Communism had given her these opportunities.

Ari also became a black market watch dealer. It was Gyula’s idea. He visited Ari on his days off from labor service and brought her watches to sell to other SZTK employees. What a racket! Soviet soldiers stole the watches from Hungarians. Gyula and Ari bought them and then sold them back to Hungarians for a small profit. A capitalist black market was alive and well in communist Hungary.

Can you see the hypocrisy? The Soviet Army was supposed to be the ideological force that taught people how to be “ideal socialists.” They were supposed to represent a more advanced form of socialism.

If communism was the end game — a classless, moneyless, possession-less society — then the Soviet Union was supposed to be further along this continuum than the Soviet bloc countries, and Hungarians were meant to follow the Soviet Union’s example.

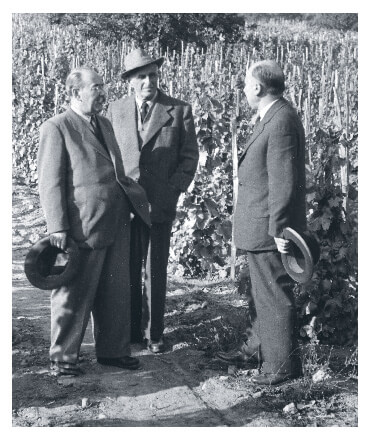

THE“New Course” reforms established by Imre Nagy lightened Hungarians’ moods and made life more bearable.

The music must have helped too. Kodály had chosen to stay in Hungary (while his friend, Béla Bartók, had reluctantly emigrated to New York in 1940 to escape the fascists).

The famous composer preached “music for everyone” (a rhetoric that appealed to communists) and established hundreds of musical primary schools, workers’ choirs, and choir festivals. Since his pedagogy involved Hungarian folk songs, Hungarians all over were able to both sing their hearts out and voice a kind of national pride.

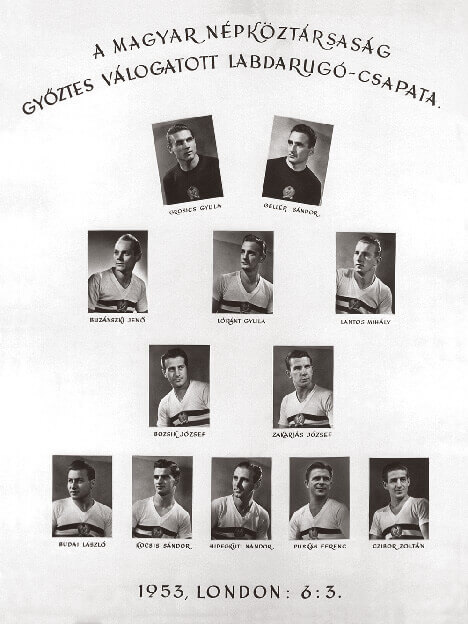

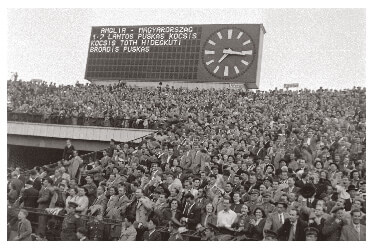

ON the field, Hungary’s Golden Team, the most talented national soccer team in Hungarian history, was on an astonishing winning streak. Also referred to as the "Mighty Magyars,” the squad had won Olympic gold in 1952 and became an even bigger international sensation in 1953 after defeating England 6-3 in front of 105,000 people in Wembley Stadium.

Three weeks before the World Cup in June, 1954, the Golden Team thrashed England again (7-1), this time in Budapest.

The world followed on television (a first in World Cup history) as the Hungarians flawlessly advanced to the World Cup finals and became the clear favorite to win against West Germany.

The final match against the Germans was played in pouring rain, and the Hungarians did well until the West Germans brought out their secret weapon — new Adidas shoes with screw-in studs — and squeaked through a victory.

When the game was over, thousands of Hungarians spilled into the streets. They were crushed, but also angry. Rumors flew that the team and Party leaders threw the match in exchange for 50 Mercedes cars. And sure enough, Mercedes began appearing in Hungary for the first time, with Party leaders inside them....

This series of events, combined with Imre Nagy’s more humane New Course, encouraged Hungarians to experiment with public expressions of anger. They began marching in the streets.

1955

WITHthese emboldened protests, the Soviet Politburo once again looked at Mátyás Rákosi more favorably, forgetting why they had ever instated Imre Nagy in the first place. They told him (and his proxy, András Hegedüs, another Stalinist hardliner) to restore order in Hungary. And so, in a shocking reversal, the Soviet Politburo ousted Nagy less than two years after appointing him Prime Minister. Rákosi, of course, wasted no time reintroducing his old tactics.

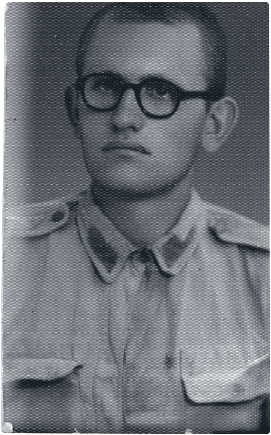

The dictator’s return to power had huge ramifications for Hungary, and also for Gyula, who was just finishing up his two-year commitment in the Munkaszolgálat. He still faced sabotage charges (which he inherited from his father) and had successfully delayed his trial with the help of a family lawyer. But with Rákosi and his people back in power, and with a new crackdown on their agenda, Gyula was targeted by the regime.

IN1955, the secret police (ÁVH) suddenly arrested Gyula and took him to a military jail in Budapest. They tortured him with sleep deprivation and shone bright lights into his eyes while forcing him to keep them open. They interrogated him endlessly.

"DID YOU SPY FOR

THE UNITED STATES?”

“DID YOU STEAL FOOD

WHILE DELIVERING IT

TO YOUR CAMP?”

Of course, his crime was that he had been a “kulak.” It was so scary. It was as if Rákosi himself was in the room. At Gyula’s trial, Ari sat directly behind her brother.

Just as Ari had protected Gyula from bullies growing up, and had helped him through his first torture ordeal in Marcali, she was again by his side.

Communist authorities sentenced Gyula to two years of hard labor and kept him in the Budapest jail for three months (although at the time he didn’t know how long he’d be there).

The cell, which was built for five men, held 25. The iron bunk beds were stacked three levels high with two men in each bed. The only solid food the prisoners got was 200 grams of dry bread each morning, along with starvation portions of thin bean soup.

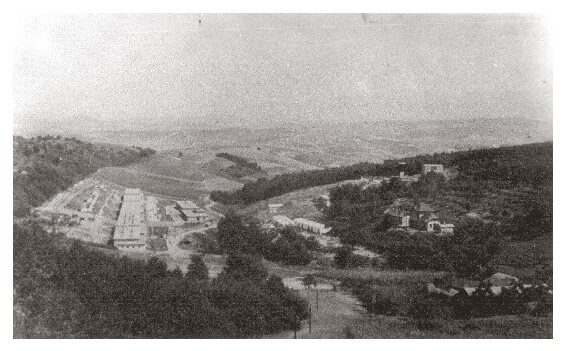

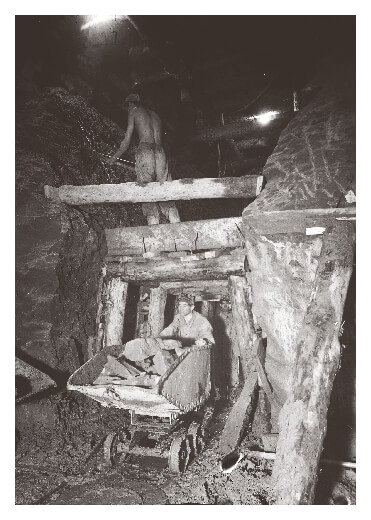

By mid-April, guards transferred Gyula to the coal mining region in northern Hungary not far from the Czechoslovak border. They gave him a striped prison outfit and assigned him to one of five large barracks, each holding 200 men, either common criminals, political prisoners like himself, or Jehovah’s Witnesses.

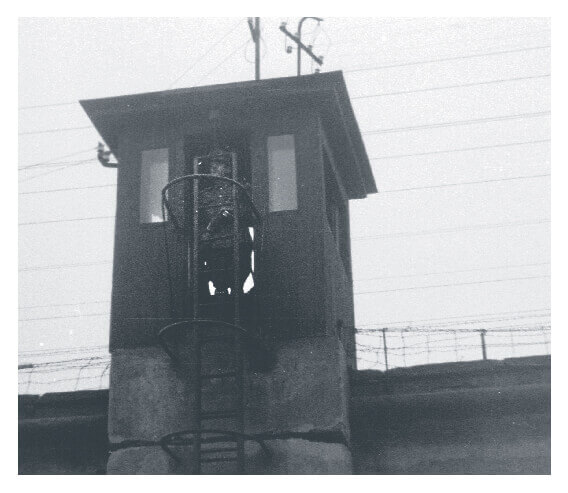

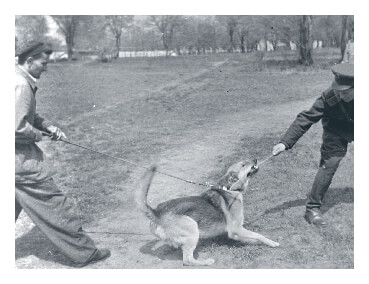

This place, the Tólápa mine, was pretty close to hell. Guards marched everywhere with vicious German Shepherds. The watch towers were lit all night long. The outhouse was infested with large rats.

Working several hundred meters underground, the prisoners were drenched in sweat and then forced to wait at the top of the mine, often in freezing conditions, while authorities assembled all prisoners to return to the barracks.

By pretending to be extra clumsy, Gyula convinced guards to reassign him above ground. The best job was planting bushes. The worst was repairing fences during a bitter cold winter with no gloves.

These years were full of uncertainty for Hungarians and for the Fábos family. Each pendulum swing between liberalization and repression brought hope followed by despair. Such emotions would only heighten in 1956.